Longtime falconer trains teen ‘bird nut’

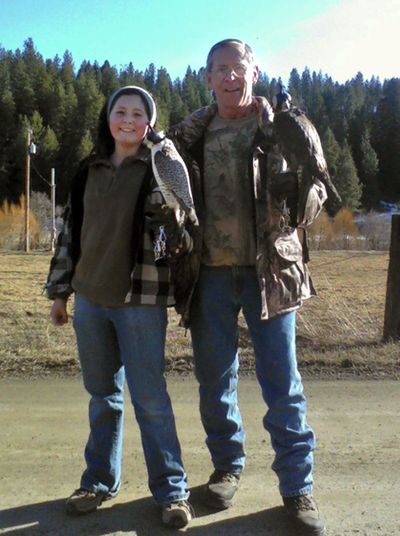

Hunting with a bird instead of a gun may sound peculiar to some, but not to master falconer Gary Starr, of the West Plains, and his 14-year-old student Melissa “Missy” Snow.

In falconry, a person trains a raptor to pursue wild game. This 40-year passion for Starr began at age 10 when he eagerly watched a hawk flying with prey to feed its babies. He asked his parents about falconry as a boy, and recalls, “They replied, ‘absolutely not.’ ”

He managed to get his first hawk as a sophomore in college. Now, his grown children and grandchildren know falconry – as does his determined pupil.

A self-proclaimed “bird nut,” Snow began studying more than a year ago after being captivated by one of Starr’s falconry presentations.

“Mr. Starr said I got infected with the ‘bird disease,’ ” she said jokingly.

Falconry may evoke images of a medieval man with a gauntleted arm carrying a hooded bird, but not a teenage girl in the technology age. Snow recently took a 164-question federal falconry examination so she can have her own raptor and become an apprentice. She described a training exercise, a sense of awe clear in her voice: “He flies them really high up to a kite with a lure on it. The bird will go up, grab the lure and bring it all the way down. Amazing.”

Of the estimated 4,000 falconers in the U.S., there are roughly 480 women and 25 teenagers, according to Donna Vorce with the North American Falconers Association.

The small numbers are no wonder – it takes a lot of time to train, care for and hunt with a raptor. Before that, there’s an exam, equipment and facilities to procure. “They are very, very far from pets,” Starr emphasizes.

There are two basic kinds of falconry, he said: short-wing and long-wing. A short-wing falconer flies a hawk for ground prey, such as cottontail rabbits. Long-wingers fly falcons.

“Gyrfalcons are the fastest-flying, straight and level bird on earth and can catch pretty much anything they want,” he asserts.

During a hunt, Starr unhoods the bird so it will fly to its maximum pitch, flush out the prey and attack. There are risks in recovering a falcon with its prey, so he defines a good hunt as one “when you get your bird back.” He once chased a falcon for 20 miles down Highway 2 using telemetry technology to locate it.

Starr said he makes friends with landowners and asks, “Can I come hunt on your land? I don’t use a gun.” It puzzles them, but they usually agree and want to watch. These are hands-on experiences that an apprentice must learn.

Starr, a full-time falconer and raptor breeder, hired Snow to help with the birds.

“I’m saving up to build my ‘hawk house,’ ” she said.

He plans for her to help train the new babies.

“She will learn the process of getting the bird to reach a tolerance level for sitting on the gloved fist,” he said, adding, “she’s going to be terrific. When I look at her I see myself when I was 10 years old.”

Starr studied ornithology in graduate school. Governments and airports use falconry, as does research in bird abatement, which involves the chasing away of nuisance birds in farming and environmental applications, Starr said.

Snow’s life became bird-focused when her family moved to the country.

“I started noticing all the birds and liking them,” she said. She gave subtle cues for chickadees to land on her head, then hummingbirds on her finger. She rescued various birds, raised button quail and now is manning falcons.

“My parents are supportive,” she said, “as long as I pay for it myself.”