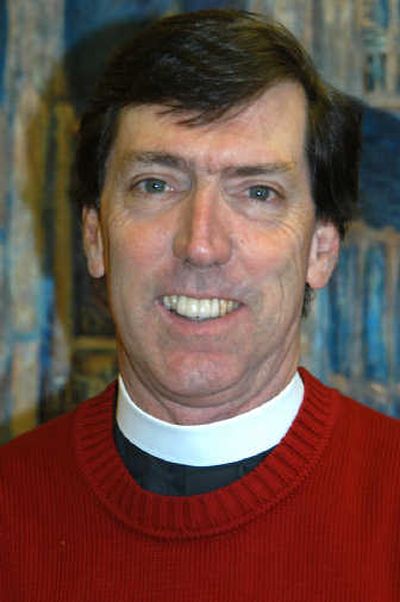

Preaching peace

The dean of Spokane’s Episcopal Cathedral of St. John, the Very Rev. Bill Ellis, regularly challenges his congregation to dare to imagine a future fulfillment that is not the product of human endeavor, but is a gift of God received gratefully.

“Most of us can imagine a reasonably peaceful future for ourselves and those we love, but we are also keenly aware that the future we imagine is lived against the backdrop of an increasing spiral of human violence,” he said.

Ellis is thankful that the scriptural imagination dares to envision “a world whose end is not apocalyptic violence, but delivered from that end by unconditional forgiveness that breaks the cycle of reciprocal violence and so founds a new heaven and a new earth.”

Once the cruciform Gothic cathedral on the South Hill was an ecumenical spiritual center, a focal point for art, music and social life, and the place where the movers and shakers of Spokane’s political and financial power structures worshipped.

While the cathedral still serves as an important center of religious and cultural life, Ellis said that in today’s “none zone” culture – most Northwest people polled claim no religious affiliation – the cathedral, like most Inland Northwest churches, no longer enjoys the significance it once had.

Today, most of the cathedral’s 600 members are ordinary, middle-class people, he said.

“Now in a wilderness period, we are still about what the church has always been about, proclaiming the Gospel and living it out,” Ellis said.

He brings insights from studying history at the University of Oregon in Eugene. He set aside plans to study law in order to study theology at the Church Divinity School of the Pacific in Berkeley, Calif.

Since graduating in 1982, Ellis has served Episcopal churches in Coos Bay and Reedsport, Ore., followed by eight years in Forest Grove and 10 years in Bend. He came to the cathedral in September 2006.

Ellis’ commitment to nonviolence means he does not limit preaching or teaching about peace to the season of the birth of the Prince of Peace. It is a year-round theme, because it permeates the Scriptures.

On Veterans Day, for example, he connected the messages of three Scripture lessons – from Job, II Thessalonians and Luke – that speak of a future in which “all is fulfilled and redemption is at last accomplished.”

Ellis is concerned that the American approach to violence destroys the values on which the nation was built.

“We’re escalating the cycle of violence. The stakes are higher than 100 or 1,000 years ago,” he said. “Humans need to realize that use of violence to end violence does not work.

“Once governments had a monopoly on violence and might temporarily end violence but, with new communication tools and technology, no one has a monopoly on violence.

“People can form small, international cells, communicating their ideological designs through new technologies. Through other new technologies, they can invent more sophisticated means of killing than disgruntled groups in the past.”

To him, the naïve people are those who say violence will end violence. Ellis calls people to use their capacity to forgive, reconcile and fit in.

“We have to, or the world will not survive,” he said. “We will create global, cataclysmic destruction from which it will take centuries to recover.”

Ellis finds hope in unexpected places, such as the way leaders today justify violence.

“We can no longer justify violence simply for glory or imperial expansion,” he said, noting that President Bush justified the war in Iraq by saying, “We have to liberate victims of an oppressive regime.”

“The Jewish-Christian tradition of empathy is about our common humanity and God’s requirement that we not victimize other people,” Ellis said.

“The president’s justification for the invasion demonstrates that this tradition of empathy for victims has seeped deeply into our consciousness even without our realizing it.”

He also sees hope in the increasing numbers of people “sick about what we have done in Iraq and believing little has been accomplished.”

Ellis sees an evolution in thinking, like the story of the 100th monkey – the number that would tip the tide of thinking in the world to turn away from a dependence on violence.

The destruction nuclear weapons can cause is so horrible that people realize motives don’t matter, he said.

“Whether humanity has a future and what that future is are the prevailing questions,” he said. “Albert Einstein said he did not know the technology the third world war would use, but knew the weapons of the fourth world war would be sticks and rocks.”

The story of Jesus is about his choice to suffer and die rather than cause suffering or death, Ellis said.

“If in the collective experience of humanity we can become transformed by forgiveness, which has been there from the foundation of the world,” he said, “then indeed our children and their children may just see that day when the swords are beaten into plowshares and the spears into pruning hooks.”