Dozens pass dying man on Everest

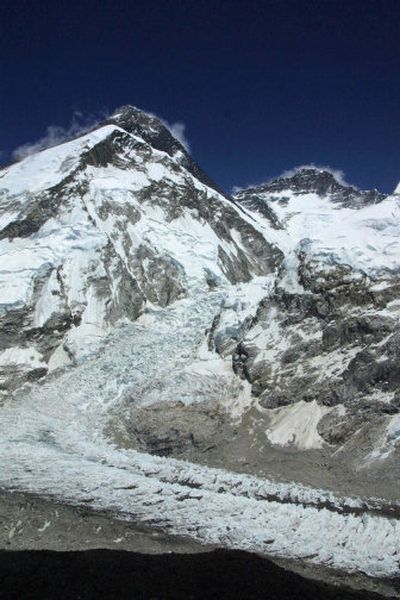

KATMANDU, Nepal – The story, an open secret in the crowded nylon city of Mount Everest base camp, trickled out from the high Himalayas: a British mountaineer desperate for oxygen had collapsed along a well-traveled route to the summit.

Dozens of people walked right past him, unwilling to risk their own ascents.

Within hours, David Sharp, 34, was dead.

The tale was shocking, an apparent display of preening callousness. Sir Edmund Hillary, who was on the team that first summitted Everest in 1953, called it “horrifying” that climbers would leave a dying man.

But in the small world of modern high-altitude mountaineers, there was barely any surprise at all.

That, in part, reflects the dangers inherent in climbing to a place where temperatures are so low that skin can freeze instantaneously and oxygen levels can barely sustain life. When things go wrong, there is little chance of rescue.

But, many climbers add, Sharp’s death also reflects something else: a changed ethic in what was, until a couple decades ago, a tiny community where only the most experienced climbers would be found that high on a mountain – and where a dying climber would be abandoned only when a rescue threatened other lives.

In Sharp’s case, about 40 people are thought to have walked past him as he sat cross-legged in a shallow snow cave. The few who stopped to check on him – and at least one team did give him oxygen – said he was so near death there was nothing that could be done.

“We’ve been seeing things like this for a very long time,” said Thomas Sjogren, a Swedish mountaineer who helps run ExplorersWeb, a Web site widely read by climbers. “The real high-altitude mountaineers, the top people in the world who are doing new peaks and going to mountains you don’t know much about, most of these people have become completely disgusted by Everest.”

The top mountaineers “often help each other,” said Sjogren, who has made many Himalayan climbs. “If you know him or you don’t know him, it doesn’t matter: you try to help him until he’s confirmed dead.”

But many of today’s Everest climbers are on commercial expeditions, some paying tens of thousands of dollars to guides who are under fierce pressure to get their clients to the summit.

The situation grows more complicated when many climbers don’t have the skills to help someone like Sharp, and perhaps shouldn’t be on the mountain at all.

“The sheer pressure of numbers and accessibility to these mountains (has) changed the kind of people who go,” said Lydia Bradey, a 44-year-old New Zealander who in 1988 became the first woman to summit Everest without supplemental oxygen.

As a result, Bradey said in a telephone interview, Everest climbers may be forced to decide whether to jeopardize their once-in-a-lifetime investment to help a dying person.

“If you’re going to go to Everest … I think you have to accept responsibility that you may end up doing something that’s not very ethically nice,” she said. “You have to realize that you’re in a different world.”

It’s a world not meant for people at all, where oxygen levels are a tiny fraction of what they are at sea level, temperatures can drop to 100 degrees below zero, and winds can blow with the force of a gale. The area above about 26,000 feet is referred to simply as the death zone.

At those altitudes, the combination of exhaustion and low oxygen can leave even the best climbers lost in dreamy hallucinations of warmth and comfort.

The mountaineers who passed Sharp said he appeared unprepared for his solo climb to the summit, with limited oxygen supplies. Sharp, an experienced climber, had tried to summit Everest twice before in previous years.

The team of New Zealander Mark Inglis, the world’s first double-amputee to reach the summit, stopped to give Sharp oxygen before continuing to the top.

“The trouble is that at 8,500 meters (27,887 feet) it is extremely difficult to keep yourself alive, let alone keep anyone else alive,” Inglis told New Zealand television. “We couldn’t do anything. He had no oxygen, no proper gloves, things like that.”

Other climbers said Sharp, presumably incoherent, had also taken off his jacket.

Sharp, an engineer, died May 15, about 1,000 feet into his descent from the summit.

More than 1,500 climbers have reached the summit of Everest in the last 53 years and some 190 have died trying.

On May 10, 1996, a combination of bad weather, crowded routes and inexperienced teams left eight people dead on Everest in just one day, a horror that made headlines around the world.

While that day did much to expose the surreal vision of modern Everest – with its base camp cappuccino machines, bickering teams and barely experienced climbers being “short-roped” up the mountain by guides – it has done nothing to slow the commercialization of the mountain.

“People need to accept – the public as well as climbers – that people will die,” said Alan Hinkes, the first Briton to climb all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks.

“People don’t understand or accept it,” he said “They think they’ve bought into a theme park.”