Out of the ashes

NEW YORK – The sign in the lobby of the Blender Theater, where James Frey is opening his once-unthinkable book tour, reads “NO RE-ENTRY. All exits are final.”

For the author of “A Million Little Pieces,” that’s simply another story in need of a disclaimer.

Two years after his addiction memoir was exposed as substantially fabricated and the author sent to a real-life version of a remainder bin, Frey, 38, is back in stores and back on stage.

He has written a novel, “Bright Shiny Morning,” released by a major publisher (HarperCollins), represented by a respected agent (Eric Simonoff), praised highly by The New York Times and among the top 20 sellers on Amazon.com and BarnesandNoble.com.

His comeback may be proof that publishing is helplessly naive, nobly forgiving or desperate for attention.

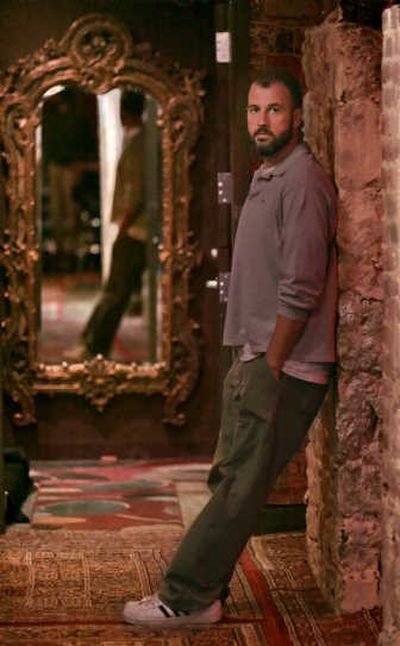

“I’ll bet you didn’t think you’d see me again,” the bearded, dark-eyed Frey, seated on a stool under a white spotlight, told the Blender audience last week.

The evening was an 80-minute, multimedia variety show with Frey as the finale. He read a passage about a gun dealer who despises equally all races and creeds, speaking to the heartbeat-rhythms of a jazz pianist as a slideshow of firearms flashed behind him.

In an interview earlier that day, the broad-shouldered, solidly built Frey is friendly, self-effacing and careful.

Citing a confidentiality agreement with the publisher of “Million Little Pieces,” he declines to answer several questions about the book and about memoirs in general.

Asked if he thinks memoirs should be fact-checked, he laughs and shakes his head: “I’m not going to go near that.”

“Bright Shiny Morning” is a 500-page, panoramic take on Los Angeles, written in the profane, hard-boiled, semi-grammatical prose of “Million Little Pieces.”

It has a first printing of 350,000, and critics on opposite ends of the country debating whether the novel is genius or junk.

David A. Ulin of The Los Angeles Times called it “a terrible book. One of the worst I’ve ever read” and “an execrable novel, a literary train wreck without even the good grace to be entertaining.”

Janet Maslin of The New York Times praised Frey as a “furiously good storyteller” and likened the book to the fabled return of a disgraced athlete: “He stepped up to the plate and hit one out of the park.”

Frey’s reaction to his downfall has alternated between defiance and shame. He has vowed never to speak to the press, but continues to do so (out of courtesy to his publisher, he says). He has complained that he was subject to undue scrutiny, that memoirs have traditionally been unreliable.

Today, he blames only himself.

“I don’t think of myself as a victim of anything,” Frey says. “I made some big mistakes and I know that. I’ve apologized for it, and I’ve tried to do my best to learn from it and move on from it.”

He calls the past two years “profoundly humbling,” but his ambitions remain high.

“I want to write books that change people’s lives,” he says, “change the way they read and write and think and feel, and hopefully change them for the better in some way.”

“A Million Little Pieces” was a best-seller when first published, then a sensation two years later after Oprah Winfrey chose it for her book club.

Frey has said he first wrote it as a novel and was turned down 17 times, until Doubleday Books suggested it be released as a memoir. His publisher at the time, Nan Talese, remembers it differently.

“It was originally submitted to me as nonfiction and I never thought of it as anything but,” Talese says, adding that his then-agent, Kassie Evashevski, and then-editor, Sean McDonald, agreed.

Doubts were raised early about the book, but Frey repeatedly, insistently said it was true, even to Winfrey.

But in January 2006, the investigative Web site The Smoking Gun released a long expose that revealed numerous fabrications, notably that Frey had never served four months in jail.

As the public and Winfrey turned against him, he confessed. Readers sued him for fraud. Frey was dropped by his agent and by the publisher that was to have released “Bright Shiny Morning,” Riverhead Books.

He was seemingly finished – seemingly.

Even discredited, the book sold, 1,000 or more copies a week. A court agreement that offered refunds for unhappy customers led to less than 2,000 requests.

One fan at the Blender Theater, 20-year-old Sarah Koenig-Plonskier, said she had read “A Million Little Pieces” at least 20 times.

“At first I was upset when he heard that he made things up, but when I went back and read the book again, I still had the same feelings,” she said. “The book touched me deep in my soul.”

Frey befriended HarperCollins publisher Jonathan Burnham after meeting him at a party, and also got to know literary agent Eric Simonoff, who says he “liked (Frey) enormously when I met him in January 2007, but told him it would all depend on the book.

“Then I read ‘Bright Shiny Morning’ and simply loved it,” says Simonoff, whose other clients include the Pulitzer Prize-winning fiction writers Edward P. Jones and Jhumpa Lahiri.

Frey says he plans to write another novel, about a Jewish man who has an accident and becomes convinced he’s the Messiah.

Married, with a 3-year-old daughter, he says he enjoys hanging out with people of all kinds, whether the Hell’s Angels providing security for his tour or members of the art community, where the lines between right and wrong helpfully blur.

“The art world is a place that’s always looking forward, always seeking out new ways to create work and present work,” Frey says.

“There are no rules in the art world. Whatever you do is acceptable. There are many more rules one has to follow in publishing.”