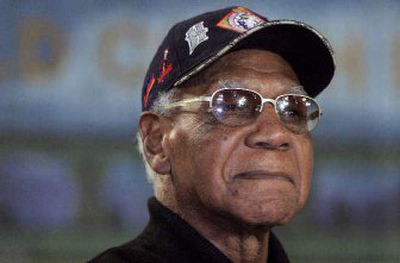

Buck isn’t bitter

By Sunday, there will be 35 individuals affiliated with the black baseball era enshrined in the baseball Hall of Fame. Buck O’Neil, generally considered the foremost ambassador and a living history of that bygone period, will not be among them.

For many who saw O’Neil play well over half a century ago and others who have since seen and listened to his passion for the game, that’s an injustice.

“I’m a big fan of Buck O’Neil,” baseball Commissioner Bud Selig wrote in an e-mail. “He is a charismatic figure who, throughout his life, has been a wonderful promoter of our great game. He is a true baseball legend.

“He should be in the Hall of Fame. As far as I’m concerned, he is a Hall of Famer.”

O’Neil had a 16-year career as a first baseman and manager with the Kansas City Monarchs, one of the Negro leagues’ storied franchises. He was a three-time All-Star and led the Negro American League in batting once, but his true measure probably came after his career with the Monarchs ended.

He became the first black coach in Major League Baseball, helped start the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Mo., and rarely has missed an opportunity to promote the game that has defined his life and that he has helped define.

“He has all of the qualifications. Professionally. Historically,” said Ulysses Hollimon, who grew up watching O’Neill play and later pitched against him while playing for the Birmingham Black Barons.

A special committee established to make a final selection of players from the Negro leagues and before in February chose 17 individuals to join the 18 who are already in the Hall. O’Neil did not make the cut.

As he has for most of his 94 years, John Jordan “Buck” O’Neil handled that disappointment without rancor.

“To me, whatever they do is going to be all right,” O’Neil said. “But to get into the Hall of Fame, that’s the top notch for every ballplayer. I was hoping that I got there, but the fact that I didn’t means that I shouldn’t be there.”

O’Neil will be at the induction ceremony Sunday in Cooperstown, N.Y., and will speak on behalf of the black baseball era and this year’s Hall of Fame class. None of the 17 being inducted are still alive.

“The thing about Buck is that he’s handled it easier than everybody else did,” said Jesse Rogers, a former outfielder and catcher with the Monarchs under O’Neil. “He’s been on committees and understands how those things work, so he’s not really too upset over it. He said for him to wake up every morning makes him a Hall of Famer.”

O’Neil said his only complaint was that the 12-person committee was made up only of Negro leagues historians and authors, no ex-players.

“None of the people on that committee ever saw me play,” said O’Neil, who played for the Monarchs from 1938 to 1955, spending his last eight seasons as a player/manager.

“They could have had players still alive, but they weren’t on there. That’s what gets me. … But that’s all right; I’m going to Cooperstown, and I’m going to represent the guys right.”

Things have not been going too well for the Kansas City Royals lately. They’re on pace to finish with more than 100 losses for the third consecutive year and will finish among the worst teams in the league in home attendance.

But on a recent hot, muggy Sunday afternoon, Kauffman Stadium was packed with excitement for a celebration of O’Neil and the Negro leagues.

“Buck is probably the best ambassador for not only the Kansas City Royals, but for the entire city of Kansas City, period,” said Billy Cutchlow, who was among a large crowd that stood in line for more than two hours to get an autograph and handshake from O’Neil before the game.

“Any event that he shows up, people are generally interested and supportive. There’s no doubt in my mind that he should be in the Hall of Fame. He has done more for the Negro baseball players than anyone.”

To many, O’Neil has been the face of Negro leagues baseball for decades. Known as one of the greatest historians and storytellers of the era, O’Neil’s celebrity status took off after he was featured in Ken Burns’ documentary “Baseball” in 1994. Last Tuesday, O’Neil became the oldest player to appear in a professional baseball game when he was intentionally walked to lead off the Northern League All-Star game in Kansas City, Kan. He had been signed by the Kansas City T-Bones, who then traded him before the bottom half of the inning.

O’Neil was walked again, but not without taking a swing that spun him around and nearly put him on the ground.

The T-Bones have been campaigning for O’Neil since the balloting was announced and say they have more than 10,000 signatures on petitions to have O’Neil enshrined.

“There have been plenty of people who have made commitments to the Negro leagues, but because of him being who he is, that’s why the history of the era is so popular now,” said Raymond Doswell, curator of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum. O’Neil, who is board chairman of the museum, was instrumental in getting it off the ground.

“He was able to not only tell the story, but tell the story well,” Doswell said. “He’s a former coach and a leader. He’s just been doing what he always does.”

O’Neil played an important role in earning pensions for former Negro leagues players and is a primary reason the Negro leagues museum has been such a huge success. He had proposed its creation for years before its founding in 1990, collected merchandise, drew attention to the cause and raised funds.

The museum has moved from a single office to a state-of-the art facility that has sparked a real estate revival around Kansas City’s historic 18th and Vine Street district.

“The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum is my pride and joy,” O’Neil said. “That’s the top of the line for my life.”