Book aims to connect new generation to grandmothers’ skills

Sandy Colquhoun, 61, says growing up she didn’t necessarily see eye-to-eye with her mother, Jean Dinsmore, 91, when it came to housework. (Dan Pelle)

Erin Bried is hoping to teach a generation of women the skills their grandmothers took for granted, such as how to shine your shoes, swaddle a newborn and spring-clean your home.

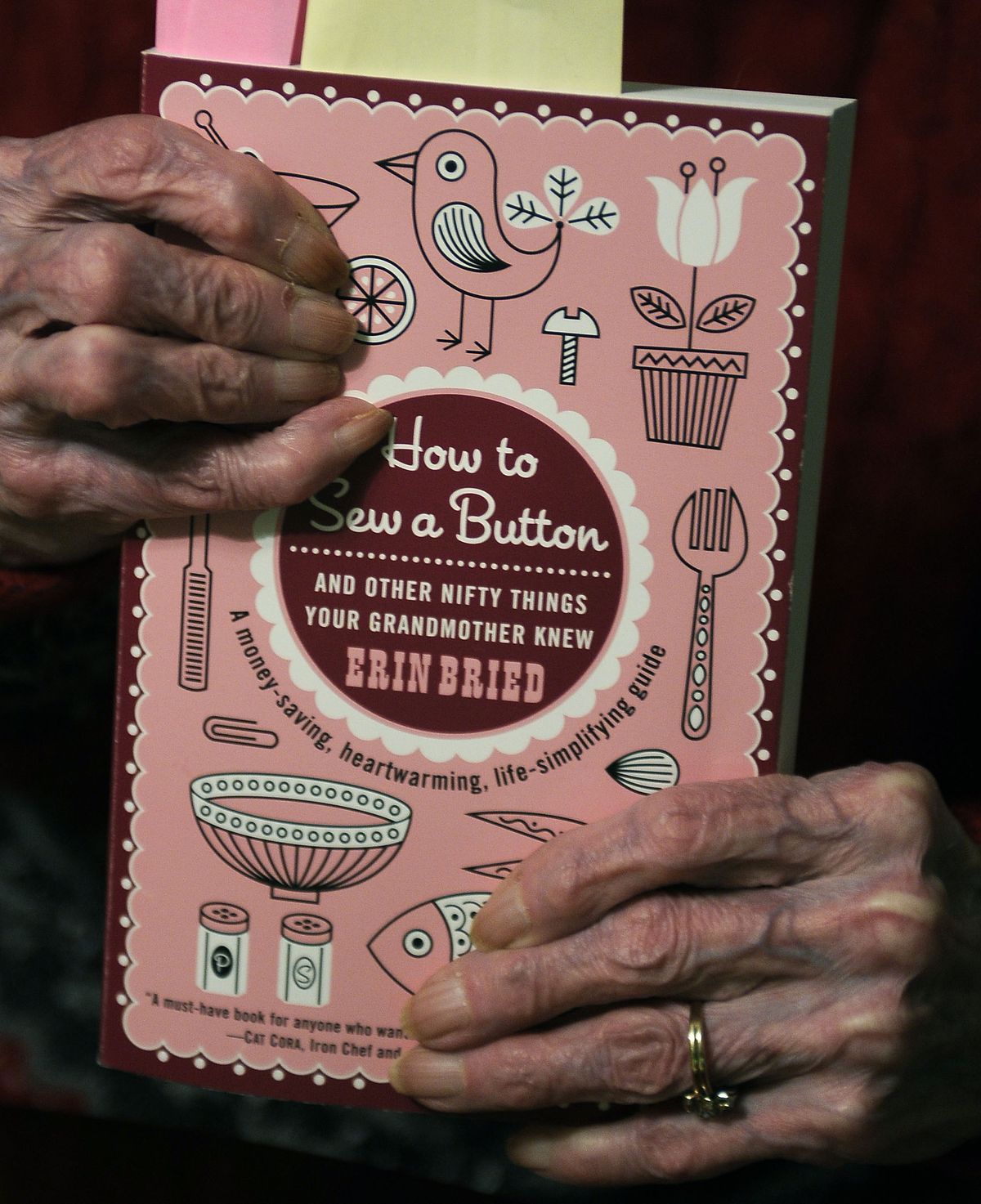

And sew on a button, of course, because the title of Bried’s new book is “How to Sew a Button – and Other Nifty Things Your Grandmother Knew” (Ballantine, 304 pages, $15).

“I’m 35, and I hadn’t roasted a chicken before I wrote this book,” Bried said in a recent interview from her Brooklyn, N.Y. home. “I make it once every two weeks now. It’s delicious.”

Bried interviewed 10 grandmothers throughout the United States who grew up during the Great Depression, including Jean Dinsmore, 91, who lives in a retirement community in North Spokane.

Bried’s book is one more indication of an intriguing generational phenomenon. The “home production” skills that Depression-era women learned from their mothers – and carried with them into their own homes in the 1950s – were sometimes rejected by their liberation-era daughters.

