Casting for fishing’s future

He’s hobnobbed with presidents. His likeness hangs alongside those of Ernest Hemingway and Zane Gray in the Sport Fishing Hall of Fame.

He’s been “up to his armpits” in mud working to improve salmon habitat, and now he’s up to his eyebrows in politics, having concluded that therein lies the only hope of saving his beloved salmon and steelhead.

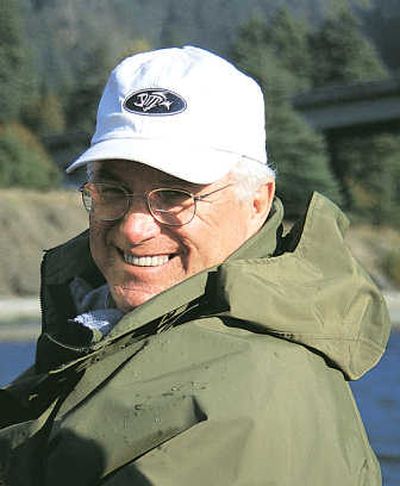

He’s Gary Loomis, a white-haired, 66-year-old dynamo whose smiling likeness recently graced the cover of Outdoor Life Magazine, which named him one of 25 “People Who Have Changed the Face of Hunting & Fishing.”

If his name sounds familiar, it may be because it’s printed on some of your fishing gear. A machinist by trade and an angler by avocation, Loomis helped pioneer modern carbon-graphite rod technology. In 1982, he started G. Loomis, Inc., which became a leading producer of high-performance fishing rods.

Or the familiarity might stem from the fact Loomis, who lives in Woodland, Wash., has been criss-crossing the Pacific Northwest in recent months helping organize local chapters of the Coastal Conservation Association, the largest sportfishing advocacy group in the U.S.

Formed 30 years ago along the Gulf Coast, the nonprofit CCA bills itself as a “grassroots organization dedicated to the conservation, promotion and enhancement of the marine resources of the United States.” It claims more than 94,000 members in 17 state chapters along the Gulf, Atlantic and Pacific coasts.

Loomis is promoting the CCA with the determination of a striped bass chasing a steelhead smolt. He’s chairman of both the Oregon and Washington chapters of the CCA’s new Pacific Northwest division, and has been invited by the governor of Idaho to launch a chapter in that state.

“The plight of salmon is really motivating people by the hundreds to get involved in CCA,” said David Cummins, CCA president, noting that Loomis has been tireless in spreading the message, and he has the visibility and charisma to draw attention to this issue. “We have rarely seen this degree of frustration with a fishery and its management. People here know what is at stake.”

And Loomis has been hooking up lots of members. Since convincing CCA’s leadership to create a Pacific Northwest division in March, he’s helped launch local chapters in six Oregon and five Washington communities. Nearly 3,000 anglers so far have paid the $25 annual membership fee to join CCA.

His goal is ten times that many members.

Only the prospect of thousands of votes going against them, Loomis said, will force politicians and resource managers to do the best thing for salmon and steelhead, which is to stop the indiscriminate harvest of wild fish.

Recently in Eugene, Ore., Loomis likened the Coastal Conservation Association to the National Rifle Association. It’s the NRA’s political clout — “not the Second Amendment” — that allows Americans to have guns in their homes today, he said.

“Folks, there’s 1,900,000 fishing licenses sold in Oregon, Washington and Idaho,” Loomis said. “If we had 3 or 4 percent of that … we could get ‘em to listen to what we need, and that’s save our resource before it disappears.”

Politicians don’t listen to fishermen now “because we’re just one vote and because we’d rather sit and argue about barbed hooks against barbless hooks, wild fish against native fish or two fish in the limit instead of three in the limit” rather than engaging the political process, he said.

“I call Gary ‘the best Pied Piper we could ever have,’” said Stan Steele, a retired Oregon State Police game law officer who’s putting in 75 hours a week as CCA’s volunteer legislative coordinator in Oregon.

“Without him as a driving force, I know a lot of people would not have jumped aboard — it took a name with a reputation to really get this rolling,” said Mark Seghetti, owner of Steelheaders West tackle shop and president of the local CCA chapter.

Loomis sold his company to Shimano in 1997, and by then had begun focusing his efforts on “giving something back” to the rivers of his native state.

He founded Fish First, an organization whose goal was “More and better fish in the Lewis River with no politics.” Loomis and his fellow volunteers took Cedar Creek, a Lewis River tributary that state fishery managers had written off as “dead” and brought it back to life by replacing culverts, improving in-stream habitat, and using “egg boxes” and net pens to provide near-natural fry production and rearing.

But the real key was when Loomis — on the advice of a Canadian fishery expert — got salmon carcasses from the local hatchery and placed them in the streams to provide more nutrients for the juvenile fish.

The Canadian said, “‘Don’t you know that 87 percent of the body mass of a smolt leaving fresh water is made up of nutrients from the carcasses of the adults that spawned it?’” Loomis said. “My babies were starving.”

With the first-year class supplemented by carcasses, returns jumped from about 15 fish per year in each tributary of Cedar Creek to 250 to 450 salmon in each.

From 32 salmon in 1992, Fish First built the Cedar Creek run to 16,000 in 2002 — and looked forward to a projected return of the 30,000 in 2003.

“Instead of getting 30,000, we got 6,100,” Loomis said. State fishery managers decided to allow a gillnet season in the Columbia River — after most of the early-run fish produced by hatcheries had already passed and just as Fish First’s naturally produced coho were returning.

“These are endangered fish. These are on the Endangered Species List in the Columbia River,” Loomis said. “And they decided the commercial fishermen should get a 30 percent ‘incidental kill.’ And then they give them an extension with another 15 percent.”

After seeing 10 years of hard labor negated by a 10-minute decision and a 10-day gillnet season, Loomis said he realized “I’ll never be able to raise more fish than the commercial fisherman can harvest.”

His research convinced him that 80 percent or more of the region’s salmon were being harvested in the ocean.

Anglers have “been brainwashed over the years” into thinking that the problem with salmon and steelhead is caused mostly by “hydro (dams), habitat and hatcheries,” Loomis said. But the main problem is the overharvest of wild fish.

The Coastal Conservation Association is the only angler organization in the U.S. that has a track record of real success fighting overharvest the ocean, Loomis said.

The CCA’s success is based on casting votes rather than lures. And Loomis seems at ease carrying the conservation message to the highest political levels.

In August, Loomis spent several hours talking fishing with George Herbert Walker Bush and giving the former president fly-casting tips on the lawn of Bush’s home in Kennebunkport, Maine. Loomis had been invited there to participate in the filming of a CCA documentary on salmon in the Northwest, for which Bush was being interviewed.