John Blanchette: Misunderstood Russell always had it figured out

Not every athletic giant is a cultural giant, but most of the enduring ones are – the ones who didn’t need to be reminded that there was a big old universe that started on the other side of the arena exits.

So it’s revealing that in the “Sports: Breaking Records, Breaking Barriers” exhibit now in town at the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, exactly five of the more than 30 featured athletes were born after 1970 – and none of them sprouted in the big-buck, mainstream games of baseball, football or basketball.

Revealing? Some would say damning.

But not that old contrarian, Bill Russell.

The current consensus is that the modern athlete is self-absorbed and socially unconscious – that they will continue to break records (see: Bonds, Barry) without breaking much of a sweat for a cause (see: Woods, Tiger). The activist athletes of the past – Jackie Robinson, Jim Brown, Billie Jean King, Curt Flood, Bill Bradley and, yes, Bill Russell – have given way to a generation of sinewy corporations, more mindful of how their political stands might play with fans and sponsors.

Yet there is something about this conclusion that Russell finds to be dishonest.

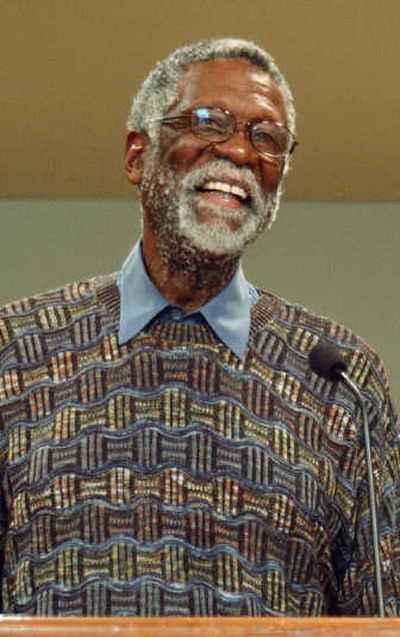

The basketball legend – the game’s greatest winner – comes to Spokane on Saturday for a sold-out speech at the MAC in his role as spokesman for and participant in the Smithsonian’s touring exhibit. It figures to be provocative, absorbing and possibly unsettling; at 73, Russ continues to resist easy dogmas.

“I was talking to Kareem (Abdul-Jabbar) once,” Russell said in a telephone interview this week, “and I asked him how old he was the first time an adult said to him, ‘It’s really important you play well this next game.’ He said he was 12. Well, from 12 on, they’ve eliminated his adolescence. And the people who intruded on his adolescence had their own agenda, not necessarily for his benefit. And kids aren’t naïve. They see what’s happening to them.

“Kids are a product of their society. If you were to get together all the prodigies of all the other fields, you would find the behavior identical – regardless of culture, race, religion. To expect them to act different … I don’t think you’ve ever heard me criticize any of the modern athletes, no matter who they are.”

Yet the MAC exhibit clearly was put together – with input from Russell, among others – with an eye on athletes and innovators who made a difference socially.

That might mean in a humanitarian sense, like Roberto Clemente, or something less substantial – like heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan, billed as “America’s first national sports celebrity.”

Pinning down Russell as to his role, however, is problematic.

He recalled a long airport layover during his playing days with the Boston Celtics when a series of strangers approached him to comment on his height (“an astute observation,” he cracked) and ask if he was a basketball player.

Every time, the answer was no. Finally, teammate John Havlicek wondered why Russell didn’t own up to it.

“That’s what I do, not what I am,” he told Havlicek. “I’m a man. My profession is basketball.”

He played it for himself, his teammates and the soul of the game, and for no other reason.

“My daughter asked me one time how I handled the boos,” Russell said. “I told her, ‘If you don’t accept the cheers, you don’t have to accept the boos.’”

Or the boos directed elsewhere.

Of the athletes featured in the exhibit, 12 rose to fame in team sports – but none found himself forever linked in public debate over their relative worth the way Russell did with Wilt Chamberlain, who got the worst of it for the simple reason that his teams never won like Russell’s Celtics.

Again, Russell does not reflexively warm to that criticism.

“We were not rivals,” he insisted. “In a rivalry, there’s a victor and a vanquished, and in our careers we were both very victorious. His philosophy – and it was pretty sound – was that he was the greatest basketball player and greatest force in sports. And if he went out and used his skills to the best of his ability and worked as hard as he could, they should win the games. Every game, he’d have to change jerseys at halftime because he’d have 4 or 5 pounds of sweat in the one he used in the first half. Every game.

“He was the best I ever played against – not even close. And I told him in the last year he was alive, ‘Wilt, I’m the only person on this planet who really knows how good you are.’ “

The Bill Russell of popular legend – difficult, thorny – is being seen somewhat differently these days, though of course he would contend that’s mere perception and that he hasn’t changed.

But he did accept an honorary degree from Harvard this year, and he agreed to speak on behalf of this touring exhibit.

And believe it or not, he even hosted his own fantasy camp – one-time-only, at a top-dollar price of $15,000. He confessed to selfish motives – he wanted to hang out with close friends like Havlicek and Oscar Robertson, who served as counselors.

“It’s that we all understand what we’re talking about,” he said. “Fans in particular and sometimes coaches don’t have any idea what’s going on in the mind of great athletes while they’re performing. My coach, Red Auerbach, was the greatest in history. At the end of my rookie season, he told me, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing, but it’s working and I’m not going to mess with it.’ “

Criticism, analysis, guesswork – in the end, it all says more about the critic, analyst or guesser than the subject.

“It is far more important to understand,” said Bill Russell, “than to be understood.”