Fastow breaks long silence

HOUSTON — Before Congress, he invoked the Fifth Amendment. He made no public statements. In court, he spoke few words other than his pleas — first not guilty, then a flip to guilty.

In the four years since the implosion of Enron Corp., Andrew Fastow has remained as quiet as prosecutors say he was vital to the accounting scandal that brought down the energy titan.

That changed Tuesday, when Fastow, the former chief financial officer of Enron, took the witness stand to testify against former bosses Kenneth Lay and Jeffrey Skilling at their federal fraud trial.

Silver-haired and articulate, Fastow explained to jurors a series of side deals and partnerships he struck to help the company keep its losses under wraps and boost its income.

“We were doing this to inflate our earnings, and I don’t think we wanted to show people what we were doing,” he testified.

He said the partnerships were blessed by Skilling, who was chief operating officer when the vehicles were first formed in 1999 and who Fastow said once told him regarding them: “Get me as much of that juice as you can.”

Fastow, 44, has already agreed to serve up to 10 years in prison after pleading guilty to two counts of conspiracy. The government can still prosecute him on 96 other charges if they are unsatisfied with his cooperation against his ex-bosses.

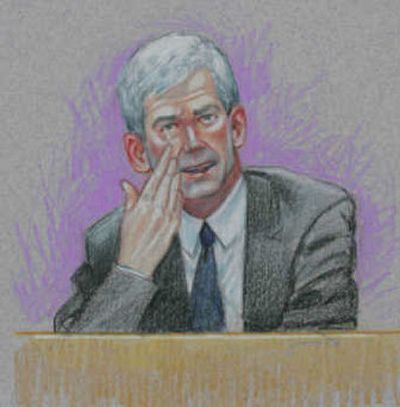

On the witness stand, Fastow was contrite, and confident when he spoke. He broke down complex financial arrangements and energy arcana into plain English for jurors.

But he struggled with tears and rubbed his eyes in anguish when the questions turned to his family.

Lea Fastow, a former assistant treasurer at Enron, served a one-year prison term for signing a tax return that failed to declare her husband’s illegal kickbacks as income.

Fighting to compose himself, Fastow told jurors Tuesday that he had misled his wife by telling her the kickbacks, a series of checks made out to him, her and their two young sons, were actually gifts. Lea Fastow endorsed and deposited them.

“I did this,” he said. “I led her to believe that.”

He also grew emotional when, under questioning from federal prosecutor John Hueston, he acknowledged committing crimes in order to manipulate Enron earnings and enrich himself.

He originally pleaded not guilty but changed the plea, he said, because “I thought it was in the best interest of my family not to go to trial, to take responsibility for my actions and to try to move forward in my life.”

The partnerships that Fastow said Skilling approved — LJM1 and LJM2 — were named with initials of his wife and sons, Jeffrey and Matthew, though Fastow did not share that detail with jurors.

He said the vehicles gave Enron a buyer of risky investments or poor assets so the company could record income and wipe debt off its books.

Fastow told jurors LJM1, set up in 1999, helped Enron head off potential future losses from its investment in a small Internet startup firm. But LJM1 couldn’t do many other deals because it only had $15 million in investment capital, so Fastow talked to Skilling later that year about setting up LJM2 with at least $200 million.

Fastow’s entrance caused heads to turn inside the packed ninth-floor courtroom in Houston. His testimony has been the most highly anticipated moment to date in the trial of Enron founder Lay and Skilling, who face fraud, conspiracy and other charges.