Backpackers vie for shot at gnarly route on Vancouver Island

Serious backpackers nod knowingly when you mention the West Coast Trail.

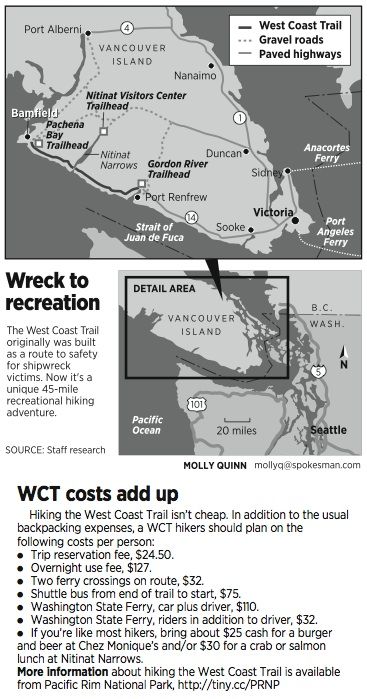

Either they’ve done the rugged 45-mile hike along the southwest coast of Vancouver Island, or it’s on their must-do list.

Canada’s Pacific Rim National Park offers only 60 permits a day for starting the trail during the May-September hiking season. Demand is high for those coveted permits even though the trail is infamous for challenging hikers to a boot-camp experience of:

• Climbing and descending ladders in various stages of repair to negotiate gorges,

• Waiting for low tide to venture out on sections of coastal shelf booby-trapped with surge channels and seaweed-slickened rocks,

• Enduring days of rain or fog,

• Slogging through sections of rain-forest mud that would make a pig squeal.

I was one of hundreds, maybe thousands of hikers hunched over my computer at 1 a.m. on June 1 when the permits for August became available on the park’s website.

Within minutes, most of the permits for the month were snapped up by adventurers from around the world.

Word has been out for a long time that hiking the WCT is a grueling way to have the time of your life.

The route was hacked out of forest and otherwise impenetrable bogs in the late 1800s for a telegraph line. The trail was enhanced starting in the early 1900s to provide a land route to safety for survivors of numerous shipwrecks that were occurring as Pacific Ocean vessels entered the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

The trail has been vastly improved for recreational hiking in recent years with two small ferries across inlets, 108 bridges, 38 ladders or multi-ladder structures, and five hand-pull cable cars for crossing flood-prone rivers.

Yet the route is distinguished from virtually any other national park trails by the casualties: An average of 88 WCT hikers a season have required emergency boat or helicopter evacuations in the past decade.

“Most of the injuries result from slip, trips and falls,” said the park staffer who presented the mandatory orientation for hikers starting from the south at Port Renfrew. “Don’t be in a hurry.”

Our group of three took the warning seriously. On the first section of trail, with our packs at their heaviest, we stepped carefully through an endless tangle of tree roots and rocks averaging about 1 kilometer an hour.

We were humbled halfway through the day by a runner racing toward us wearing a daypack and holding a water bottle in each hand. He barely nodded to us as he strained to concentrate on his footing.

Later we learned that he was in the process of setting a WCT speed record of 10 hours, 8 minutes.

My wife, Meredith Heick, and our friend, Romany Redman, were hiking the route in six days.

Most hikers plan for seven days, which, in retrospect, is the best option for making sure you can explore all the trail offers.

For example, hikers starting from the south must wait for an 8:30 a.m. ferry across Gordon River to reach the trailhead. Without the flexibility for an early start, we missed the low tide and the option to hike on the coast around Owen Point and see some of the trail’s most scenic sea caves.

With an extra day on the trail, we could have hiked an easier day to camp at Thrasher Cove and hit prime tides the next day. Instead, we had no choice but to stay on the inland route to Camper Bay, with little time to look back.

The rigors of the trail faded at camp that first night as we began mingling at driftwood fires and meeting groups of hikers who were roughly on our same schedule.

In the next few days, their trail personalities emerged. Among them were:

The strollers, who through various combinations of curiosity and photography or misery and fatigue where always late arrivals at group camping areas.

The barn horses, who put their heads down and made a beeline to the next campsite, rarely stopping to explore beaches, sea lion congregations, tide pools, waterfalls, lighthouses or other attractions along the way.

The isolationists, who preferred secluded campsites.

The pyros, who became magnets of social discourse by immediately gracing their campsite with a beach fire regardless of the weather or abundance of daylight.

The speedsters, who left the first camp early never to be seen again.

The dropouts , who bailed out after a full day of rain midway through the trek at Nitinat Narrows, where boat access offers the only easy way out for hikers who have a change of heart. The First Nations ferry operators, who also served fresh-caught salmon and crab on the dock to hungry hikers, said they’d seen as many as 40 hikers abandon their trips in a single day during bouts of bad weather.

The WCT hikers and their stories were as stimulating as hiking the trail.

A college girl had brought her roommate on the WCT for her friend’s first backpacking experience and exposure to instant oatmeal and Clif bars. Wisely, they brought along enough moleskin to carpet a small apartment.

A couple who had hiked the WCT during their honeymoon 20 years ago were back with their two young boys.

A Dutch couple shared their encyclopedic resource of walking vacations all over the world.

A musician crooned on his harmonica to gently wake camp stragglers who needed to get up and beat the high tide.

Olga, the Russian immigrant, captivated us with her hard-luck life story and survivor instincts on a dreary morning under the tarp we’d strung up to shed the drizzle

A couple with their two teenage kids had scrimped on vital clothing after spending so much money on family equipment plus the WCT fees totaling well over $1,000. We watched them suffer in their cotton socks and plastic rain gear that ripped and flapped in the wind within the first few hours out of their packs.

But they endured, and even flourished.

We met several mom-and-son teams, including one young man who proudly praised his mother’s trail cooking skills as she prepared fresh naan on her single-burner stove.

“This trip is like a progressive dinner,” he said.

The best campfire discussions included a Canadian with 30 years of foreign service and an Iranian who escaped in political exile only to be imprisoned in Turkey for a month before a Canadian consulate secured his release.

One night, U.S. involvement in the Middle East became a hot topic that stoked and smoldered like the coals in the beach fire that brought us all together.

“Tomorrow we continue where we left off,” the Iranian shouted, smiling and raising an arm as the fire dimmed. We agreed, as we dispersed to zipper into our tents, engulfed in darkness and the constant sound of the pounding surf.

Perhaps most impressive was Rick, a school principal from Winnipeg, who was hiking with his daughter, Becky, and her husband, Josh.

We met them at the pre-hike Park Service orientation, where the park staffer warned, “The West Coast Trail is either a bad place to come if you’re afraid of heights, or a good place to get over it.”

Since there was no way to hide his affliction on a trail littered with log bridges, ladders and cable crossings, he told us right off that he suffered from acrophobia.

“I can’t reason with it or talk myself out of it,” he said. “I’m terrified of these ladders.”

At each bout with height – and there are many – Becky would assist her dad with her soothing grade-school-teacher demeanor while Josh would follow, making two trips up and down every ladder to carry the pack for his father-in-law.

We watched Rick squeeze the blood out of his fingers as he gripped the cable car railings. He fought away the demons on a suspension bridge and inched down each ladder with his arms wrapped around the wood beams as though he were holding on against hurricane-force winds.

His one weakness gave us all strength.

“It would be a shame to let my problem keep me from doing a trip like this with my daughter,” he said.