Albi complex still in question

Spokane voters spoke – more than eight years ago.

But a sports complex at Joe Albi Stadium – approved with 80 percent voter support – remains unbuilt.

Neighborhood concerns about traffic, competing sports programs, opposition to the sale of alcohol and city budget shortfalls have consistently derailed the plan.

Spokane leaders say a new effort led by Councilman Rob Crow, partly to use some land for a softball complex, could break through the quagmire. Still, a meeting on the proposal held last week illustrated that some battles remain – principally between baseball and softball interests.

The Spokane North Little League, noting that alcohol might be sold during adult softball games, is rallying parents against the proposal. Its Web site says the plan would mean the land would be “lost to adult sports forever.”

Crow argues that there’s more to the first phase of the Albi plan than softball, including improved youth soccer fields, walking trails, a BMX track and possibly a skateboard park. He adds that youth participation makes up about 35 percent of the players in the Spokane Amateur Softball Association, and their participation is growing.

In 1999, voters approved the sale of parkland that was a converted sewer lagoon on Holland Avenue. The city was to use money from the sale of the property, which was bought by Wal-Mart, to build a sports complex next to Joe Albi. Ballot language didn’t specify what sports would be part of the complex, but parks officials said all along that softball would be a main portion of the park, in part because they felt softball tournaments could generate enough revenue to maintain operations.

Money from the land sale sits collecting interest. There’s almost $4 million from the land sale that could be used for the project, Crow said. An extra $1 million to $2 million needed for the first phase could come from city reserves, or the city could bond for the extra money, he said.

Jim Albi, a cousin of Joe Albi and founder of Friends of Albi, said he supports Crow’s efforts.

“We can accommodate a cross section of our city, young and old – all people – to have a place to recreate,” Albi said. “That’s what Joe was all about.”

Baseball v. softball

Crow said softball remains on the table because park board and city leaders told voters softball would be part of the project. In addition, he said, demand for softball remains high.

“Softball tournaments are capable of covering most, if not all of their operations and maintenance costs,” Crow said.

But Dan Peck, president of the Spokane North Little League, said demand for youth baseball has increased tremendously since the vote. The public is more sympathetic to the needs for youth sports than adult softball leagues, he said.

“They already have a softball complex,” Peck said, noting fields at Franklin Park. “Why should they get a second complex before youth baseball gets any sort of complex?”

Fuzzy Buckenburger, commissioner for the Spokane Amateur Softball Association, said about 800 teams consisting of some 10,000 people participate in the association. He added that building a softball complex would open up fields for youth baseball throughout the park system.

Peck said youth baseball teams can use softball fields but that they can’t be used for tournaments. A softball field doesn’t have a pitcher’s mound or infield grass.

Crow said the debate illustrates that the city has too long ignored the need for more sports fields.

“This is step one in a multi-step process,” Crow said, adding that the city is considering putting a baseball complex at Playfair, a former horse track purchased by the city in 2004.

But Peck said many parents would not want their kids to play in that part of the East Central neighborhood because of a history of crime and prostitution along nearby East Sprague Avenue.

“Is that really where you want to drop your 9- or 10-year-old kids off?” Peck said.

Crow said developing Playfair into a park, along with the expansion of the city’s university district, would make the area more kid-friendly. Killing the softball proposal could ultimately hurt the chances that more baseball fields will get built, he said.

“That’s the myopia that inhibits progress,” Crow said.

Alcohol

Concerns about alcohol have derailed the softball complex before. The land eventually purchased by Wal-Mart was supposed to be used for softball until neighbors complained about the idea, in part, because of potential alcohol sales. Existing softball fields, like most other park land, don’t allow alcohol.

Crow said selling alcohol at the new complex during tournaments could generate between $80,000 to $120,000 a year. Not selling beer or wine, however, won’t doom the project, he said. But it would mean the project would likely need more tax dollars to survive.

Buckenburger also said alcohol isn’t a deal-breaker.

“My wish is to have enough revenue so we don’t need it,” he said.

Peck told Crow and others at the Albi meeting last week that if alcohol is allowed, a neighborhood child is sure to be run over and killed by a drunken driver.

“As sure as I’m sitting here, it’s going to happen,” he said, adding that selling alcohol is a bad example to kids who might be playing nearby.

Many others sitting around the table, however, said that with proper restrictions, alcohol sales wouldn’t endanger kids any more than other hazards.

More land, walking trails

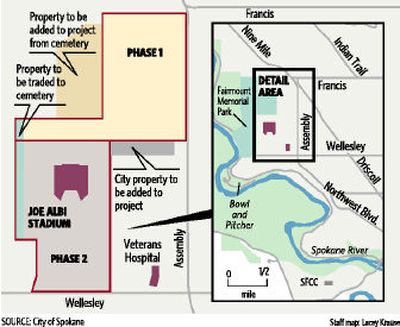

The new Albi proposal includes about nine acres more than the last significant effort to develop the park that failed in 2004.

That’s because Fairmount Memorial Park is considering a proposal to give the city 14 acres of wooded land in exchange for about five acres next to Albi.

Duane Broyles, president of the Fairmount Memorial Association, said that the 120-acre cemetery can afford to give up some land because of the increasing popularity of cremation. About 87 acres of the park are filled.

“Our land-use needs are less than they’ve ever been,” Broyle said.

Broyles said he would like to relocate the Fairmount’s maintenance shop to the side, on Albi land, to make it less of a distraction in the cemetery.

If the city gained the cemetery land, it mostly would be kept in its natural state for walking trails, Crow said.

Neighbors of Albi Stadium fought the last effort because of traffic and other concerns. This time, however, the Northwest Neighborhood Council overwhelmingly endorsed an Albi plan late last year that included softball.

Karen Bell, chairwoman of the council, said the new land helped change minds because it provides a link to Riverside State Park and gives nearby residents a great place to walk.

“That’s just a wonderful opportunity,” Bell said. “It’s too good to pass up.”

The stadium

Discussions also are taking place about Joe Albi Stadium and the southern portion of the property.

The stadium has long been a drain on the city budget. So much so that in 2005, former Mayor Jim West proposed selling the southern portion of the land that includes the stadium to developers for less than what the property was valued by the county assessor’s office.

His plan was shot down by City Council. Crow said it was a wake-up call that action was needed to save the public space.

Crow has asked the Spokane Public Facilities District to consider taking over the stadium in an attempt to increase attractions at the field and help it at least break even. The district operates the Spokane Convention Center and Spokane Arena.

“There’s no question that Albi is an underutilized asset,” said Councilman Brad Stark, who said he supports Crow’s attempts to move the Albi project ahead. Stark was the only councilman who supported West’s plan to sell Albi.

The 26,000-seat stadium once hosted Elvis Presley and was a college sports venue. But it’s now mostly used only for high school sports.

Crow has worked with a six-member committee, which includes Bell of the Northwest neighborhood, on the Albi land proposal.

“If I make 70 percent of the people happy, I’m thrilled,” Crow said. “That means 30 percent of the people are going to be unhappy.”