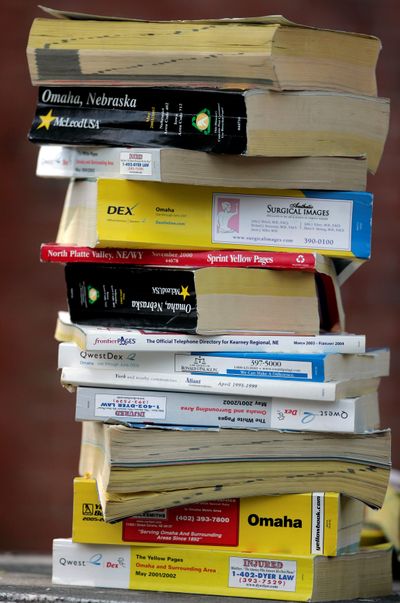

Weighty issue

As phone books multiply, so do consumer hang-ups

ALBANY, N.Y. – It’s been a fixture on kitchen counters, refrigerator tops and junk drawers for decades.

But today, the Yellow Pages is a bit too ubiquitous for some, with phone books published annually in the U.S. outnumbering the population by two to one.

While the $17 billion-a-year industry is showing remarkable resilience as other advertising-driven businesses suffer, it has become a familiar target in state legislatures, where lawmakers have tried – unsuccessfully, so far – to place limits on the distribution of phone books.

The Yellow Pages Association, an industry trade group, calls 2008 the industry’s “most challenging year to date with regard to efforts at the state level to restrict directory publishers’ ability to freely deliver phone books.” Recent legislation that would empower residents to opt out of receiving phone books has failed or stalled in at least seven states.

The association has paid lobbyists about $50,000 so far this year to defend it in communities across the country. Two main points the group tries to get across are that phone books help promote local businesses and that they are made almost entirely from wood scraps collected at saw mills and recycled paper.

In Albany, city councilman Joseph Igoe is trying to build support for a law that would limit the distribution of phone books and require publishers to make it easy for people to halt delivery. Igoe said the issue came to his attention while campaigning door-to-door last spring and saw phone books wrapped in plastic littering sidewalks, driveways and lawns.

If Igoe succeeds in passing legislation, it will be noteworthy. Proposals have been floated – without success – by state legislatures in Alaska, Hawaii, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina and Washington.

Some residents in Seattle and other communities in King County, Wash., receive phone books from as many as four different publishers, said Tom Watson, a waste prevention specialist for the region. “There hasn’t been a good way to opt out,” he said.

Phone book publishers acknowledge that many households and businesses receive more phone directories than they need. But they call it a sign of competition in a healthy business and argue that the marketplace, not the government, should determine the number of phone books distributed.

For years, phone companies dominated the directory business and published the only phone book available in many markets. Federal rules enacted in the late 1990s required phone companies to provide listings to independent publishers at a reasonable cost and ignited an explosion of competition.

Last year, Yellow Pages publishers logged roughly $16.8 billion in revenue. That figure is on pace to rise to $17.2 billion this year, and $17.6 billion in 2009, according to Simba’s projections.

Yellow Pages Association spokeswoman Stephanie Hobbs said most of the country’s 200-plus Yellow Pages publishers already allow people to opt out from receiving the books by phone, mail or online and provide recycling when they become outdated.

Skeptics, however, say phone book publishers don’t always make it obvious or easy to opt out and the cost of blanketing neighborhoods with books they know will be discarded is cheaper than targeting distribution.

YellowBook’s Walsh – whose company has acquired 60 smaller publishers in recent years – thinks the problem will likely sort itself out as the Yellow-Pages business continues to consolidate. Most markets don’t sustain phone books from three or more publishers for very long, he said.