Retiring college leaders share the wisdom of their years

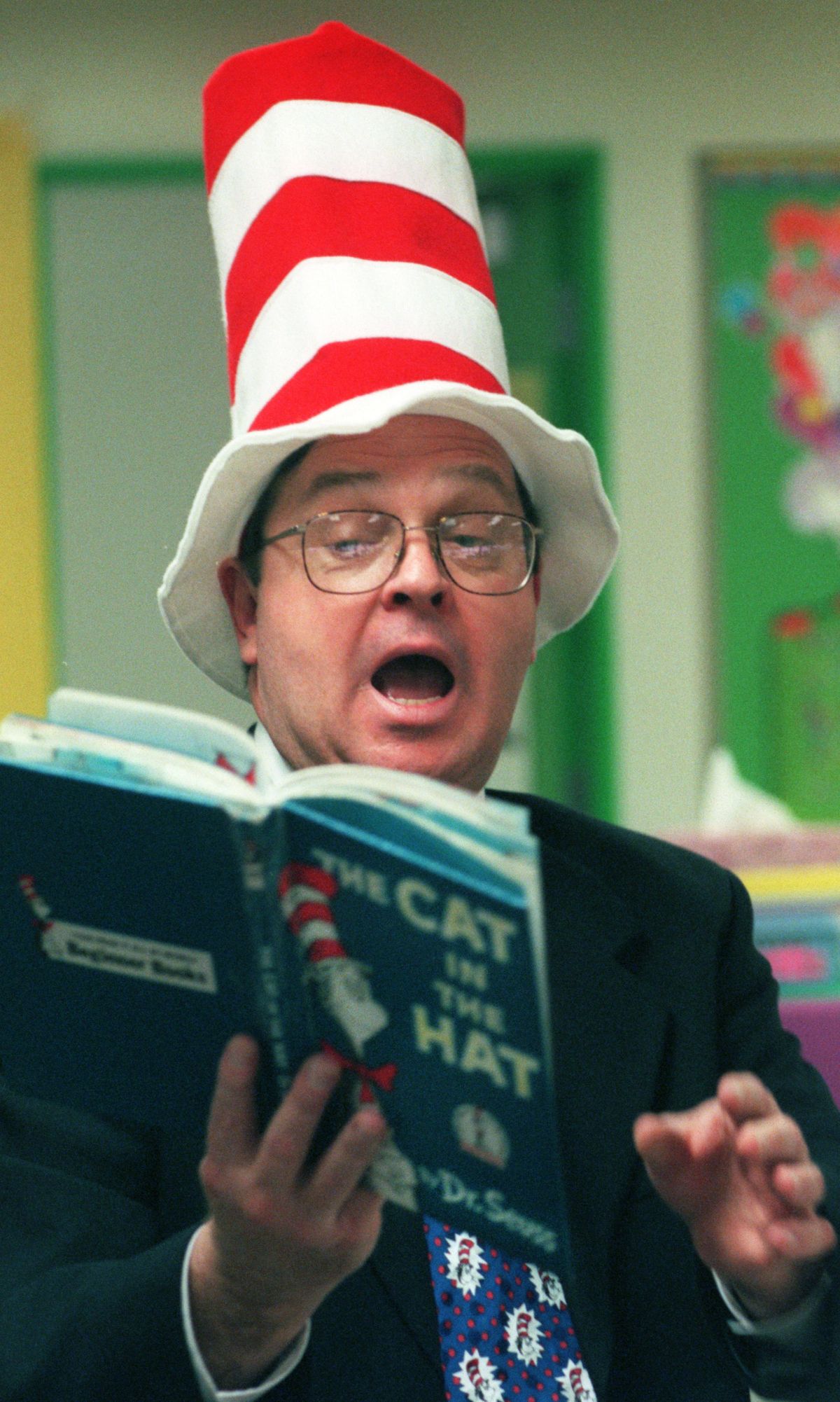

Dr. Gary Livingston belts out an inspired version of “The Cat in the Hat” to a class at Bemiss Elementary School in 1999.

Bill Robinson, president of Whitworth University, and Gary Livingston, chancellor of the Community Colleges of Spokane, will hand out college diplomas for the last time this graduation season.

