UW group fighting for Bruce Lee statue

SEATTLE – When she closes her eyes, college sophomore Courtney Ioane can visualize the statue of Bruce Lee that she wants erected on the University of Washington campus.

It is bronze and life-size – not so big that it dominates the area but substantial enough to be noticed. And the legendary fighter would not be punching or kicking but sitting in a meditative pose.

“Bruce Lee was more than a martial artist,” said Ioane, 20. “He also had an amazing philosophy of life. He’s a cultural icon recognized all over the world – except on this campus,” where Lee studied for three years in the early 1960s.

Ioane and 20 other UW students have collected more than 1,000 signatures – including nearly all the members of the men’s and women’s basketball teams – as part of the effort to build a Bruce Lee monument.

The statue would begin to represent the diversity of cultures currently absent in the school’s collection of public-art displays, Ioane said. Nearly all the several dozen statues and busts on the sprawling 700-acre campus are of white men, including George Washington.

Of the 28,570 undergraduates at UW, more than 35 percent are minorities. One in four students is Asian-American. Ioane, from Spokane, is half-Samoan.

University officials have remained noncommittal on the project, and at least one spokesman questions whether Lee’s accomplishments merit a permanent memorial on a college campus.

If the students succeed, the statue would add to the growing list of Bruce Lee tributes worldwide. In China, streets have been named and memorials erected in his honor. A massive Bruce Lee theme park is under construction in Shunde, China. In Bosnia, a bronze Lee statue was unveiled in 2005 as a symbol of healing and unity.

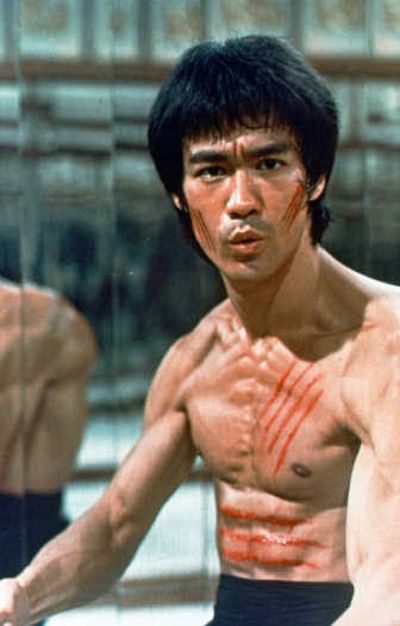

Lee was born in San Francisco and grew up in Hong Kong. His movies raised martial arts to new levels of popularity and became a source of pride for Asians and Asian-Americans who had been commonly depicted as weak in the popular media.

Lee’s 1973 movie “Enter the Dragon” was one of the highest-grossing films of that year and to date has grossed more than $200 million worldwide. Since he is routinely listed as one of the most recognizable pop-culture icons of the 20th century, it surprises some that Lee made only four movies. He died at age 32 of cerebral edema a few months after completing “Enter the Dragon.”

He is buried in Seattle.

“I’m not for taking any of the existing statues down,” said Jamil Suleman, referring to the memorials of white males on the UW campus. “I’m just for putting up statues that represent us.”

Suleman, 23, graduated from UW this year. He was born in Africa of East Indian parents. The idea for a Bruce Lee monument was his. To begin the process, Suleman formed a group on campus called “Bruce Lee Dedication.”

Walking through campus, Suleman pointed out artistic representations of William Shakespeare, Immanuel Kant, Isaac Newton and Benjamin Franklin. In front of Husky Stadium stood a statue of Jim Owens, football coach from 1957 to 1974.

“Do you see Gandhi anywhere? Or Martin Luther King or Malcolm X?” Suleman said.

While Lee didn’t graduate from UW, he attended the school for three years and often taught martial-arts classes on the lawns just outside the student union. Lee took drama and philosophy classes, and he met his wife, Linda Cadwell, here. Norm Arkans, a spokesman for the university, said proposals for public art must go through a lengthy, often years-long process. “It’s not random, it’s not willy-nilly.”

The proposal, he said, would have to emerge from a university department, go through numerous planning committees and eventually gain the approval of school administration. But even if Suleman’s group were to go through all the hoops, nothing is guaranteed.

“One has to ask oneself, in terms of receiving individual recognition on campus, what claim to fame did Bruce Lee have?” Arkans said. “He became a famous personage in one genre of movies. I don’t know if he had other claims to fame.”

Arkans added, however, that the university would give the idea due consideration.

“As far as I know, nothing has been submitted yet,” he said. “It’s hard to have a response to something we haven’t seen.”

And it’s not entirely true that minorities are unrepresented on campus, Arkans pointed out.

In 2005, the university unveiled a student-created artwork called “Blocked Out,” which features a small rolling lawn on which a giant ear is built from stones. On the other side of the lawn stands a granite cube – simulating an auction block where slaves were sold – imprinted with bare footprints facing the ear, as if an unseen person is finally being heard.

A nearby plaque reads: “Dedicated to those who were excluded from the home they were exploited to create.”

Critics of “Blocked Out” say it is too abstract, and most passers-by wouldn’t know what to make of it. A statue of Bruce Lee, however, would be instantly recognizable, said Ioane.

“The university throws around the word ‘diversity’ a lot,” she said. “We’re trying to find out whether (university administrators) really mean it, or they’re just talking.”