Carving a new niche

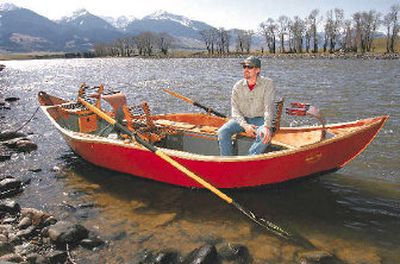

LIVINGSTON, Mont. — Jason Cajune calls it “the phenomenon.” Seconds earlier, as he towed one of his handcrafted wooden drift boats to a launch site on the Yellowstone River, he said, “Just watch, somebody will walk up and say, ‘Geez, I’d be afraid to use that boat,’ or, ‘I’d be afraid I’d scratch it.’ Everyone says that without fail.”

And, sure enough, an angler with two days of gray stubble and clad in baggy waders ambled up to inspect the boat and said as he shook his head, “Beautiful boat, but I’d be afraid I’d scratch it.”

Cajune turned and flashed an “I-told-you-so” smile.

It’s no wonder people feel skittish about scratching one of the boats created by Cajune’s crew at Montana Boatbuilders’ workshops south of Livingston. They are drop-dead gorgeous, undoubtedly some of the most beautiful boats on the market.

Seats, gunnels and dry boxes constructed of mahogany, ash and oak glisten under several coats of varnish like fine furniture that you wouldn’t dare subject to the rigors of water, rock and sandy-footed anglers.

Eventually, however, the owners of Cajune’s boats overcome their initial caution.

“You can make a lot of stuff that just looks pretty, but once they get out there and use them hard — like they’re really meant to be used — it’s just a tool,” he said. “Once people figure out the boats are pretty indestructible, they have few issues.”

Despite their handsome looks, Cajune’s boats are built stout.

The hull is constructed with marine-grade mahogany plywood overlaid with fiberglass and coated with marine epoxy. The bottom of the boat is made of a 3/4 -inch thick sheet of honeycombed polypropylene that is reinforced with Kevlar, the same stuff used in bulletproof vests.

As a final protection, a two-part abrasion-resistant polyurethane coating — similar to those used on pickup truck beds — is sprayed on the bottom.

“The boat looks pretty and delicate, but the guts of these boats are really tough and really high tech,” Cajune said.

Since Cajune’s boats are 100 to 150 pounds lighter than comparable fiberglass boats, they float higher in the water and miss many of the rocks other boats hit, he said. Because they float higher, the boats are also easier to row.

Montana Boatbuilders creates three main styles — the Freestone (in Classic or Guide styles), Freestone Skiff and Kingfisher (which also comes in the sexier and more popular Recurve style with curved gunwales). Prices vary depending on add-ons or upgrades, such as plastic seats instead of wooden ones.

Those looking to save cash can do all the assembly themselves with one of the kits the company offers.

A two-man kit boat is the least expensive model, priced at $1,500. The top end for kit boats is priced at $3,500 for a 16-footer. The kits arrive in a 4-foot by 8-foot crate, like a huge jigsaw puzzle.

Mike Hoiness, of Billings, bought a Freestone Skiff kit last February and had the finished boat launched by September.

“I’m real happy with it,” Hoiness said. “It’s a pretty fast boat, doesn’t draw much water. I used to have a big fiberglass boat that was kind of a tank compared to this.”

Growing up in the Flathead Valley, Cajune’s family ran the boat concession in Glacier National Park during the summer. It was there that he developed a love and understanding of wooden boats.

“They were all wooden boats from the ‘20s,” Cajune said. “So I spent every summer in Glacier Park since I was 8 or 9 years old. I started working on those boats and learned a fair amount about wooden boats.”

Cajune, now 34, also worked with a boat builder in Washington for six months and studied architecture at Montana State University. Ten years ago, he and his wife, Vedra, started Montana Boatbuilders in their Whitefish garage.

“Basically, we went down to the hardware store and bought a couple of clamps, scraped up $1,000 for wood and epoxy and built a boat,” Cajune said. “The first few years it was just her and I making sawdust.”

With the aid of a Web site, they sold their first boat.

“I don’t think we could have done this 20 years ago and been in business,” Cajune said. Now, 80 percent of his sales come from the Internet.

“We had the right product and were lucky enough to get it in the right spot so people could see it.”