One final hurrah

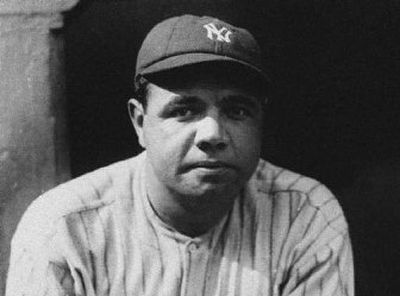

PITTSBURGH – Babe Ruth was 40 years old, with a pot belly that couldn’t be supported by his spindly legs and a fast-growing realization his career was over.

His batting average hovered nearly 200 points below his career average of .343, and the Boston Braves’ pitchers were upset at his inability to run down even the easiest of fly balls. He couldn’t run, couldn’t field, couldn’t hide in a sport that was 35 years away from having a designated hitter.

But the Babe still had something left in him exactly 71 years ago today, when he and the downtrodden Braves wrapped up a three-game series in Pittsburgh. Ruth still had the grandest home-run stroke the game has ever seen, and he powered not one, not two, but three homers that sunny Saturday afternoon – Nos. 712, 713 and 714, the last the Sultan would ever swat.

Fittingly for the man who almost single-handedly brought the home run into prominence and remains a household name to this day, Ruth’s last home run was something grand, something enduring.

No. 714 was the first to travel over the mammoth right-field roof at then 26-year-old Forbes Field, a feat only nine other men achieved before the ballpark closed in 1970. The prodigious drive was estimated at more than 500 feet, a Ruthian shot indeed.

“Boy, that last one felt good,” Ruth told Pirates rookie Mace Brown, the pitcher related in a 1995 interview with the Associated Press. When Ruth left the game, he plopped down on the Pirates bench beside Brown, since all visiting players exited the field through the home dugout.

It was a proper send-off for the Babe – a long, lasting goodbye of a home run. Sam Sciullo, then a 13-year-old Pittsburgh schoolboy and later a prominent lawyer who represented numerous Pitt coaches, didn’t know he had had seen the Babe’s last homer that day, but realized he had seen something special.

So while his father went to a friend’s house after the game, Sciullo waited and waited outside the press gate for a glimpse of the great man. His patience was rewarded when Ruth, wearing an expensive camel hair jacket and a brown cap, finally emerged.

A dozen others crowded around for autographs, but Ruth – downcast and somber despite his big day – declined to sign after willingly giving his signature the previous two days. Undeterred, Sciullo tagged along as Ruth began ambling toward the nearby Schenley Hotel, where visiting ballclubs stayed.

“He didn’t say ‘Get the hell out of the way,’ he didn’t say anything,” Sciullo said Wednesday. “I was the only one with him and I kept asking, ‘Please, Babe, give me an autograph.’ But he didn’t say one word to me. He looked so sad, he really did, and after that he played in only one more game and he retired. That was it.”

The reason for Ruth’s discontent was evident. He had long wanted to manage the Yankees, but Hall of Fame manager Joe McCarthy wasn’t about to step aside. The Yankees didn’t want their greatest player ever going to another A.L. club, so when the money-losing N.L. Braves offered him a job as a player, vice president and “assistant manager,” Ruth was allowed to take it.

But Braves manager Bill McKechnie, himself a future Hall of Famer, had no plans to quit, as Ruth soon discovered. Realizing he had been lured to Boston mostly to pump up attendance, Ruth tried to retire barely a month into the season. Team owner Emil “Judge” Fuchs persuaded him to stay on, mostly because the Braves had yet to visit some cities where Babe Ruth Days were planned.

Ruth finally quit on June 2, 1935, and never played again. He also never managed. The Braves went on to finish 38-115, with a .248 winning percentage lower that of the 1962 Mets. Fuchs lost the club soon after for financial reasons.

Back in Pittsburgh, some then-young fans who saw the Babe’s last big jolt went on to see, if only on television, Hank Aaron break Ruth’s career home run record in 1974 and, last week, former Pirates star Barry Bonds match Ruth’s total.

Among them are Paul Warhola, who, as a youngster, successfully obtained Ruth’s autograph that week. At the time, Warhola occasionally dragged a younger brother who wasn’t much interested in sports to occasional Pirates games. Andy Warhol never developed much of a love of baseball, but pioneered pop art culture, and is now honored with a museum and a bridge in Pittsburgh.

Sam Sciullo never had much use for Bonds or McGwire, but has clung to his memories of Ruth. He said, laughing, “That’s probably my claim to fame, that I was the last kid to walk with Babe Ruth in the city of Pittsburgh.”