Witness deciphers sounds from 911 call

Was a Hayden man fleeing for his life or attacking a family when he was shot at and allegedly murdered an Athol woman on New Year’s Day?

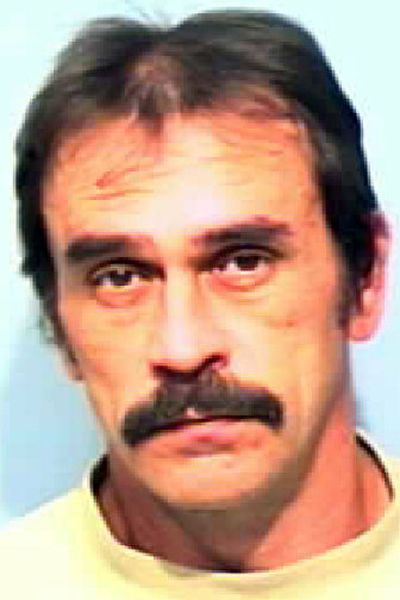

That was the focus of Friday’s testimony in the trial of Jonathan Wade Ellington, who is charged with second-degree murder and two counts of aggravated battery for allegedly running over Vonette Larsen and ramming a car with her two daughters in it.

Eric Hartmann, an audio engineer from Arizona, testified that he discerned five separate sounds similar to gunfire on the 911 call made by Vonette Larsen’s daughter, Joleen. He said all of the sounds came after Ellington allegedly began to ram the Honda Accord that sisters Joleen and Jovon Larsen were in with his Chevy Blazer.

The evidence is crucial to Kootenai County Deputy Prosecutor Art Verharen’s case. Verharen contends that Ellington deliberately rammed the car and hit 41-year-old Vonette Larsen with his vehicle. He says Ellington was fired on while he attacked the family, not that he was fleeing for his life while being shot at.

Defense attorneys revealed in court Friday that the incident also sparked a $1 million lawsuit by the Larsens, who contend that a sheriff’s deputy “abandoned” the young women and their parents and left them “at the mercy of Jonathan Ellington and his erratic and dangerous behavior.”

During testimony, Hartmann, who worked in audio and video forensics at Rocky Mountain Information Network in Phoenix, said he found five “percussive incidents” that were consistent with gunfire after he enhanced a digital version of the 911 call made by Joleen Larsen during the incident.

The testimony came after Hartmann had already given his statement in court without the jury present because Ellington’s defense team argued Hartmann’s work was unscientific, and he is not an expert in his field.

Judge John Luster admitted the testimony and jurors heard Hartmann’s opinion on the alleged gunshot sounds. Defense attorneys, however, moved for a mistrial – the fourth time since the trial began – because Verharen elicited an answer from the witness that defense attorneys believed was intended to get sympathy from jurors.

Hartmann worked with the Rocky Mountain Information Network for just two months this year, and Verharen asked why that was. Hartmann replied that the Ellington case, and his work on the 911 tape of the incident, made it so he could not sleep at night. Before he could respond further, defense attorney Chris Schwartz objected.

“This amounts to prosecutorial misconduct,” Schwartz said. “It is irrelevant … and designed to remind the jury how awful this case is.”

Luster agreed with Schwartz that the testimony was unnecessary and that even though there are some “aspects of this case that are particularly disturbing … this case needs to be tried on the facts.”

The judge again denied the mistrial motion but warned the prosecution that he was “starting to become a little bit concerned” with the way the prosecution was “focusing on emotional details.”