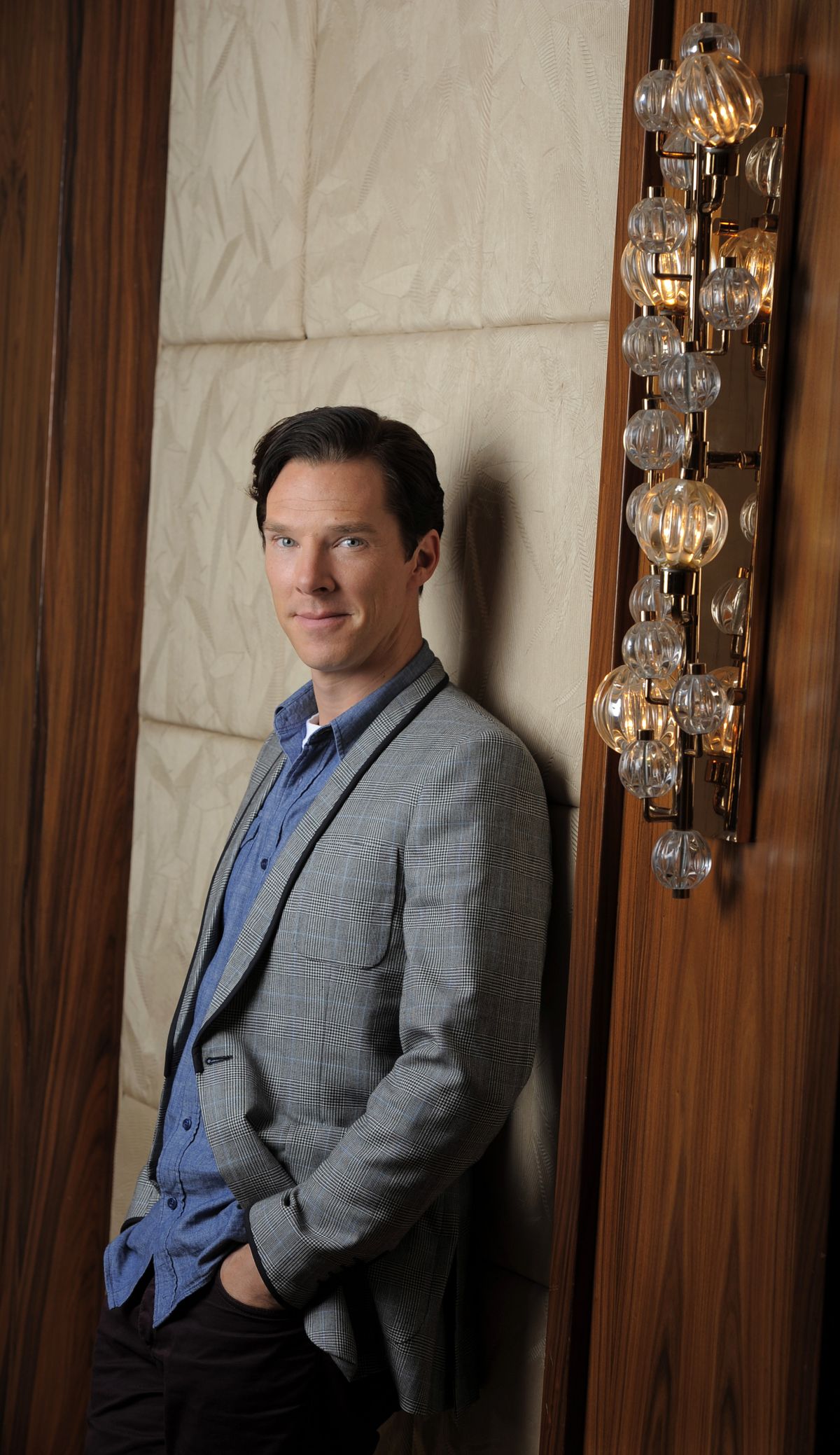

Cumberbatch drawn to WikiLeaks founder’s ‘precarious’ life story

TORONTO – Over the past year, between work on the multitude of films and TV series Benedict Cumberbatch seems to be involved in (“12 Years a Slave,” “August: Osage County,” “The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug,” “Sherlock”), the British actor would find himself, now and then, walking along Hans Crescent in the Knightsbridge section of London. He would pass the Embassy of Ecuador, not far from the fabled Harrods department store, and think about dropping in.

