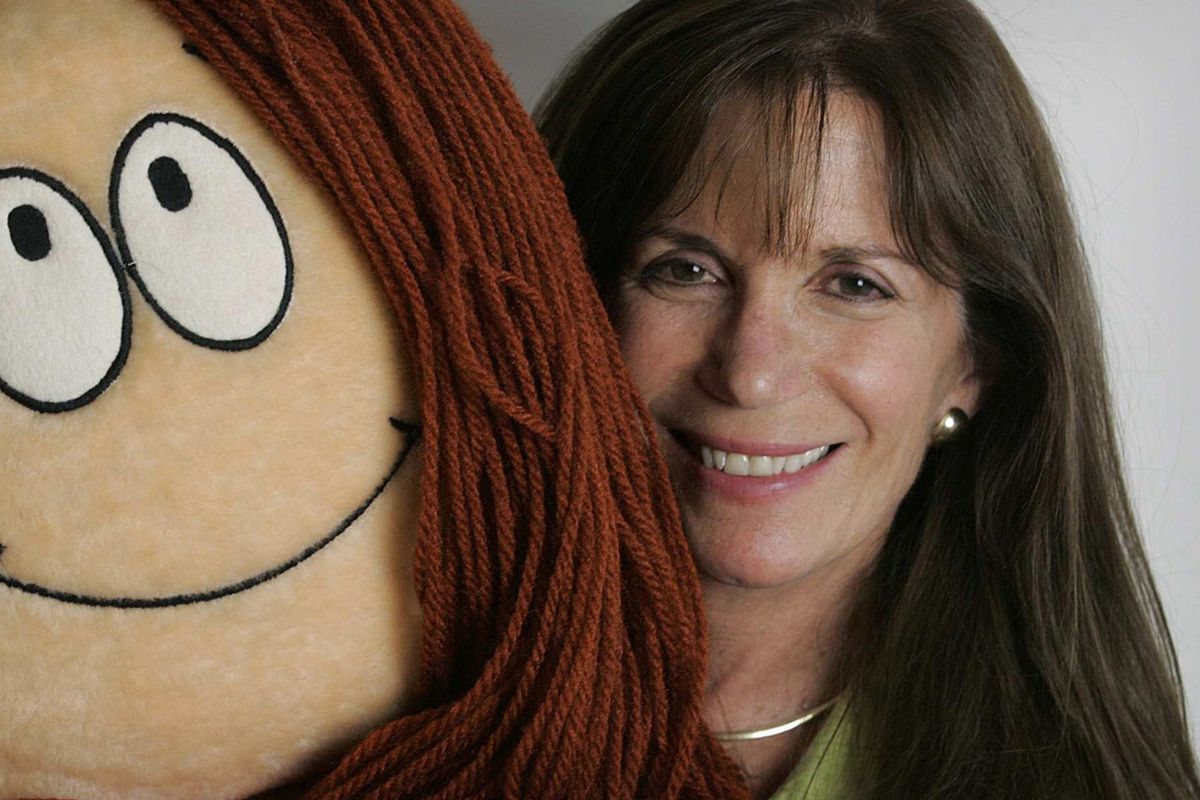

Author of famed ‘Cathy’ comic strip ready for new challenge

Cathy Guisewite doesn’t know what the last four panels of her “Cathy” comic strip will look like when they run in 700 daily and Sunday U.S newspapers in early October.

In fact, even after a nearly nonstop, 34-year run of putting words in the mouth and anxieties in the mind of her alter ego, she’s hard-pressed during an interview to say what the next four panels will look like – even though a deadline looms in less than 24 hours.

“Quick, give me ideas!” Guisewite says as she sits behind the desk of her Studio City, Calif., home office.

At first glance, the desk, with its gleaming white iMac in one corner and a disappointingly small stack of folded newspapers, Vogue magazines and scribbled-on scraps of paper (“I just did a huge cleaning”) in another, seems incongruous with the widely beloved (and more than occasionally skewered) paper-piling, dressing-room loathing Everywoman comic strip character that has evolved in this room for the last 17 years.

Then one notices the word “AACK,” Cathy’s familiar utterance of exasperation, rendered in large wooden letters on one of the four white walls, and the four rectangular windows above the Porta-Trace light box on which she draws.

