Speaking in Salish

“way’ sl’axt.” Hello, friend.

Little by little, small groups of students are learning this simple phrase – and many more – in Salish, the language of American Indian tribes such as the Kalispel, Spokane, Colville and Coeur d’Alene.

Salish is a disappearing language, with maybe 50 fluent speakers living among Colville Confederated Tribe members in the United States, said LaRae Wiley, who teaches Salish for Eastern Washington University. An enrolled member of the Arrow Lakes Band of the Colvilles, Wiley is currently teaching an evening class of 10 students at Havermale High School in Spokane.

Those students range in age from 16 to 61 – Running Start high school students, EWU students and a few community members wanting to learn the language.

Donna Brisbois-Burke, the oldest of the students and an enrolled Spokane tribal member, said, “I’m getting older, and I don’t want to die without learning my own language and more about my own culture.”

Trina Ray, an Okanogan band Colville, had been relocated and sent away to school as a child, part of the now-discredited system of separating Native children from their families, and then adopted. “The language is being lost,” she said. “I felt bad not knowing my own language.”

Wiley, whose grandmother was the last fluent Salish speaker in her family, spent two years in Keremeos, B.C., a few years ago in an immersion experience with Similkameen elder Sarah Peterson to become fluent in the language herself.

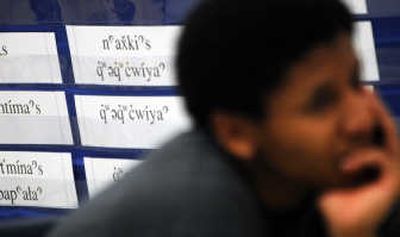

She recognizes that the language can be a challenge for a couple of reasons – as a predominantly oral language, it relies on the International Phonetic Alphabet, “which can scare some students. Also, there is a sad history of the language, how students were forbidden to speak it at the boarding schools, and that can make some people afraid to try it.”

Wiley, an EWU adjunct professor who is known in the region as a singer and musician with two CDs on the market, is passionate about the language as a cultural connection for Native people.

“Each language brings something original in how its speakers think about the world,” she said. “This is our native language. There are unique things you can say in Salish that you just can’t say in any other language. These differences are beautiful.”

Wiley and her husband, Christopher Parkin, have partnered with Sarah Peterson, executive director of the Paul Creek Language Association in British Columbia, in the creation of the center for Interior Salish, a nonprofit group that supports the language of the plateau Salish speakers (coastal Salish is an entirely different language).

“Sarah is the best transcriber of the language that I know in the whole Pacific Northwest,” Wiley said.

They have developed a three-level curriculum with reading materials and CDs. It is being used in British Columbia immersion schools and now in the Colville Tribal Head Start program and with the Kalispel tribe in Montana. They also will be conducting an immersion camp through EWU at Pascal Sherman Indian School in Omak, Wash., from July 7 to Aug. 22, designed for educators.

The center (www.interiorsalish.com) received a master apprentice grant from the Washington State Arts Commission to develop a traditional story-telling program for children, which took place last summer at Stevens County Library system facilities. It also received a 2007-2008 Potlatch Fund artist development grant to develop an original CD of Nsalxein (Colville-Okanogan) songs and is expected to be released in conjunction with a benefit concert in Spokane in June. Wiley will appear with Jim Boyd, an American Indian musician who performs often in the Northwest and whose music has appeared in such films as Sherman Alexie’s “Smoke Signals.”

The date and location of the concert are to be determined. Its proceeds will support bringing tribal elders to the summer immersion camp and to help pay a teacher for a planned preschool center to be established in the region. Concert information will be available at lwiley@interiorsalish.com

While all of this is in the works, Wiley continues her focus on teaching Salish in her evening classes and traveling to Canada to record music with elders. Recently, after her class sang “Happy Birthday” in Salish to Trina Ray, Okanogan elder Glen Douglas, 81, spoke in English and Salish to the students, telling a nuanced and culturally complex creation story and linking it to the history of Indians up through today.

Language and land are what are important for a people’s identity, Douglas said: “I would like to see this room filled up, but if we keep telling the stories, it will help the language to come back.”

That, and the efforts of people like Wiley who are so passionate about making it happen.