Now, the grandchildren of these grandmas hunger for those lost skills, such as baking from scratch and knitting.

How to Mop. Step 1: Send everyone with pitter-pattering feet packing, move any furniture that’s in your way, and put on some good music. Remember, the word mop doesn’t end with an “e.” Step 2: Sweep the floor. Step 3: Fill a bucket with cold water and add a squirt of dishwashing detergent. Step 4: Dunk your mop, thoroughly wring it out, and go to it.

– From “How to Sew a Button”

Jean Dinsmore grew up on a farm in Troy, Idaho, one of four children.

“Because her local hospital shut down due to the 1918 flu epidemic, Dinsmore was born at home. … She still has the old kerosene lamp that was burning the night she was born,” Bried writes in her book.

“We used to trap squirrels, my sister and I,” Dinsmore recollected in a recent interview. “My dad gave us 2 cents for every squirrel.”

From her mother, she learned how to cook, clean, do laundry, sew and knit. She tried to bake pies, but her mother was a pie crust perfectionist, and so Dinsmore never perfected them, but she made some mean cinnamon rolls.

Dinsmore grew up around women who dedicated yeoman’s hours to chores. A 1920 Ladies Home Journal article calculated that meal preparation took up nearly 30 hours a week and washing dishes consumed another 10. Sewing and mending took nearly four hours out of the typical week.

“My mother made our clothes,” Dinsmore told Bried. “She’d buy the material, but some people used flour sacks.”

Dinsmore graduated from the University of Idaho in 1939 and worked as a teacher for a year before marrying and having her two children.

Time spent on traditional women’s work didn’t decrease for the housewives and mothers of her generation, despite modern appliances which proliferated in the 1950s and 1960s. Full-time housewives sometimes spent as much time on housework in 1965 as they did in the 1920s, according to a National Bureau of Economic Research report.

French writer and early feminist Simone de Beauvoir was one of the first to complain. In the late 1940s, she said: “Few tasks are more like the torture of Sisyphus than housework, with its endless repetition: the clean becomes soiled, the soiled is made clean, over and over, day after day.”

How to scent your home without candles. Step 1: Put that $30 you were about to spend on a fancy candle back in your pocket. Step 2: Pour water into a small pot and place it on the stove over low heat. Step 3: Add several cinnamon sticks, and if you’d like, cloves and peels of a lemon, orange or apple. Step 4: Let simmer for as long as you’d like, making sure there’s always water in the pan.

Sandy Colquhoun, Dinsmore’s daughter, is 61. Though she majored in home economics at the University of Idaho, she remembers well the rebellion of her generation of women against most things traditional, especially the work of the home.

“We were purposely saying that it’s passé,” she says. “And who cares if it’s not clean? There are more things in life than having your house be clean. We didn’t want things that looked homemade. It was time-consuming. It was easier to buy things. ”

Colquhoun, a librarian at Post Falls Middle School, is grateful now that she learned some traditional skills from her mother, such as sewing and baking, including the making of those mean cinnamon rolls.

In the 1970s and 1980s – the height of the women’s liberation movement – time spent on housework began to decrease. By 1995, women spent an average of 15 hours a week doing housework, compared with 26 hours in 1965.

Men picked up some of the slack, according to the book “Time for Life.” By 1995, they were doing nearly 10 hours a week of housework, double the amount they did in 1965.

Rebellion by daughters against the work of their mothers fits another generational reality. The pendulum swings back and forth between the generations.

“A lot of these skills skipped a generation,” Bried points out.

How to remove grease, red wine or coffee (stains). Step 1: Mix ¼ cup white vinegar with ¼ cup cold water. Stir in 1 teaspoon laundry detergent. Step 2: Apply the solution to the stain and dab with a paper towel. Step 3: Rinse with cold water.

Bried’s book contains more than 100 life skills. Not all of them involve housework, sewing or cooking.

She includes a tip on how to brew your own beer, for instance, and brewed some for her book party.

Her book “has a pink cover, but it can be useful to men and women,” Bried says.

She likes to quote another grandmother who said, “There was no men’s work or women’s work. There was only work, and anybody who was around was expected to chip in.”

And speaking of housework, no one’s doing a Depression-era share of it anymore. On an average day, according to the 2008 American Time Use Summary report, 83 percent of women and 64 percent of men spent some time doing household activities, such as housework and cooking. The category also included lawn care, plus financial and other household management tasks.

Women spent an average of just 2.6 hours on these activities, while men spent two hours.

Bried’s hoping that the book inspires people to try some of the old tips, and also interview the grandmas surrounding them.

“The biggest lesson I learned writing the book? Being rich has nothing to do with your bank account, and it has everything to do with your resourcefulness and your generosity of spirit and your ability to find joy in good times and bad times,” she says.

“Our grandmothers knew it, and we should all keep it in mind.”