Why not? He had a few thoughts he could share with Julian Assange, the WikiLeaks founder who has been holed up inside the embassy – and whom Cumberbatch portrays in “The Fifth Estate.”

“Sadly, I did not go in,” says the actor while at the Toronto International Film Festival. “I would have liked to meet him. I don’t know whether he’d want to, though. And if it did happen, I hope it would be a very private event between two men who have been very oddly drawn together in this strange way.”

When “The Fifth Estate” project was announced – adapted from the books “Inside WikiLeaks: My Time with Julian Assange and the World’s Most Dangerous Website” by Daniel Domscheit-Berg and “WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy” by British journalists David Leigh and Luke Harding – Assange contacted Cumberbatch and pleaded for him to beg off. Neither book portrays Assange in the most flattering light, and the Australian-born hacker-turned-journo- trailblazer was not thrilled.

“It’s no secret that we’ve communicated,” Cumberbatch says. “We exchanged emails at the beginning of the job. Not many. Basically him saying, ‘Please don’t do this film,’ and me saying, ‘This is why I feel it’s actually not a bad thing, and I do want to do this film.’ And that’s where that was left.

“I have a real care for him and his real-life situation, because it is very precarious. But this is a film, it’s not a documentary, it’s not a piece of legal evidence. It’s a dramatization of a certain account of events. There’s a lot of caveats there.”

Directed by Bill Condon, “The Fifth Estate” – opening in theaters Friday – is a whirligig of a movie that traces Assange’s rise from Down Under upstart to whistle-blowing guru to an international hot potato caught in a sex scandal, and sought by several governments, including the United States.

Along the way, Assange seems to transform from idealist crusader to somewhat meglomaniacal and paranoid figure. Daniel Brühl, who plays Formula One racing legend Nicki Lauda in “Rush,” is Assange’s early ally-turned-disillusioned ex-WikiLeaks associate Domscheit-Berg.

If you’ve seen Assange on YouTube, or in Alex Gibney’s “We Steal Secrets” documentary, and then you watch Cumberbatch in “The Fifth Estate,” the mannerisms, gait, rhythms of his speech, look in his eyes, even his dance moves (Assange is a terrible dancer) are dead-on.

“There’s an intelligence, a charisma, which you can’t fake, and Assange has that, and Benedict has that, too,” says Condon, the director of “Gods and Monsters,” “Kinsey” and “The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn.”

“It’s a lot of work. That just doesn’t happen easily,” the director notes in a separate interview. “It’s not dissimilar to what I went through with Ian McKellen in ‘Gods and Monsters’ and Liam Neeson in ‘Kinsey’ – British actors who start on the outside and then move in. The first thing is the wig, and the teeth for Benedict, and the frock, and the voice, obviously, and then they go deeper and deeper and deeper.”

Condon was also struck by the way his star handled the email entreaties from Assange.

“Just imagine you’ve got an actor who is that serious and who is already in the process, in rehearsals, and you’re about to start shooting – his job, which he takes very seriously, is to channel Assange, is to become Assange. He’s not Daniel Day-Lewis, but he did become that person,” Condon says.

“So imagine you’re doing that, and then you open up your computer, and the person you’re channeling – your inner voice – is begging you not to do the film. It was a really unique circumstance that he was in, and I felt such compassion for him. … I thought it put a terrible, really unfair strain on Benedict.”