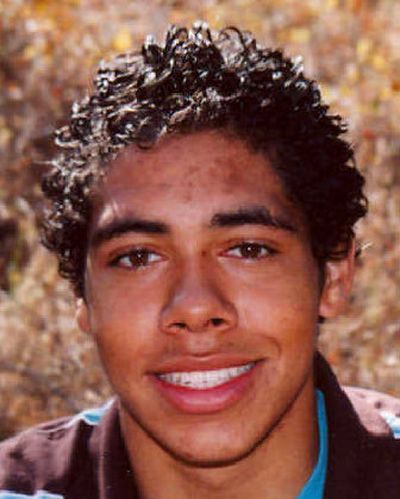

Young Malmoe knew how to live

The saying Devin Malmoe penned onto his bedroom mirror was “live life like it was your last day.” Now nobody utters the phrase without shaking their head.

“He was a good kid and he touched everybody’s heart,” said Devin’s mother, Bridgett Malmoe.

If you knew Devin, you had to expect that at some point you were going have to tell his story, just maybe not this soon. He was the popular boy with fashion-model looks who stuck up for the awkward girl, the kid who ran with every clique. When the University High School honor roll ran in the newspaper, more often than not Devin’s name was on it. When he didn’t make the list, he’d just laugh and say, “Ah, it’s too easy”; he had other pursuits.

Devin died Dec. 9 in a head-on collision between two semitrucks on a narrow stretch of Highway 97 five miles north of Klamath Falls, Ore. The Spokane Valley 18-year-old had been moving furniture cross-country since graduating from high school last spring. He worked for Bridgett Malmoe’s ex-husband Lewis Purcell Jr. The two were returning home from Northern California in a Bekins moving truck when, for an unknown reason, an oncoming semi drifted into their lane. The twisted metal of the two rigs burned so hot would-be rescuers couldn’t approach the wreck for 45 minutes.

The trip was going to be one of their last because, at his mother’s insistence, Devin had just finished the admissions paperwork for Eastern Washington University. In her son, Bridgett Malmoe saw the potential for a real “rags to riches” story.

Devin and his sister, Sheia Malmoe, grew up poor, raised by a beautician mother who, by her own admission, never seemed able to live beyond her next paycheck. They were the poorest kids in day care, the poorest kids in soccer league, the poorest kids in the classroom, kindergarten through high school.

Bridgett Malmoe, a single mother during part of her childrens’ upbringing, did her best to hide their meager income. She could sift through a Bon Marche clearance table for discount clothing like a prospector panning for gold.

“Devin didn’t know we were poor,” Malmoe said. “When I used to drop off my kids at day care, the teachers used to say ‘your kids are the best-dressed kids,’ better than the doctor’s and lawyer’s kids.”

Those nice clothes enforced the two messages Devin’s mother so desperately wanted him to believe: that he could be anything that he wanted, and that he was no less a person than anybody else. Her only other message was that his shirts always had to have a collar.

“I always dressed Devin with a collar because my kids are mulatto,” said Malmoe, who like 94 percent of Spokane Valley, is white.

It shouldn’t have mattered that the color of Devin’s skin matched only 1 percent of the city’s residents in the last U.S. census, but unfortunately, Bridgett said, for some people it did. She wanted to make sure that in a crowd her son looked a little more put together than the next child.

Devin was more put together, said Vicki Sutherland, whose children had been friends with Devin since kindergarten.

“He was always styling,” Sutherland said. “He just had this confidence. He could wear anything and get away with it.”

Sutherland remembers taking Devin and her son, Cody, to Mirabeau Park last fall for senior pictures. Cody brought one set of clothes, but Devin brought a wardrobe – four or five pairs of pants and 10 or 15 shirts – and wound up with eight different fashion ensembles.

She didn’t mind. It’s just a fact of motherhood that other people’s children, if they hang in your house long enough, will get on your nerves, Sutherland said, but somehow Devin never did. He’d flash his smile and any tension in the air just melted like butter.

Devin didn’t like conflict. He was a peacemaker who went out of his way to get everyone involved.

He didn’t wrestle, but when his school’s grapplers met their crosstown rivals for bragging rights, Devin resurrected a one-piece wrestling suit he hadn’t worn since fifth grade and paced the sideline to incite the crowd.

He didn’t want to disappoint his mother, so when Devin thought he’d crossed a line, he’d ease into truth in the most disarming ways, like last Thanksgiving when he arrived at the airport with a long knitted stocking cap pulled down past his ears.

Devin got his mother in the car and her luggage in the trunk, then rolled up the edges of his cap to reveal he’d gotten his ears pierced over the break. After the shock wave passed through the car, he disclosed that his sister was with him when he did it and that they had thrown a party at Bridgett’s house, but had cleaned it all up. No harm, no foul, except for a few wine bottles from Bridgett’s wine rack, which Devin was too young to replace.

“When he caved in, he killed you with kindness,” said Devin’s father, Shelby Nichols IV.

Nichols wasn’t around much when Devin was growing up.

It was Purcell who filled the role of father. Friends described the stepfather and son as polar opposites, easygoing Devin and Purcell, who was hard-driven and often valued his opinion more than getting along. The two were a team.

Since Devin was 11, he and Purcell had crisscrossed the country in Bekins rigs packing and unpacking new beginnings for strangers. They’d been to Mardi Gras in New Orleans and the beaches of the Florida Keys.

They might have been working on Dec. 9, but undoubtedly they were living life like it wouldn’t matter if they didn’t see the 10th.