Retreat moves kids ahead

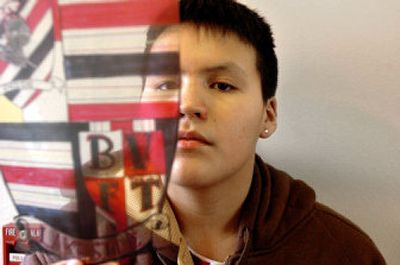

When these high schoolers heard the plan, they were skeptical – to say the least. Sinead Ambro, a sophomore: “I thought they was lying.” Vicki Sifford, a junior: “I thought they were crazy.” Ty Haverland, a junior: “I thought it wouldn’t work.”

The idea was to take Lakeside High School’s 150 teenagers – the entire student body for all four grades – to the Coeur d’Alene Casino for a day of ice-breakers, team activities and bonding.

Haverland assumed kids would run off or get in trouble. But no one did. Everyone listened to a speaker and participated in the activities.

And Ambro, Sifford and Haverland all attest to a change in the school since that October retreat, the brainchild of counselor Ginny Lathem.

The student body at Lakeside, which is located on the Coeur d’Alene Indian Reservation, is about 60 percent Native American and 40 percent white, with a handful of other minority kids. That makes it unique from most other schools in North Idaho, for which the majority are overwhelmingly white. That also presents unique challenges – and opportunities.

The students acknowledge a level of distrust about the “other,” passed down from their parents and other family members.

“Growing up, I heard a lot about white people. I’m not going to lie,” said Sam Harding, a senior.

But the younger generation is different, said Samuel Torpey, a sophomore. They’re realizing the need to come together.

That’s just what the students did at the retreat. They were randomly assigned to tables, with teachers and community members mixed in. They were charged with designing a shield, to go with the school’s knight mascot. In weeks following, the school voted on which of the designs would be emblazoned on things like T-shirts and letterheads.

Although the school is small and students see one another every day, it took an event like the retreat to encourage more interaction. The table assignments “helped us talk to someone we never talked to before,” Harding said.

For reasons no one could really put a finger on, these teens described a pre-retreat school atmosphere of indifference and devoid of school spirit.

“It’s like, no one wants to get to know each other,” Torpey said.

A wake-up call came in the fall when two students made threats against fellow students and teachers. They had a hit list, though they didn’t have guns on them at the time of their arrest. They were later expelled.

People thought they knew those guys, said Torpey. Students were shocked that something like that could happen at their school. “Everyone started realizing this is serious here,” Torpey said. “We should be learning one another, not just math or English.”

They’re getting there. The teens notice their schoolmates greeting and talking to people outside their usual circles of friends.

The retreat was a first step. A core group of Lakeside students – including those interviewed for this article – is exploring other ways to foster a better community and sense of unity at school.

“I want everyone to understand, when you walk in that door, you’re a Lakeside Knight,” said Lathem, the counselor. “It doesn’t take away from our individual stuff, it just connects us. It’s a common denominator. We are Knights.”