High-powered motor

KIRKLAND, Wash. – There is so much gas in Seattle about Patrick Kerney’s motor, you’d think the Seahawks’ biggest free agent signing this off-season was a souped-up car.

A $39.5 million car, that is.

“His motor never stops,” said Seahawks defensive backs coach Jim Mora, the defensive end’s head coach with the Atlanta Falcons from 2004 through last season, when Kerney missed the last seven games due to a torn pectoral muscle.

Besides being a relentless menace to quarterbacks, the 2004 Pro Bowler is also a licensed pilot who owns a four-seat plane. He said meeting two dozen crew members of the Navy’s Blue Angels performance flying team after practice Monday was “awesome.”

“I asked them how far apart they fly, and they said 18 inches! When I’m in the air and I see a plane within a mile of me, I’m out of there the other way,” Kerney said, adding he is no longer flying now that he’s so far away from family while in Seattle.

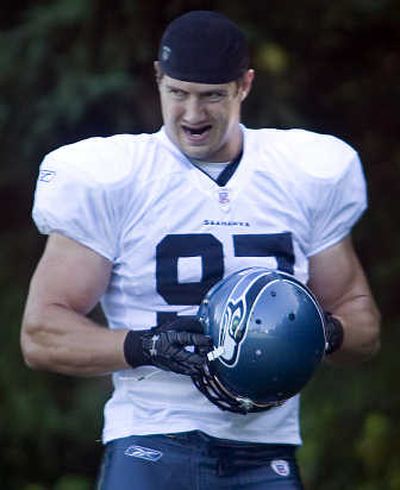

Kerney spent his Monday morning repeatedly blowing past and through Tom Ashworth, a former Super Bowl starting tackle with the New England Patriots. He’s 6-foot-5, 272 pounds, with biceps as wide and hard as cinder blocks. He has a billboard-sized chest recently reinforced by successful rehabilitation following surgery to repair the torn muscle last November.

He is also a history major from the University of Virginia who attended The Taft School, a prestigious boarding school on an idyllic campus spread across 220 acres in Watertown, Conn.

“He’s breaking a lot of stereotypes,” Seahawks quarterback Matt Hasselbeck said of Kerney.

Kerney, 29, comes across as a mild-mannered, soft-spoken bachelor with a large, bright grin. But he grew up in Eastern Pennsylvania as a huge fan of the “Broad Street Bullies,” the Philadelphia Flyers of the early 1980s.

But this connoisseur of collisions also contributes thousands of dollars each year to send to college children of police officers whose fathers have died in the line of duty.

“It’s just the fiber of who he is. He attacks life,” Mora said. “If you get to know Pat, and you see how he does things, it’s always full-go.”

Kerney and other Falcons were at Mora’s press conference when Atlanta hired Mora as its coach. Unlike his teammates, who sat quietly and simply exchanged pleasantries with the new leader, Kerney jumped him.

“He was like, ‘OK. Let’s go. What are we going to do. What’s our plan?’,” Mora said. “Immediately. Five minutes into my tenure, and he wanted to know. Pat was in my face. That’s just the way he is.”

Soon after Kearney entered the NFL as the 30th overall selection in the 1999 draft, he established the Lt. Thomas L. Kerney Endowment Fund. Thomas Kerney was Patrick’s older brother, an Army veteran and police officer who died in the line of duty.

Patrick honors his big brother by pointing to the sky at the conclusion of the national anthem before each game. For each sack, Kerney puts $2,000 into the grass roots fund. For his career-best season of 2004, he contributed $26,000.

The money has sent a half dozen children to college. It also helps pay for the everyday lives of dozens more spouses whose police officer mates have died, leaving children behind.

“I’ve used his presence to propel me, inspire me,” Kerney said of his brother. “I think most NFL players realize how circumstantial our success is, that we owe so much more to our success than just ourselves. So I want to do something to give back that has been meaningful to me and my family.”