Halftime show full-time work

Seven hundred and twenty seconds.

That’s what it comes down to – 12 minutes.

The Super Bowl halftime show, the world’s most-watched annual music event, involves millions of dollars, thousands of people and 15 months of preparation.

And it lasts 12 minutes.

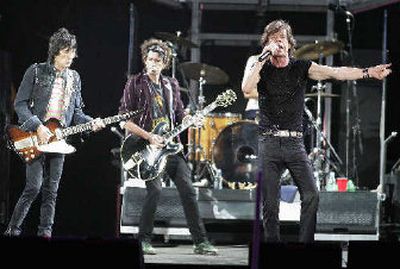

That figure doesn’t come with any give-or-take this-or-that. Talk to the professionals behind Sunday’s halftime show featuring the Rolling Stones, and you discover new definitions for words like “precision” and “rigor.”

“There won’t be a frame of video that we haven’t pored over and discussed thoroughly beforehand,” says Bob Toms, senior producer of ABC Sports, which is broadcasting this weekend’s Ford Field festivities. “It’s the culmination of a whole lot of work.”

Don Mischer, executive producer for Super Bowl XL entertainment, whose resume includes three Super Bowls and a Summer Olympics opening ceremony, says his task is even tougher this year.

Unlike every other performer Sunday – and virtually every Super Bowl performer of the past decade – the Rolling Stones won’t be playing along with the safety net of a taped track. They will be “live, live, live,” as one NFL executive stressed – and stressed is what it leaves Mischer.

“With Paul McCartney last year in Jacksonville, the decisions had all been made early, he’d rehearsed it many, many times, and as a result it was a very clean kind of coverage,” Mischer says.

“Here it’s a very different kind of group. You don’t necessarily know what they’re going to do. There’s more moving around, more raw energy, more unpredictability. There’s no question that’s going to make my job more difficult.”

To the delight of Super Bowl organizers, the Stones have proved to be masters of keeping secrets. The band is tightly guarding its set list, and was still mulling over song possibilities this week, Mischer says.

“The options are wide open,” he says. “Decisions could be made up to the very last minute in terms of what the Stones do.”

Charles Coplin, the NFL’s vice president of programming, says the league likes to view the relationship with its performers as a partnership – an alliance in which each party reaps big benefits from the other.

Which means that even if Mick Jagger and company would take directions from anybody, the NFL hasn’t been giving them.

“To come in telling them what or how to play isn’t something we would do,” says Coplin. “We make suggestions of what could resonate best with our fans. We talk it through with them, and most of us are fans of the music to begin with.”

The NFL and ABC do maintain veto power on the content of the performances – an area of particular sensitivity since Janet Jackson’s 2004 halftime bust.

“We’re in a position to say, ‘That’s not a song you should be playing,’ ” says Coplin. “We’ve done this with a lot of artists, so we know there’s a fine line between artistic expression and what’s appropriate.”

In the Super Bowl’s early days, entertainment was provided by such squeaky-clean performers as Bob Hope, Carol Channing and Up with People.

In 1967, while the Rolling Stones were busy producing an album called “Her Satanic Majesty’s Request,” the University of Arizona marching band handled musical duties for the pregame, National Anthem and halftime segments of the inaugural Super Bowl.

By 1992 the NFL realized it had a problem. An alternative halftime program offered by the upstart Fox network – frisky comedy skits from “In Living Color” – had lured millions of viewers away from CBS, where the Super Bowl and its Dorothy Hamill halftime were being aired.

Many didn’t click back, and Super Bowl XXVI finished with the game’s second-worst numbers in two decades.

A year later, Michael Jackson became the first modern superstar to headline halftime.

“The league had to respond to stay on course with what the audience wanted,” says ABC’s Toms. “You can’t forget that people are watching because of the quality of the game, and the rest of the telecast has to reflect that.”

Toms and other professionals describe the game-day rush as a mix of adrenaline and butterflies, one which transforms into a kind of Zen-like focus.

Jeff Crawford, on the other hand, isn’t sure what to expect. Unlike the show-biz veterans behind the scenes, the South Lyon, Mich., resident has never been to a Super Bowl, and with Sunday approaching, he’s simply pumped.

Crawford, 43, is among the local folks who signed on to take part in the halftime spectacle – extras in the Rolling Stones show, in a sense.

Their precise roles remain unclear; producers aren’t talking, and participants have been asked not to divulge details.

“For all of us, this is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to be part of something really special,” Crawford says.