The Sopranos’ returns tonight for the first of nine episodes that will bring to a close one of history’s most influential TV dramas

That may sound like hyperbole, but please note the choice of words: I didn’t say it was the most important, the most entertaining or even the best program ever.

Despite a disappointing sixth season last year, “The Sopranos” – which returns for its final nine episodes beginning tonight – is certainly near the top of the list in all of those categories, no question.

But Tony Soprano and his crew occupy a more specific niche: No one-hour drama series has had a bigger impact on how stories are told on the small screen, or more influence on what kind of fare we’ve been offered by an ever-growing array of television networks.

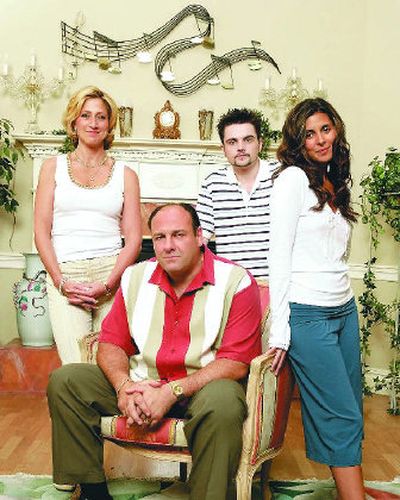

“The Sopranos,” which debuted on HBO Jan. 10, 1999, soon became a cultural phenomenon, then a ratings phenomenon. The complicated drama about a mob boss, his family, his shrink and his crew garnered critical raves, stacks of awards and endless media coverage for an ascendant HBO.

But a more salient fact for television executives was that, at its peak, Tony Soprano (played by James Gandolfini) and his crew attracted an audience of 12 million every week.

In today’s fractured media environment, that is a very respectable figure for a program on a broadcast network. For a show on cable – and premium cable, at that – that figure was, and still is, jaw-dropping. Most cable dramas would kill to pull in half (or a third) of that.

Television executives didn’t have to be rocket scientists to take away the following lessons from the success of “The Sopranos”:

“Dark, challenging storytelling can draw a large number of viewers and a torrent of critical praise.

“Using film-quality production values and top-notch writing will garner more good press than any ad campaign can buy.

“Casting less famous but gifted actors can not only save money but also pay off during awards season.

“A risk-taking, successful, buzzed-about show will not just rake in high-income viewers and the advertisers who chase them, it can brand a cable network and put it on the cultural map.

” ‘The Sopranos’ demonstrated what could be accomplished with continuing story lines that grew organically out of three-dimensional characters,” says David Weddle, a “Battlestar Galactica” supervising producer.

“The show demonstrated … that by following the lives of characters over a period of years, one could fashion an epic narrative with all the textured complexity of an epic novel such as ‘War and Peace.’ Feature films cannot even begin to approach narratives of this scope and complexity, so it put to rest once and for all the notion that television is an inferior medium.”

All this from a program whose opening image was of a man sitting in a psychiatrist’s office, waiting to talk about his crippling panic attacks – which began when the family of ducks nesting in his backyard took off for good. That small moment set in motion a wrenching reassessment of Tony Soprano’s supposedly contented suburban life.

Rewatching that first episode of “The Sopranos,” you realize how much of it had nothing to do with mobster lore. Tony’s tenderness toward the young ducks in his pool was an outgrowth of his own desire to be taken care of, to preserve some innocence in what he knew to be a cold and cruel world.

If “The Sopranos” had just been about a Mafia boss who whacked people and hung out at a strip club, it would have lasted a season or two, if that. Creator David Chase was far more interested in exploring how a man with a volcanic temper and a bewitching degree of power could hang on to some kind of ethical code, all the while battling the negativity emanating from his black hole of a mother and a world that expected mere violence and materialism from him.

“The Sopranos” is a classic exploration of the underside of the American dream – something that anyone, of any ethnicity or income level, can understand.

And Tony may be a made man, but the Mafia is by no means the show’s main or only subject matter. If anything, Soprano and his fellow mobsters know they are quite literally a dying breed, and that’s what informs the show’s evocative meditations on mortality.

Even when it did delve into the world of the mob – admittedly, one of the attractions for some viewers – “The Sopranos” upended expectations.

Adriana La Cerva, fiance of mobster-in-training Christopher, could have been just another stereotype – a big-haired, big-mouthed Jersey girl sporting fake nails and tight pants. But thanks to Drea de Matteo’s impassioned performance and the show’s commitment to building real, nuanced characters, the murder of Adriana near the end of season five ranks as one of the most wrenching deaths in TV history.

When Tony murdered a man during a college visit with his teen daughter during the show’s first season, it was a turning point in television history. Viewers of “The Sopranos” knew from the get-go that they were watching a show about a man involved in shady, perhaps gruesome activities, but for Chase to show the worst that Tony was capable of – and still expect viewers to keep tuning in – took chutzpah, not to mention patient, skilled character development and a towering performance from Gandolfini.

Contrast that with Ray Liotta’s character on “Smith,” last fall’s failed heist drama on CBS: When he killed a security guard in that show’s pilot, it felt like a cheap stunt.

FX’s “The Shield,” which in its 2002 pilot had take-no-prisoners cop Vic Mackey (Michael Chiklis) kill a fellow officer – now that was the right way to build upon the “Sopranos” legacy of moral ambiguity.

The writing for that FX cop drama is every bit as surprising and compelling as what we’ve seen on HBO in the last eight years, with the morally challenged Mackey providing a window into a dark, restless soul in a violent search of redemption.

The same rigorous, challenging writing informs Showtime’s darkly cynical “Dexter” and “Weeds”; Sci Fi’s brave “Battlestar Galactica”; and HBO’s own “Rome,” “The Wire” and “Deadwood.”

For the last eight years, television executives, writers, producers, directors and actors have looked to “The Sopranos” as a benchmark of quality.

This series hasn’t just shown us what television is capable of. It’s shown us what filmed storytelling is capable of.