Johnson gave Seattle taste of Huck Finn

D.J. died Thursday.

A hardcore gym rat who always treated basketball as if it were life-sustaining, as if it gave meaning to everything else he did, D.J. died after suffering a heart attack following an Austin Toros practice.

A guy who played with the hunger of a club fighter living from paycheck to paycheck, Dennis Johnson, who was the coach of the National Basketball Development League team in Austin, is dead at age 52.

And all the 40-, 50- and 60-somethings, who watched the Sonics make consecutive trips to the NBA Finals and win it all in 1979, are mourning him today as if he were kin.

The impact he had on Seattle is difficult to believe now, because the league has changed so much, become bigger and richer and less in touch with the true fans.

But back in the day when the Sonics were the best team in basketball and the toast of Seattle, fans used to hang out after games in places like Duke’s or F.X. McRory’s and wait for the players to come in.

It was a simpler time in Seattle sports. The city was less sophisticated and more than a little naïve.

The Sonics were setting attendance records and the franchise didn’t need $500 million for a new building. The entire NBA had a populist feel to it.

The Sonics practically felt like a college team, and the restaurants they visited after games were part of their campus,

Jack Sikma and Gus Williams, Freddy Brown and John Johnson would walk in and you felt like you knew them. They weren’t merely players. They were neighbors. They celebrated with you.

They were real. They were us.

The NBA was a much different league in the 1970s. It was struggling for recognition, a distant third in popularity behind Major League Baseball and the NFL.

But in Seattle, the Sonics were kings. The Mariners and Seahawks were new and not good.

The Sonics were winners.

The success of this team, coached by Lenny Wilkens and nurtured by the veteran Paul Silas, coincided with the growth of the city. The Sonics were big at a time when Seattle was getting bigger. The Sonics were playing for championships when the rest of the country was starting to notice the Northwest.

And, on what I believe still is Seattle’s all-time favorite team – its first modern-day world championship team – D.J. was one of the city’s favorites.

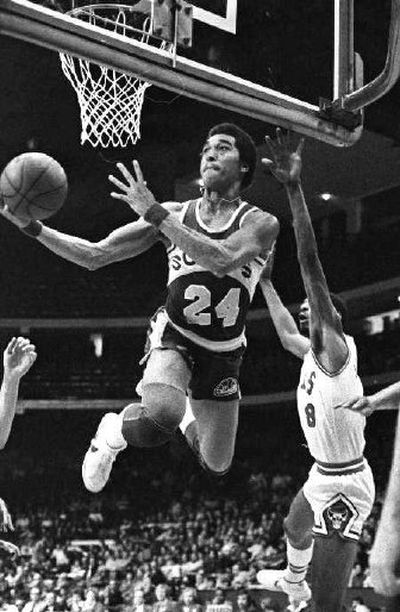

He came to the Sonics from Pepperdine – Seattle drafted Bobby Wilkerson and Bayard Forrest ahead of him in 1976 – with a reputation for being difficult to defend, difficult to score against and, yes, difficult to coach.

He was sly and sardonic and fearless. D.J. never ran away from a game-winning shot and always asked to guard the other team’s best player.

D.J. was unique. He wasn’t the quickest Sonic. He was better than his numbers. He was the definition of a streak shooter. He even went 0 for 14 in the final game of the 1978 championship series against Washington.

(When he missed his first shot in the first meeting of the next season against Washington, Bullets coach Dick Motta barked, “0 for 15.”)

He had his flaws, but D.J. was a great basketball player. He knew how to play. He knew how to crawl inside the heads of the players he defended. He knew how to win.

And Seattle related to him.

He was the freckle-faced rogue on a team with multiple personalities. He was Huck Finn, always in the referees’ faces. Always tugging at an opponent as he fought through a screen. Always looking for an edge.

D.J. wasn’t a saint. That was part of his attraction.

He was stubborn, and his locker-room clashes with Silas were legendary. Wilkens finally traded him to Phoenix for Paul Westphal in one of the worst deals in league history.

And even as Wilkens was referring to D.J. as a “cancer,” real Sonics fans considered the trade a betrayal. It became part of the team’s great unraveling.

He was a meteor in Seattle, staying here only four seasons, but his mark is indelible. He was the MVP of the 1979 Finals. As he did with most coaches, he got the last word on Motta.

D.J. eventually was traded to Boston, won two championships there and played in epic playoff series against Atlanta and Detroit and, of course, the Los Angeles Lakers.

It is especially sad to think about him dying now as the franchise fights for its survival. He was one of us. He was part of Seattle, a guy who loved playing basketball for a city that loved him back.

His death recalls the Sonics’ rich history at a time when their future feels as uncertain as life.