Following A Dream

About four years ago, Tim Hunt had a dream; he saw long lines of trucks hauling equipment away from his factory at the Spokane Industrial Park.

After talking with his wife, Resa, Hunt said he interpreted the dream as a sign from God to move his large cabinet-making company out of the industrial park to a new location.

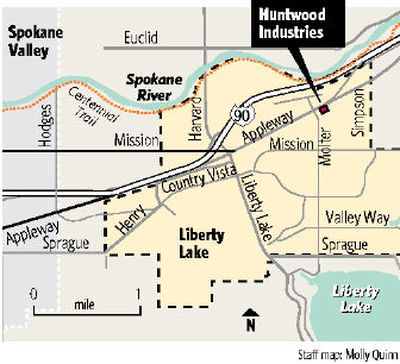

The dream unfortunately didn’t tell him where to move his company, Huntwood Industries. It took the Hunts another two years before they settled on 84 acres in Liberty Lake.

Last month, Huntwood Industries and its 620 workers moved into the mammoth manufacturing center. The building, equipped with high-tech production equipment, is the largest of its kind in the Western United States, said Tim Hunt, the company’s president, and Resa Hunt, its vice president.

The Lord may have guided the initial decision, but the Hunts also relied heavily on their experience running a large company and on research into the newest manufacturing technology.

The fast-growing, family-owned business is more than just Spokane’s largest manufacturing employer. Dick Titus, executive director of the Kitchen Cabinet Manufacturers Association trade group, said Huntwood is “a perfect example of how companies serve the market by adopting technology, improving productivity and broadening choices for customers.”

Like several other companies that Titus places among the nation’s highest-revenue cabinet makers, Huntwood’s business depends on providing a wide range of cabinets for kitchens, bathrooms, entertainment rooms and offices.

While Hunt won’t say what 2005 sales were, in 2004 the company racked up $67 million in sales, an increase of 20 percent from the year before, according to Wood and Wood Products magazine. Hunt said his company has seen double-digit growth each year since the late 1990s.

Showing off the interior of Huntwood’s vast assembly center, the 54-year-old Hunt said the price tag for the building and equipment comes to around $70 million.

“We have a healthy belief in the company and in the future of the cabinet making industry,” Hunt said of the investment the new building required.He won’t say how much he spent on new production technology inside the 556,000-square-foot building.

He knows it’s far more efficient than his old plant, but he won’t be able to gauge the exact gain in efficiency until the new systems have been fully tweaked and modified.

Here’s a hint, though: workers produced 1,100 cabinets a day in Huntwood’s two former assembly buildings at the industrial park. In the Liberty Lake plant, they’re producing 2,000 cabinets daily and eventually will hit 5,000 a day, he said.

He calls it the most environmentally friendly factory of its kind in the country.

Huntwood’s Liberty Lake plant uses state of the art equipment to reduce the fairly large volume of waste and emissions produced there, said April Westby, environmental engineer with the Spokane County Air Pollution Control Authority. At its former industrial park site, the company was releasing between 250 to 300 tons of paint fumes a year, she said. The new site’s thermal oxidizersare designed to reduce emissions significantly, she said.

The new building is also the only U.S. cabinet factory Hunt knows of using two robotic forklifts made by a Danish manufacturer. The machines are programmed to haul pallets of precut wood and finished products to and from work stations across the factory. Sensors placed in the aisles or along interior supports guide the machines from one spot to the next.

“The (robots) each cost about what you pay for a new vehicle,” Hunt said.

Other cutting-edge production equipment has come from companies in France, Italy and Germany.

He’s possessive of what he’s using, to the point of imposing a ban on photos of some of the equipment. Visitors are also screened to prevent competitors from scouting out his equipment.

That respect for innovation is part of his inherent entrepreneurial talent, said Resa, who married Tim when she was 18.

“He’s always been a good manager. He works well with people and he likes seeing things grow,” she said.

Except for a short two-year stint as a stockbroker in his 30s, Tim Hunt has worked all his life in the wood-products industry. He credits his grandfather, a miner in North Idaho, for his early exposure to the value of work.

Tim’s father, Charles Hunt, cut logs and sold the wood to North Idaho mining companies.

His father died in a car crash when Tim Hunt was 11. In his teens Hunt moved to Hillsboro, Ore., taking a minimum-wage factory job at Noble Craft, which then was the Northwest’s premier producer of quality cabinets.

“That was my first exposure to high-volume (cabinet) production,” Hunt said. “I learned the business ground floor up, doing grunt work and whatever was necessary.”

Resa Hunt, who’s 50, has a key role in the company. She focuses on product design and on long-term company strategy.

Tim and Resa often publicly state the importance of faith in how they view their roles as company owners.

“We feel the Lord has placed a blessing on this company and allowed us to have a vision for it,” Resa Hunt said.

She also said one valuable skill Tim developed — staying calm and never breaking off a business relationship out of anger — can be seen either as a Christian virtue, or just good sense.

Hunt himself places credit for Huntwood’s business growth — from 35 workers in 1988 to 620 today — to loyal employees and strong company managers who share his values.

“I’ve really learned that it’s to your advantage to go out and hire people who are smarter than you are,” he said.

He also believes in delegating responsibility for key decisions to the 40 to 50 company managers and department heads. “I try to empower them so they make their own decisions,” he said. “I want them to take a risk. That way they can always learn something if it doesn’t work out.”

Huntwood’s strong five-year growth has been driven by the robust and seemingly unquenchable U.S. housing market, said Titus of the Kitchen Cabinet Manufacturers Association.

The irony is that cabinet companies are doing well at the same time that nearly all other U.S. woods products companies are struggling with fierce competition, primarily from Asian producers, Titus said.

For reasons having to do with customer demand and speed of production, U.S. cabinet-makers have kept selling at a record pace, he said.

The market is lot like that for new cars: consumers want a wide variety of finishes, shapes, door styles and colors. And they don’t want to wait long for delivery, Titus said.

“Companies like Huntwood can produce cabinets in less time than it takes to have that product ordered and delivered from China,” he said.

About 95 percent of the company’s cabinets are sold west of the Mississippi River.

“We don’t plan to shift more attention (to the East Coast),” Hunt said. “There’s still a vast amount of business we can do out here, in the West.”

Titus and others say interest rates will rise in 2006 and dampen the new-home sales of cabinets. The upside is that remodeling hasn’t slowed down and remodelers account for about 70 percent of cabinet sales, according to the KCMA.

The size of the new Liberty Lake building shows that the Hunts are not thinking small. “We’re expecting steady growth for the next several years,” Tim Hunt said. “Our internal target is 20 percent per year.”

He said he and his wife have made a commitment to remain with the company until he’s 65 — 12 years away. Two of his four children now work within the company. So do two of Tim’s brothers; Dan Hunt is director of research and development, and Ted Hunt is director of dealer sales.

When Tim and Resa Hunt retire, direction of the company could include family members and other company managers, Hunt said.

One year ago, the family invested in a mining operation, becoming majority owners of the former Metaline Mining & Leasing Co. and changing its name to HuntMountain Resources.

Hunt is chairman of the mining company, which he said is part of an effort to diversify beyond wood products. HuntMountain has no mines and is primarily focused on exploring sites and looking for other companies to take on the mining operations.

The move to Liberty Lake nd his role in running a second company have turned his schedule into a blur, Hunt admits. The size of the company he runs also means more invitations to take part as a community leader — a role he hopes to assume later, when he has more time.

“I don’t want to volunteer for something I can’t devote time to. Right now, there’s really not much time for having a lot of fun,” Hunt said.