Senate efforts brought home millions

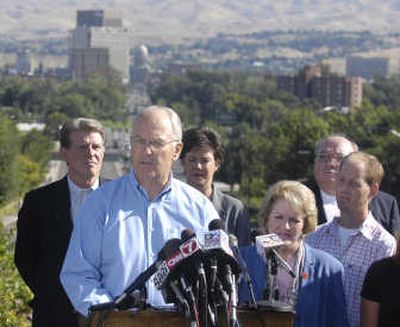

BOISE – Idaho Sen. Larry Craig, a 62-year-old Republican raised on a dusty ranch near Midvale in southwestern Idaho, built his career based on firm stands in favor of traditional resource industries, gun rights and a balanced budget amendment, rather than on the force of his personality.

It’s a long, consistent career that backers are sorry and surprised to see cut short by a sex-solicitation scandal.

“Larry Craig’s done some wonderful things for Idaho, and I’m afraid that this one incident will be what he’s remembered for rather than all those good things,” said Sen. John Goedde, R-Coeur d’Alene.

Conservative on social issues, Craig was an advocate adoptive parents rights, a champion debater, and was best known for the Craig-Wyden legislation, in which he worked with Oregon Democrat Ron Wyden to preserve millions in federal funding for rural communities and schools hard-hit by downturns in logging on federal land.

“In county circles, they’ll all say ‘Craig-Wyden’ – you’re supposed to know; that’s all they say,” said Jim Weatherby, Boise State University political scientist emeritus and an observer of Craig since his days at the University of Idaho.

“You just can’t forget all the good that he’s done,” said state Rep. Marge Chadderdon, R-Coeur d’Alene.

The senator, known for his lecturing tone, was noted for bringing home millions in research funds for universities and most recently has drawn criticism and praise for his controversial leadership in immigration reform efforts, rooted in his concern for Idaho agriculture interests.

“I think Craig understood the dilemma of growers and ag about where do you get the people to do the harvesting you need, the backbreaking stuff?” said John Freemuth, a BSU political scientist who studies public lands and resource issues. “Larry Craig is still very close to ag and the needs and struggles of those folks.”

Even Craig’s enemies say he’s smart. The University of Idaho grad – he was student body president – did graduate work at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., before returning to work in the family ranching business, which later went bankrupt.

He was elected to the state Senate three times starting in 1974 and was known as a skilled debater and an “independent thinker,” said Randy Stapilus, who worked as an Idaho political reporter for years and wrote several books on the state’s political history.

“I would listen on the speakers to Senate floor activity, and when Craig came on, my first initial response was, ‘Oh, is Frank Church in town today?’ ” Stapilus recalled, referring to the Idaho Democratic senator, presidential candidate and noted orator. “There was a real similarity in their voice and style.”

When Craig ran for the 1st District congressional seat in 1980, his positions sounded much more conservative. “His message sounded rather abruptly very much like that of Steve Symms, who of course he was running to replace,” Stapilus said. “For those of us covering him at the time, that was certainly a major change.”

It stayed that way ever since. Craig made his mark as a consistent conservative, opposing tax increases, pushing for a balanced budget amendment – which he came within one vote of winning – and earning the ire of environmental groups for his down-the-line support for resource industries, which have been major campaign contributors.

Longstanding rumors that the married senator might be gay stem from a 1982 congressional page scandal, in which Craig, then a bachelor, was the only member of Congress to issue a pre-emptive denial of involvement. No member had been named at the time.

The next year, he married Suzanne and adopted her three children. They’ve been married 24 years.

Craig served five terms in the House, then ran for the U.S. Senate in 1990 to replace retiring Sen. Jim McClure. His long Washington tenure, consistency and advocacy helped him build clout, and he rose in 1996 to the No. 4 position in Senate GOP leadership as chairman of the Republican Policy Committee. Craig boasted in 2002 that his role made him a “conservative critic,” and he took pleasure in firing off GOP position papers declaring Senate Democrats’ policies “dysfunctional.”

He also cherished the formal collegiality of the Senate, however, and as his career progressed became more willing to reach across party lines. He partnered with Wyden in 2000 to write and pass the Craig-Wyden bill, which sent millions in payments to rural, timber-dependent counties each year. Once it expired after five years, rural communities and states have pushed hard each year to extend it.

