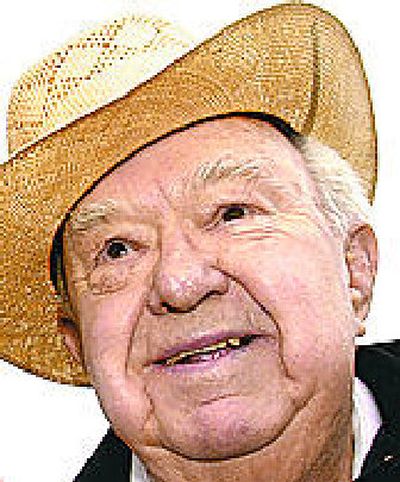

Les Schwab, retail tire icon, dies at 89

PRINEVILLE, Ore. – Les Schwab, a cowboy-hatted icon of Oregon who turned a dilapidated tire shop he bought in 1952 with borrowed money into a regional empire, died Friday at age 89, his company said.

Schwab, who had been in poor health in recent months, was very much a self-made son of Oregon’s High Desert. Funeral services will be private.

With his trademark hat and an ironclad policy that the customer rules, he built the run-down shop into a chain of 410 stores that did $1.6 billion in sales last year.

His tire shops with their red-and-yellow signs are fixtures in small communities, and some big ones, across the West.

“I never thought I’d do $1 million in sales, so I’ve been 1,000 times more successful than I ever thought I’d be,” Schwab, who was orphaned at age 15, said in 2003.

The privately held company employs 7,000 people and sells 6 million truck and car tires annually. It adds about 20 new stores a year and pays for them in cash, Schwab said.

The company said family members will continue to run it.

“There will never be another Les,” Phil Wick, chairman of Les Schwab Tire Centers, said in a statement. “He was a visionary, and all of us who worked with him will stay true to his vision of integrity, service and treating people right.”

Until about a decade ago, Schwab appeared in nearly every commercial for his company, making him one of the best-known faces in the West and fixing himself in the region’s collective consciousness.

Employees wear their hair above the collar and sprint to customers’ cars when they pull in.

“They are known for their service, and dealers from around the United States will travel to Les’ stores to see how he does business,” said Bob Ulrich, editor of the Modern Tire Dealer.

“Superb customer service is the key and Les just happens to be better at it than anyone else.”

His profit-sharing program put 55 percent of profits – or more than $60 million – in employees’ pockets in 2002, which encouraged worker loyalty. And Schwab liked to promote employees from within.

“Why wouldn’t you work for him? You’ve got to work hard, but what if you were guaranteed to retire wealthy?” Ulrich said. “His profit-sharing is a great program, and it’s rare.”

Schwab carefully cultivated the laid-back, cowboy image of rural Oregon.

In 1963, he started the “Free Beef in February” promotion to boost sales during the slow winter months. Customers who buy four tires still get $15 in free beef and customers who buy two get half that.

He spent roughly $1 million a year doing it and another $1 million advertising the fact.

Every Les Schwab store rents a freezer for a month, he said.

Schwab’s success came the hard way.

Born on a hardscrabble homestead in Crook County near Bend, he grew up in a two-room shack at a nearby logging camp, where he attended grade school in a converted boxcar with “crooked windows cut in the side.”

His mother died of pneumonia when he was 15 and his father, an alcoholic, was found dead in front of a bar just before Schwab’s 16th birthday.

An aunt and uncle offered to take him in but he rented a room at a Bend boarding house for $15 a month and delivered newspapers for the Oregon Journal while struggling to finish high school.

He got the coveted downtown delivery route and added another, and at 17 was making $200 a month, about $65 more than his high school principal, and owned the only new car at school, a Chevrolet two-door sedan.

After graduation he married his high school sweetheart, Dorothy Harlan, and continued selling newspapers full-time. At 25, he took a job as circulation manager of the Bend Bulletin, but wanted to try something more lucrative.

He borrowed $11,000 from his brother-in-law in 1952, sold his house and borrowed on his life insurance policy. He walked away with O.K. Rubber Welders, a dilapidated tire franchise with no running water and an outdoor toilet. He knew nothing of tires and had no formal business training.

But by the end of the first year, Schwab had done $150,000 in business, five times more than its previous owner – and by 1955 he had opened four more stores, two under the name “Les Schwab Tire Centers.”

Schwab eventually handed off most day-to-day duties, but until his health failed, most days would still find him in his office reviewing financial records, lunching with his top management at the local country club or tapping out a monthly column for the employee newsletter.

“Most tire dealers admire Les Schwab for what he’s accomplished, with special kudos for doing it his way,” said Bruce Davis, special projects reporter for tirebusiness.com. “He has carved out his own identity.”

Les and Dorothy Schwab had two children. A son, Harlan, was killed in an auto accident in 1971. A daughter, Margaret Denton, died last year of cancer at 53.