Girls gone wild

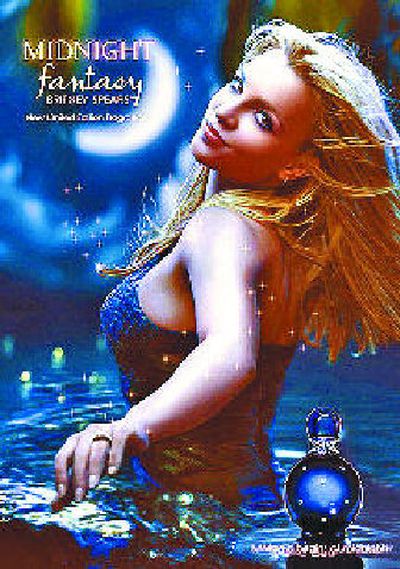

SACRAMENTO, Calif. – From advertisements to magazine covers, the image of the promiscuous girl is being celebrated. With her hit “Promiscuous,” singer Nelly Furtado sold more albums than ever once she sexed up her image. Party girls Paris and Britney forget underwear for a night out, and teen girls echo those images on their MySpace pages.

All this has caught the attention of parents, educators and authors, and it also has caught the attention of the American Psychological Association, which recently released a report called “The Sexualization of Girls.”

In the report, six female psychologists and educators argue that these images are damaging to girls’ self-image and mental health, teaching them to objectify themselves.

Anecdotal evidence is all over pop culture:

Bratz dolls, designed for 4-to-8-year-olds, flew off the shelves last year. The dolls are known for their sexy clothing – miniskirts, fishnet stockings and feather boas. But what concerns experts more is what the Bratz do – or, actually, what they don’t do.

“They’re marketed as a sexy, Paris Hilton version of teens,” says Lyn Mikel Brown, a professor of education at Colby College in Waterville, Maine, and author of “Packaging Girlhood” (St. Martin’s Press, $17.22, 336 pages).

Bratz are about fashion, shopping, clubbing and not much else, Brown says. But Boyz, their male counterparts, exit their boxes ready for action, equipped with soccer balls and skateboards.

Singer Fergie’s latest CD was listed by Amazon.com as one of the top 10 things “every teen girl wants for the holidays.”

The CD included the song “Fergalicious” – which peaked at No. 2 on Billboard’s Hot 100 singles chart – and included lyrics insisting that Fergie is not “easy,” “sleazy” or “promiscuous.”

Fergie sings those lyrics in her video while wearing a tiny Girl Scout uniform – a cropped, midriff-baring top and a short, pleated skirt. She also dons a bathing suit and rolls in cake, singing about how “delicious” she is.

Clothing stores for ‘tweens are increasingly selling sexy clothes, such as camisoles, lacy panties and thongs.

“Attitude” T-shirts are available for all ages, such as the Abercrombie and Fitch tees that a group of Pennsylvania teens “girlcotted.” Among the slogans were: “Blondes are Adored, Brunettes are Ignored” and “Who needs brains when you have these?”

A real-life crew of Bratz – Britney Spears, Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan – is currently more famous for partying than talent. Entertainment blogs and YouTube let us to follow their every move – rehab stints, DUIs and those nights when underwear just didn’t go with the outfit.

Educators argue that this cultural shift toward female sexualization is teaching girls to value their own sexiness as a commodity, as something that can be traded for power, money, popularity or winning the boys.

“It’s almost like sexualization keeps them in their place; it keeps them down,” says Tomi-Ann Roberts, one of the authors of the APA study and a professor of psychology at Colorado College. “It reminds you to stay an object of others’ admiration as opposed to a human being of competence.”

The sexy-is-powerful trend could be traced all the way back to the 19th century, but experts believe that in recent years, it seems to have stemmed from the “girl power” focus in the late ‘90s – the years of female empowerment programs for girls. The third-wave feminist movement introduced the notion that women could be into wearing pink high heels and still be powerful, successful and smart.

“Marketers picked up on the prettiness and left the real power stuff behind,” Brown says. “It’s sold as an image of power, but it’s not changing-the-world kind of power. It’s choosing between mango lip gloss and cherry lip gloss.”

The APA report links sexualization with three of the most common mental health problems of girls and women: eating disorders, low self-esteem and depression. Some of the negative consequences, according to the report, include:

“Constant comparison between one’s own body and cultural standards, leading to feelings of inadequacy and shame.

“A tendency to focus more on a partner’s judgments of one’s appearance than on one’s own desires, safety and pleasure.

“A significant jump in plastic surgery for teens between 2000 and 2005. Invasive cosmetic surgery increased 15 percent, and minimally invasive cosmetic procedures, such as botox injections, chemical peels or laser hair removal, increased 7 percent.

The most common procedures sought by teens are breast enlargements, nose and ear reshaping, and liposuction, according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons.

Brown’s research found that two types of girls are generally presented in the media: the girl who is for the boys, and the girl who is one of the boys.

Hallie McKnight, 15, of Carmichael, Calif., can attest to that. She attends an all-girls school where uniforms are required. But she knows girls who on weekends wear low-cut shirts and short skirts.

Hallie thinks it’s not because they like wearing those clothes.

“It’s for the guys,” she says.

Experts encourage girls and their parents who are concerned by this issue to voice their opinions. Last year, an attempt to create dolls in the likeness of the sexy singing group the Pussycat Dolls was pulled after parents protested.

And parents should discuss with daughters issues such as gender stereotypes and sexualization. Ask them why they like it, what’s attractive to them, and have a real conversation.

“They’re going to like music because it’s a great beat. Introduce them to the ways this rap song fits in a much bigger culture reality, helping them connect the dots,” Brown says.

Despite evidence that American culture is more sexualized, girls are doing well and may be more confident than ever before, says Deborah Tolman, another author of the APA report. She describes real confidence in one’s sexuality as something more than just focusing on other people’s perceptions of your appearance.

“It’s living in your own body, feeling entitled to your own body, feeling your body rather than thinking of your body as a commodity, an object to give and take,” Tolman says.

Experts say parents can help their daughters come to that way of thinking simply by talking about it.

Hallie and her mom, Laurie McKnight, have similar thoughts on the subject – they both say it’s hard to find clothes that aren’t overtly sexy in teen clothing stores.

McKnight, who also has a 12-year-old daughter, says she often discusses her opinions with her girls often.

“Your clothes say something about yourself,” McKnight says, “so why not say something positive about yourself?”