Craig also earned a reputation for getting things done, whether securing millions in university research funds or slipping a rider into a bill to eliminate a salmon agency he disliked. His office says he’s secured more than $122.4 million for research at Idaho universities since 2002.

Craig became chairman of the Senate Special Committee on Aging in 2000, a post he gave up in 2004 to become chairman of the Veterans Affairs Committee. In that spot, he successfully pushed for new VA outpatient clinics in Caldwell, Lewiston and Coeur d’Alene.

Though he’s long been seen as secure in office, Craig took very seriously challenges from millionaire Democrats Walt Minnick in 1996 and Alan Blinken in 2002, running hard to hold his seat.

On social issues, including gay rights, he has followed a conservative path. He voted repeatedly to ban same-sex marriage, and last year issued a statement in support of Idaho’s constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage and civil unions. He also voted against two measures in 1993 to ease the treatment of gays in the military; voted against 1996 legislation to extend employment discrimination laws to cover sexual orientation; and opposed a 2002 proposal to add sexual orientation to the federal hate crimes law.

As he considered whether to run for another term, Craig was taking a beating in Idaho over his stand on immigration reform. Two weeks ago, he offered this rather academic explanation for his views to The Spokesman-Review’s editorial board:

America’s economy relies on growth to keep it on an even keel. “We’ve been able to sustain at or around a 3 percent economy in the Bush years,” he said. But Americans have only 2.1 children per woman of childbearing age – a break-even level. “As the boomers leave the market … 24 million Americans will be leaving the work force.” More workers will be needed, he said, “at a time when our birth rate is declining. Historically, we have sustained our economies by sensible immigration.”

Craig cites poorly written immigration laws, which he attributes to union interests that wanted to protect members’ jobs, that proved unworkable. As a result, millions of illegal immigrants hold U.S. jobs.

Craig said many of those workers will be displaced as the nation cracks down on illegal immigrants. As a result, he said, “we’ll lose about $6 billion this year” in farm crops, including some that will rot in the fields. “You’re paying about a dollar more for orange juice because of that … so it’s hitting the consumer.”

Craig said his worst fear is that farmers will move their operations south of the border because they can’t find enough workers here. “That’s simply the wrong thing to do, we ought to get it corrected,” he said. “Americans are angry, they’re frustrated by it. … It’s a matter of creating a legal system, it’s a matter of controlling borders and access.”

His stance has made enemies among anti-immigration activists in Idaho and elsewhere, though Craig says he never has supported tolerating illegal immigration.

“I’m the guy that went to the president a year and a half ago and said, ‘Mr. President, declare a national emergency, nationalize the Guard and close the southern border.’ He didn’t quite do it that way,” Craig said.

He warned that immigration is a problem that must be fixed. “We ought to be smart enough to do it,” he said. “We’re going to get there. If we don’t get there this year, we won’t get there ‘til 2009, after the presidential election. … But we have to get there or our economy will start dying.”

If Craig had sought and served another term in the Senate – something he had equivocated about for months – his longevity would have matched that of Idaho’s legendary Sen. William E. Borah, who served from 1907 until his death in 1940.

Northwest Nazarene University political scientist Steve Shaw said, “There’s a lot you can get done in a lengthy political career, and then one stupid mistake kind of defines you.”

Craig’s arrest and guilty plea to disorderly conduct in an airport men’s room sex-solicitation case brought condemnation from his own party leaders in the Senate, who called for an ethics investigation and stripped Craig of his ranking Republican status on three key committees last week.

“While it may not overshadow or replace his accomplishments, it just tarnishes it so badly,” Shaw said.

It’s unclear what Craig will do next. His latest Senate financial disclosure form shows he has little to no income beyond his $165,200 per year Senate salary, though his long service will qualify him for a retirement pension.

“Thirty years he’s served the people, he’s never made any money,” said Jasper LiCalzi, a political scientist at Albertson College of Idaho. “He’s always been in public service, so he’s not a wealthy man or anything.”

Weatherby said, “Politics has been almost his whole adult life. And to go down as he’s done here is just devastating. How quickly he fell, with very little to break the fall.”