That perfect day

The perfect afternoon began with moments of serious doubt.

As Don Larsen arrived in the Yankee clubhouse before Game 5 of the 1956 World Series, teammates Hank Bauer and Bill “Moose” Skowron watched him stroll toward his locker. Larsen looked down at his spikes and discovered a new baseball tucked into one, the old-time sign that he would be the starting pitcher against the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Larsen looked at the ball for a moment. “I took a big swallow and said to myself, `Don’t screw it up, like last time,” recalls Larsen, who couldn’t get out of the second inning in his Game 2 start at Ebbets Field.

Across the room, Bauer and Skowron watched in disbelief. This guy is pitching? Rumors have rumbled through the clubhouse that morning that Larsen, a party guy who once described himself as “The Nightrider,” had been out carousing the previous evening.

“I couldn’t believe he was pitching that day,” adds Skowron. “I still can’t believe the look he had on his face when he saw the ball – shock or something. We had heard he tied one on, though I don’t know if it’s true.”

A few hours later, Larsen would accomplish something that hadn’t been done before and hasn’t since – he retired all 27 batters to throw a perfect game in the World Series, beating the powerful Dodgers, 2-0.

“The unperfect man pitched a perfect game,” read the Daily News’ game story the next day, one of the most famous first sentences in sports writing. “Zero Hero!” blared the cover.

The comic-book loving Larsen, a former 21-game loser whose other nickname was “Goony Bird,” had gone from wondering if he would ever pitch again for Casey Stengel to baseball immortality. Now 77 and enjoying retirement and fishing around his Hayden Lake home, Larsen thinks about Oct. 8, 1956 nearly every day.

The day was unseasonably warm and the sun dappled Yankee Stadium as a slight haze hung over the park – many of the 64,519 fans at the game were smoking cigarettes.

After Larsen saw the ball in his cleat, put there by coach Frank Crosetti, he disappeared. “I just got away from everyone to get my senses back,” Larsen says.

Later, he went to the bullpen to warm up with the backup catcher, Charlie Silvera. “He warmed up very casually,” Silvera says. “It wasn’t like I went to anybody and said, `He really has it, we’re in.’ He warmed up the same way he had for Game 2.”

In the first inning, Larsen went to his only three-ball count of the day, on No. 2 hitter Pee Wee Reese, but Reese struck out looking. Leadoff man Jim Gilliam also struck out looking and Duke Snider lined to right.

Larsen, who had the best season of his career in 1956, going 11-5 with a 3.26 ERA, had devised a no-windup motion toward the end of the season because he was losing control of his pitches. But everything was crisp on that day and he was backed by Mantle’s fourth-inning homer and an RBI single by Bauer.

“His stuff was good, good, good,” says Yogi Berra, who caught the game. “Anything I put down, he put over.”

In the second inning, cleanup hitter Jackie Robinson lashed a ball that deflected off third baseman Andy Carey to shortstop Gil McDougald and McDougald threw out Robinson at first. Carey, who according to the Daily News had been “the sloppiest man in the series afield,” also snared a low liner by Gil Hodges in the eighth after bobbling it.

“It was only the fourth out,” Larsen says of the ricochet play. “You don’t expect it to be something.”

The fifth inning was perhaps Larsen’s biggest challenge. With one out, Hodges slammed a long drive to left-center that “would be a home run in any park today,” Larsen says. It also likely would have been a homer if the game had been at Ebbets Field instead of Yankee Stadium. But Mantle chased it down and backhanded it.

Way up past third base, from a seat in the top deck, a 16-year-old Joe Torre watched Mantle run. “It looked like he was coming right toward me,” Torre says.

The next batter, diminutive Brooklyn outfielder Sandy Amoros, walloped a liner into the right-field stands, but it veered to the right side of the foul pole. Asked by the Daily News’ Dick Young how far the ball was foul, right-field line ump Ed Runge spread his thumb and index finger an inch apart and replied, “That much.”

Years later, Larsen talked to Runge himself about the drive. Both men lived in the San Diego area and were friendly. “I never knew it was that close,” Larsen says now.

By now, others in the Stadium were beginning to realize what was going on. In the press box, public address announcer Bob Sheppard was feeling the tension. “It began for me about then and, I think, for the fans,” says Sheppard, who was only five years into the job.

Bauer looked at the scoreboard and thought, “Goony Bird is pitching pretty good.”

In the Dodgers’ dugout, Snider recalls someone saying, “Hey, somebody get a hit. He’s got a no-hitter going.”

The Yankee dugout, normally a jovial place where players would backslap each other and exchange tips on the opposing pitcher, went silent, players following the old tradition of not speaking to a pitcher in the middle of a no-hitter for fear of a jinx. Larsen sat by himself while his teammates tried not to even move.

“I had no tension on the mound,” Larsen says. “But the dugout was a morgue. No one would talk to me. I was more comfortable on the mound than there.”

Around the same time, Sheppard began “holding my breath” with each Brooklyn hitter. “I think the fans were doing the same thing,” Sheppard says.

Out in the bullpen, Silvera grabbed his mitt. Stengel wanted Whitey Ford ready to pitch in case Larsen got in trouble. It was, after all, only a two-run game. Ford warmed up in the eighth and the ninth.

In the ninth, Larsen retired Carl Furillo on a liner to right and Ford quit throwing. “Whitey was hot, ready to go,” Silvera says. “We stopped and said, `Let’s watch now.”’

Larsen got Roy Campanella on a grounder and Brooklyn manager Walter Alston tabbed Dale Mitchell, a lifetime .312 hitter, to be the 27th man and bat for Maglie. Sheppard’s heart dropped.

“I had known Dale Mitchell as a pesky hitter who could hit it here and everywhere,” Sheppard says. “If anyone was going to spoil this masterpiece, it was a hitter like Dale Mitchell. I prayed and prayed and prayed.”

Mitchell, who struck out only 119 times in 3,984 career at-bats, or once every 33.5 trips to the plate, half-swung at strike three, a pitch that may have been high. It was Larsen’s 97th pitch. “I’m glad he didn’t take a full swing at it, he was a helluva hitter,” Larsen says.

Snider still believes the umpire, Babe Pinelli, made a bad call. “He was umpiring his last game,” says Snider, now 80. “And I think he wanted to go out with a no-hitter. I don’t know if Yogi would admit it, but it was outside. I talked to (Mitchell) afterward and he said, ‘Duke, it was six inches outside.’ ” But there were 26 outs before that and he got them all. You can’t take anything away from him.”

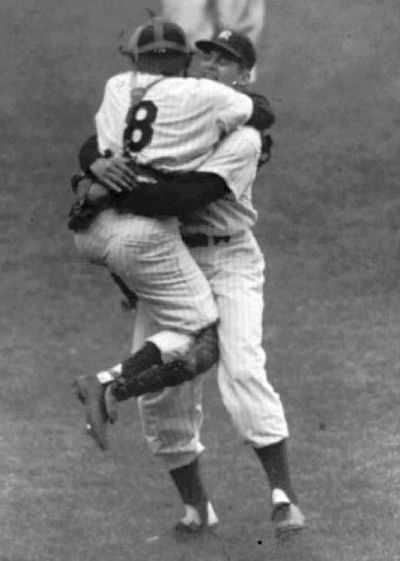

Berra bolted from the behind the plate and leaped into the 6-4, 225-pound Larsen’s arms, creating one of the game’s most famous photo ops. Berra still has the photo of Larsen hugging him hanging at his home and in his museum.

“I was so happy, it just happened,” Berra says.

“He jumped on me,” Larsen says. “My mind probably went blank. Maybe still is.”