Senate is starting to check president’s power

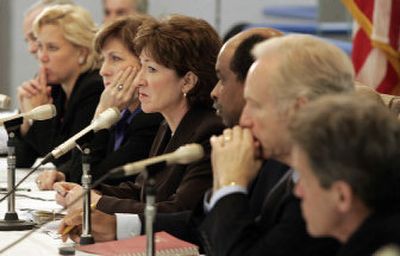

WASHINGTON – After years of deferring to the Bush White House, the Republican-controlled Senate has begun pushing back, holding oversight hearings on topics ranging from President Bush’s response to Hurricane Katrina to his administration’s mine-safety record and the president’s secret domestic-surveillance program.

Administration officials are fighting back.

An administration mine-safety official walked out of a Senate hearing last week, angering its powerful Republican chairman. The White House refused to give another Senate committee documents it sought about Katrina. The administration is trying to dismiss critics of its eavesdropping program as clueless partisans, though many of them are Republicans.

White House officials and their allies maintain that their stance protects inherent executive power. Critics say the administration’s reaction to the Senate’s inquiries is an assault on Congress’ constitutional role as a coequal branch of government.

“There is always a tension between Congress and the executive on information-sharing,” said Sen. Joseph Lieberman of Connecticut, a Democrat who’s generally friendly to Bush but has accused the White House of stonewalling over Katrina information.

“This administration, certainly among the three that I’ve served under,” he said, “is the most restrictive and protective about sharing information.”

The Bush administration has never been shy about testing the limits of its executive power. Vice President Dick Cheney refused to divulge the identities of energy executives who advised him on energy policy. The administration wouldn’t give Congress up-to-date cost estimates of its prescription-drug legislation. The Pentagon is often stingy about data on the war in Iraq.

The current clash is significant because, unlike during Bush’s first term, the Senate is demanding answers:

•A Senate Appropriations subcommittee had sharp words Monday for federal mining safety officials, blaming improper enforcement of regulations for the recent deaths of 14 miners in West Virginia. Two hours into the hearing, the acting head of the Mine Safety and Health Administration, David Dye, left despite requests from subcommittee Chairman Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., that he answer further questions.

•Federal agencies have refused to turn over documents about their communications with the White House related to Hurricane Katrina to two congressional committees that are investigating the federal response to the disaster.

•Specter has scheduled hearings for Feb. 6 on whether the president was legally permitted to authorize wiretaps in the United States without court warrants.

Such challenging examinations of the administration were virtually unheard-of during Bush’s first term.

Since then, Bush’s standing has plummeted. His response to Katrina, the continuing bad news from Iraq and other controversies have eroded his popularity.

In addition, with congressional elections in November, Republicans aren’t as concerned about advancing the president’s agenda as they are in advancing themselves. Both Republicans and Democrats have decided to resist Bush’s expansion of presidential authority.

Some, such as Specter and Sen. Susan Collins, R-Maine, now are leading inquiries into administration actions. Collins, who’s chairing the Katrina investigation, has objected to the White House’s refusal to turn over some documents and its instructions to agency officials not to reveal their communications with the White House about the hurricane.

“There are legitimate privileges that the president can cite,” she said. “But what is unacceptable for me is for the White House to tell officials in other agencies that they can’t even tell us who they called in the White House. That is a real stretch, and that is not a legitimate privilege that the White House has a right to exercise.”