Seahawks, Bears both defending Stevens

KIRKLAND, Wash. – There are two teams trying to defend Jerramy Stevens this week.

One is the Bears, whom Stevens will be opposing in the NFC divisional playoff game Sunday at Chicago.

“He is most certainly a concern,” Bears defensive coordinator Ron Rivera said.

Then there are the Seahawks, who employ him.

Mike Holmgren’s face reddened and his words became terse when asked what about Stevens has led him to stick with the bearded, heavily tattooed and talkative tight end through infamy and inconsistency.

Through now-distant alcohol troubles and arrests and jail time. Through dropped passes. A silly Super Bowl dustup last February. Two knee surgeries in four months this preseason. More dropped passes. And being a player so grating, that even teammates admit the rest of the NFL doesn’t like him.

“I want to be clear about this: You could probably say at one point in his life, the distraction issue comes into play,” Holmgren said, sternly. “In the last three years, that’s not part of the deal. He’s our best tight end. HE’S OUR BEST TIGHT END.”

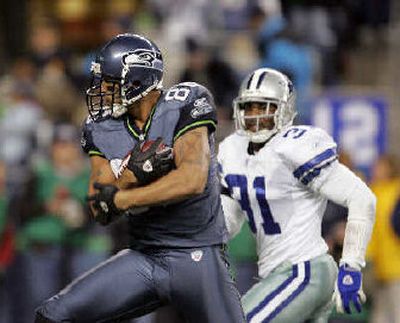

Seattle’s first-round pick in 2002 out of hometown Washington caught two touchdowns in last week’s 21-20 win over Dallas. He is the potential X factor in Seattle’s quest to win its first road playoff game since 1983.

He’s 6-foot-7 and 260 pounds, taller than the linebackers and safeties who usually try to outreach him for passes down the middle. He’s as fast as a wide receiver.

“Speed, size and ability to get open – he’s one of the best there is,” Chicago linebacker Hunter Hillenmeyer said.

That’s why the Seahawks support Stevens.

“He’s really gifted,” offensive coordinator Gil Haskell said. “And he’s very smooth. For a man that size, he’s like a basketball player being able to move and do those things.”

He’s so elusive, he declined to be interviewed both Wednesday and, after just a few words, again Thursday.

Seahawks running back Shaun Alexander, who like Stevens was injured and missed the 37-6 loss at Chicago on Oct. 1, spoke for him.

“Jerramy Stevens, he changes the game,” Alexander said.

After three underwhelming seasons, Stevens emerged with career highs of 45 catches and five touchdowns in 2005. He was a large reason Seattle reached its first Super Bowl.

But there, Stevens got in a verbal spat with Pittsburgh linebacker Joey Porter after Stevens said that while retiring Jerome Bettis’ Detroit homecoming was a nice story, the Seahawks were going to ensure the Steelers running back “a sad day when he leaves without that trophy.”

After impressively weathering what he called the “ridiculous” media circus his comments created, Stevens dropped three passes in a 21-10 loss to the Steelers.

Stevens missed the first five games of this season following surgeries on his left knee in April and August. Then, three games into his return, Oakland defensive end Tyler Brayton kneed Stevens in the groin late in a 16-0 Seahawks win.

The league fined Brayton $25,000 and Stevens $15,000 for the incident. Few believe Brayton went after Stevens because he didn’t like his tattoos.

“He reacted like any of you would have reacted if you were out there in a situation with this punk,” said Warren Sapp, Oakland’s outspoken defensive tackle.

Seahawks teammate Julian Peterson said he couldn’t stand Stevens when Peterson played in San Francisco prior to this season, because Stevens “knows how to rub people the wrong way.”

Then came a spate of more dropped passes and loud boos from hometown fans – before they cheered last Saturday’s take-that performance against the Cowboys.

“They’ve been doing that since I’ve been in high school, man. Ain’t nothing new,” said Stevens, a former prep quarterback from nearby Olympia.

His support system?

“Family, 100 (percent) man,” he said.

Holmgren’s been part of that. Coach and player share a unique relationship in which they trade playful teases and laughs through the ups and downs.

“It probably comes from my days of teaching in high school,” Holmgren said. “Kids … they come from all different backgrounds … you learn to try and understand them. Help them. Create a vision from them.”

When asked how much he appreciated Holmgren’s support, Stevens abruptly got up from his locker bench and said, “I’m done. I’m done for today.”

When Holmgren’s West Coast offense is playing at peak efficiency, which has rarely happened this season, its tight end is its trump card.

Seattle wants Alexander to run effectively enough to control the game and keep opposing pass rushers from focusing on quarterback Matt Hasselbeck. Then, Holmgren seeks to exploit opponents’ preoccupation with wide receivers Darrell Jackson, Deion Branch and Bobby Engram by sending Stevens down the middle on a mismatch with that poor linebacker or safety.

Seattle’s problem: Chicago doesn’t provide such a mismatch. It has All-Pro Brian Urlacher.

The 6-4, 258-pound former defensive back at New Mexico can just about look Stevens in the eyes. He is a quick and skilled ballhawk who often renders the tight end as quiet as Stevens was Thursday.

He’s also stingy in his admiration for Stevens.

“The tight end? What about him?” Urlacher said. “He played a good game last week, right? So. Yeah.

“We’re going to do what we do every week. We’re not going to double anyone. We’re not going to pay any special attention to anyone. If he beats us, then he beats us.

“We don’t change.”