Guisewite literally frames her view of the world in four panels – just like a daily cartoon strip.

And now she wants out.

Last week, when she announced that the last of the daily “Cathy” strips would run Oct. 2, with the final Sunday strip appearing the following day, Guisewite said she wanted to quit to spend more time with her family.

Ensconced in the bubble of her quasi-comic-strip office, surrounded by ceramic Cathy cookie jars, stained-glass Cathy wall hangings and shelves full of Cathy figurines, she explains that the constant deadline pressure of generating a daily strip has made it hard to do much else.

But is Cathy done?

“I’m open to any and all possibilities,” Guisewite says. “All I can’t do anymore is the daily deadline, because right now I’m so obsessive about the way I create the comic strip it doesn’t leave me any time to do anything else.”

By her own reckoning, Guisewite has done more than 12,000 strips, with the only extended break coming when she took eight weeks of maternity leave to spend with her newly adopted daughter in 1992.

“In the last several years I’ve had one month off out of the year,” she says. “Which I use to do things like clean out the trunk of my car.”

The comic strip debuted in 1976. Guisewite was living in Detroit and had freshly embarked on a career in advertising.

She started sending her parents stick-figure communiques that lamented her relationship travails, workplace frustrations and diet-based angst. At her mother’s urging, she sent a packet of material to Universal Press Syndicate – and the company sent back a contract.

“They said they loved the emotional honesty of my submission and that they were confident I’d learn how to draw if I had to do it 365 days a year,” Guisewite says, noting that she considers herself a writer first and foremost.

Even her critics understand her place in pop culture.

“I have to be honest, right up front, I’m not a big fan of the artwork,” says comics historian Charles Solomon.

“But when she started, there were far fewer women cartoonists. And this wasn’t just that she was a woman cartoonist, but the strip spoke to the daily life of women, and there hadn’t been anything like that before.

“I think that’s what helped it overcome its visual limitations – the idea of a woman speaking to other women, trying to find romance. That was something new.”

Chronicling the foibles of a serial-dieting, mom-guilted, relationship-challenged, relapsing shopaholic tapped into the reservoir of feelings shared by many women.

Over the years Cathy has appeared in three animated TV specials (one of which won Guisewite an Emmy), countless books and a slew of licensed products that have included Cathy cake pans, chopsticks, greeting cards, life-size stuffed dolls, ceramic cookie jars, figurines and candy boxes.

The strip once appeared in 1,400 newspapers (including The Spokesman-Review, which hasn’t published it for several years).

Guisewite’s desire to be honest and truthful to the female of the species resulted in a move that fundamentally altered the direction of the comic strip forever – a change that longtime “Cathy” fans simply refer to as “marrying Irving.”

After years of dating drama, the main character married her boyfriend in a February 2005 strip.

“That I am guilt-stricken about,” Guisewite says. “Because I had promised that Cathy would be the single woman that would not abandon the other single women by getting married. That’s every single woman’s experience: that one by one all of her friends jump ship.”

But Guisewite (who married screenwriter Christopher Wilkinson in 1997, and since separated from him) says she was committed to making the strip “as much as I could from the heart.

“And by that time I’d been married (for several years) and I couldn’t write about dating, about being single anymore. The world of being single had changed radically. So that was my conflict.”

And a source of tension.

“That’s the thing about comic strips and their creators,” says Ben Schwartz, author and comics historian. “They don’t age the same way. It’s hard for creative people to keep going back to what’s best about the strips and to keep growing creatively at the same time.”

It’s a tension that Guisewite, who celebrates her 60th birthday next month, acknowledges.

“I was somewhat obligated to keep Cathy’s age as vague as possible so women of a lot of different ages could relate, so I couldn’t really write about being my age,” she says. “That’s not appropriate for her.”

As for what she has next, “cleaning out the trunk of the car is the only thing I have for sure,” Guisewite says.

Then she adds, “I think I’m doomed to be a writer.” She has folders upon folders labeled “fashion,” “diet” and “relationships” crammed with magazine pages, orphaned jokes and half ideas.

“I’d be thrilled,” she says, “to write something where I didn’t have to stop and draw it every four or five sentences.”