Both feel good about their decisions to retire. Livingston, 62, plans to travel with his wife, Amanda, and remain active on several Inland Northwest boards. Robinson, 60, plans to do consulting work, write another book and stay on some boards, including the Princeton Seminary board. Both men will remain in Spokane.

On Wednesday, Livingston and Robinson will share the stage at the Our Kids: Our Business Capstone Luncheon. The men will talk about how to grow children into healthy adults.

In recent interviews, they shared some of their insights.

Every child needs a caring adult

“I’d start there,” Robinson said. “Make sure every kid has a grown-up who just flat-out unconditionally loves the kid. It’s best if it’s a parent, but it doesn’t have to be. I’m thinking of one student whose mother was a drug addict, and the father was in jail, but the uncle just flat-out loved the kid.”

Livingston said that caring adult can be a teacher, social worker, Scout leader, neighbor, you name it.

“A caring adult for me was a Miss Bigge,” he said. “I was a psychology major. I had no interest in education. Then, I took this psychology-of-the-exceptional-child class. The content of the course opened the door, because she was so passionate about it.”

Every child can learn

At the community colleges, Livingston met a lot of 27-year-olds who had dropped out of high school because of “bad homes, bad attitudes, drugs, alcohol or they got pregnant,” he said.

Getting to know these students convinced Livingston that young people don’t drop out in high school. They actually “drop out” in the fourth grade.

Livingston explained: “They come to kindergarten ill-prepared. A kindergartner who has never held a pencil, never used crayons, never held a book, (competing) in the same classroom with kids who have used computers.”

From kindergarten through third grade, teachers focus on the process of learning information, he said. By fourth grade, they delve into content.

“If you can’t process information, you’re not even in the game,” he said. “We create, because of that frustration, a lot of bright kids who become behavioral problems. Mentally, they drop out in fourth grade and quit coming at 16.”

Creative and tenacious teachers can reach those frustrated children and unlock their ability to learn, Livingston believes.

One year, Livingston – who served as superintendent of Spokane Public Schools from 1993 to 2001 – met a fourth-grader at Regal Elementary School.

“I was in the library and this kid was doing a PowerPoint on presidents. He was merging databases,” Livingston said.

“It was very early in PowerPoint technology. I watched him, amazed. His teacher said, ‘When he first came here, he was a real behavior problem. Then he got into technology.’ ”

Every child needs high expectations

“We mislead children when we tell them their self-concept comes from within. It doesn’t,” Robinson said. “We give our children their self-concepts. When we communicate our expectations and impressions, they etch in how they understand themselves. That’s why self-fulfilling prophecies are so powerful.”

Robinson has one caveat about expectations.

“We shouldn’t tell children they can do anything if they just try hard enough,” he said. “You need to find out where you are gifted and then invest in your strengths.”

Every child needs a safe place

What characterizes a safe place? Livingston’s definition: “They have caring adults there. Kids want to be there. It’s clean.”

He applauds the clean, safe places where children in poverty find adequate food – an essential component for healthy growth.

“One summer I was at Bemiss (Elementary School) in the morning, and then in the afternoon I was at Garry Middle School, and this kid was sitting there. I said, ‘Didn’t I just see you at Bemiss for breakfast?’ He said, ‘This is where I eat.’ He figured out how to get breakfast and lunch. We were providing something very important.”

Every child should be asked, ‘How can I support you?’

Robinson said: “One of the things we can do for children is not only tell them what they need to prepare for prosperous adulthood, but ask them how we can support them.”

When his children were little, Robinson asked how he could support them in reaching specific goals. For instance, if a child wanted a later bedtime, he’d ask: “What kind of grades do you think you have to get to stay up until 9?”

Now that his children are adults, he asks more general questions, such as “What are the kinds of things I can do to help you grow in your career?”

Every child needs to know it’s OK to admit mistakes

Both men admit to regrets and mistakes, and attest to the importance of facing both in life.

“I always tried to put Nick’s soccer games on the calendar,” Livingston says of his only child, now grown. “But obviously there were things we could have/would have wished we’d done. When they are gone, they are gone.”

Robinson said: “I made so many mistakes. What has helped me deal with regrets is to enter into this tension: All of us are so very broken and so very blessed. It’s important for me to never forget my brokenness or forget my giftedness. If I can live in that tension, at least I have something to do with the regrets.”