Washington not ready to handle Alzheimer’s increase

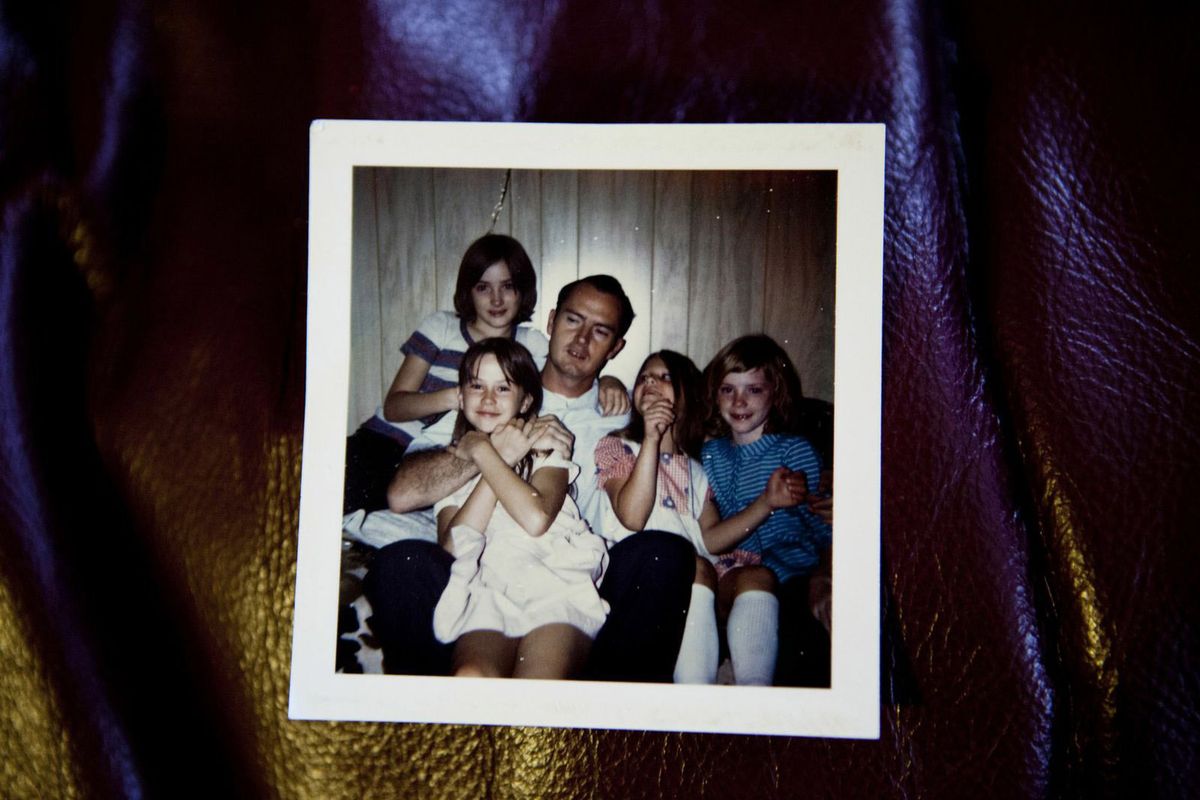

In this family snapshot from the 1970s, Sam Counts is seen with, from left, his daughter Sue, niece Vicki Counts, niece Jill Counts and daughter Samantha Counts. Sam Counts went missing last November and was later found dead on a logging road.

In the first decade of this century, the number of elderly Washington residents living with Alzheimer’s disease increased by one-third. That number is expected to balloon by a third again by 2025. Crucially, six in every 10 of those stricken by Alzheimer’s, and many with other forms of dementia, will wander or get lost, placing themselves and sometimes others at risk, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Wandering behavior has become increasingly familiar. Yet Washington is not prepared to deal with this emerging public health threat:

• Few police departments have policies or training to educate officers about Alzheimer’s or dementia.

• An Amber Alert-like system set up in 2009 to help find wandering people is underused, its coordinator acknowledges.

• Bills to create a formal Silver Alert system like those in more than 20 other states foundered in both houses of the state Legislature this year.

• Washington is also one of just six states that haven’t even started work on a statewide Alzheimer’s plan, even as the population at risk of wandering surges.

“This is really ironic when you consider Washington’s historical willingness to be out in front,” said Bob Le Roy, president and chief executive officer for the Western and Central Washington chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association.

Le Roy’s group began to lay the groundwork for a statewide Alzheimer’s plan five or six years ago, but it stalled during a freeze on new programs during the economic downturn.

Over the last 16 months, at least seven people from Washington have died as a direct result of wandering, according to an analysis of media reports by InvestigateWest and interviews with law enforcement officials. The exact number is unknown; no public record is routinely created when wandering is a contributing factor to death, and no state agency keeps such a tally.

Sam Counts, a 71-year-old Spokane Valley man with early-stage dementia, is a telling example. After a day of Christmas shopping last November, he drove to the store for bread. His body was found a week later on a logging road near Mount Spokane State Park – and then only after the Spokane County Sheriff’s Office put a search helicopter in the air. His pants were caked with mud and a flashlight was found nearby, according to the autopsy report.

“He’d been to the bread store a million times,” his wife, Donna Counts, told InvestigateWest in a recent interview. She took a deep breath. “I shouldn’t have let him go.”

Similar stories across the state suggest the problem is more common than many public safety officials realize. Over the last five years, there have been at least 33 media reports in Washington of people with dementia who were found safe. King County Search and Rescue has responded to 10 cases involving Alzheimer’s or dementia since the start of 2012, all of which ended safely. Countless other cases are not reported to the police, not reported in the media or both, according to experts.

There is no mandatory waiting period to report endangered adults as missing. That can happen in the first hour that someone with dementia is missing, authorities say.

Police need Alzheimer’s policies

In Steve Wright’s long policing career, he has seen most every kind of search and rescue mission. And he has seen Alzheimer’s up close. His mother-in-law had the disease, and he, his wife and his daughter all became caregivers.

“It’s a hard, hard row to hoe,” he said.

In May, Wright stood before about four dozen police officers and other first responders at the Oregon Public Safety Academy in Salem to share enough information about Alzheimer’s that when those in the room encounter it on the job they can react appropriately. It was the first such training in the Northwest organized under the auspices of the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

Wright shared stories of his own mother-in-law, who remembered living with her husband at a military base in Alaska even as she would forget to eat. Soon Wright ventured into wandering: “Sixty percent of Alzheimer’s patients who wander, if not found within 24 hours, are going to die. Eighty percent, if not found within 72 hours, are going to die.

“I don’t know how to say it any plainer than that,” he said.

On foot, wanderers tend to stay in the community, and most are found near where they were last seen. Seventy-five percent are found within 1.2 miles in flat, temperate areas such as Eastern Washington, and half are found within a half-mile, according to Robert Koester, author of “Lost Person Behavior,” a search-and-rescue manual. When a vehicle is involved, the search radius immediately grows, but even then, there are clues where to look.

“Often they’re going to where they used to live, or perhaps where they used to work,” said Chris Long, the state’s search and rescue coordinator. “They have some destination in mind.”

Remarkably, just half a decade ago little of this was known outside of search and rescue circles. The police chiefs’ Alzheimer’s Initiatives program, which organized the recent training in Salem, launched with funding from the U.S. Department of Justice in 2009 to help police and other first responders learn how to protect and serve people with Alzheimer’s, including those who wander.

“The training and preparedness of law enforcement agencies is all over the map,” said Amanda Burstein, the group’s project manager.

The police chiefs’ most urgent recommendation is a written policy on Alzheimer’s and dementia for every police department.

“There are characteristics of a wanderer when dementia is in play,” Burstein said, versus a typical missing persons incident.

In interviews with police departments and sheriff’s offices in Washington where wanderers have died or gone missing, InvestigateWest found just a handful are aware of this distinction, and only one – the Anacortes Police Department – reported having formal training on wandering behavior.

At the training center in Salem, only one hand in 40 went up when Wright asked which departments already had a policy specific to dementia.

Wright repeated the call for a written policy: “I encourage you to invoke one of these because there’s a high likelihood if someone’s found 100 yards away after searching the whole county, it kind of makes your organization look a little goofy.”

The training gap, possible solutions

Washington is a national leader in search and rescue. In recent years, however, government belt-tightening has hindered efforts to better prepare and equip local law enforcement to handle missing person cases involving dementia, according to interviews by InvestigateWest.

The system appears to have broken down in the face of limited training opportunities for local law enforcement to learn about dementia and, at times, reluctance at the local level to use the tools available to law enforcement agencies. Outside of law enforcement, few systems are in place to help families and communities learn about, prepare for and respond to the growing number of individuals with Alzheimer’s and dementia who are prone to wander.

Bill Gillespie is president of the state’s Search and Rescue Volunteer Advisory Council, which oversees an annual conference and tracks search-and-rescue missions across Washington.

The types of searches are changing, he says. “We are seeing a significant number of what we call ‘walkaways.’ ”

Even so, Gillespie guesses that as many as a third of all wandering cases that get reported never cross his desk. Local police are sometimes reluctant to call for search-and-rescue volunteers and incur the related costs of doing so, when so many cases are wrapped up quickly, he and other experts say.

He’d prefer to hear about every one. “We’ve made it very clear to law enforcement,” Gillespie said.

In 2009, the state gave local law enforcement a potentially helpful tool, but it’s been underused. The Endangered Missing Person Advisory, an analog to the better-known Amber Alert system for missing children, is designed to alert the public when an at-risk individual goes missing, a classification that includes not only Alzheimer’s and dementia but also mental illness. When one of these emergency notifications is activated, law enforcement agencies in the state are notified, along with ports of entry, news media and members of the public who subscribe to the notices.

Only in the last 12 months have law enforcement officers been able to issue EMPA advisories through a Web portal, and no advisories were issued through the portal in 2012, according to Carri Gordon, Washington’s EMPA coordinator. One reason: No one had yet received training on how to do so.

Even this year, “It’s been used not as often as it should be,” Gordon acknowledged.

Two bills to create a companion to EMPA called Silver Alert failed to make it out of committee. Since 2006, more than 20 states have enacted Silver Alert legislation, most recently New Mexico and California, where the program contributed to the safe return of an elderly California man less than 48 hours after it went into effect.

With or without such legislation, experts say, police agencies more and more are working on the front line of public health when it comes to wandering behavior.

“Not only do they have to have the expertise to conduct proper searches,” said Wright, who provided the training in Salem, “they need a proper knowledge about the disease and what’s going to occur.”

“That trend is not going to change,” he said.