Buried treasures

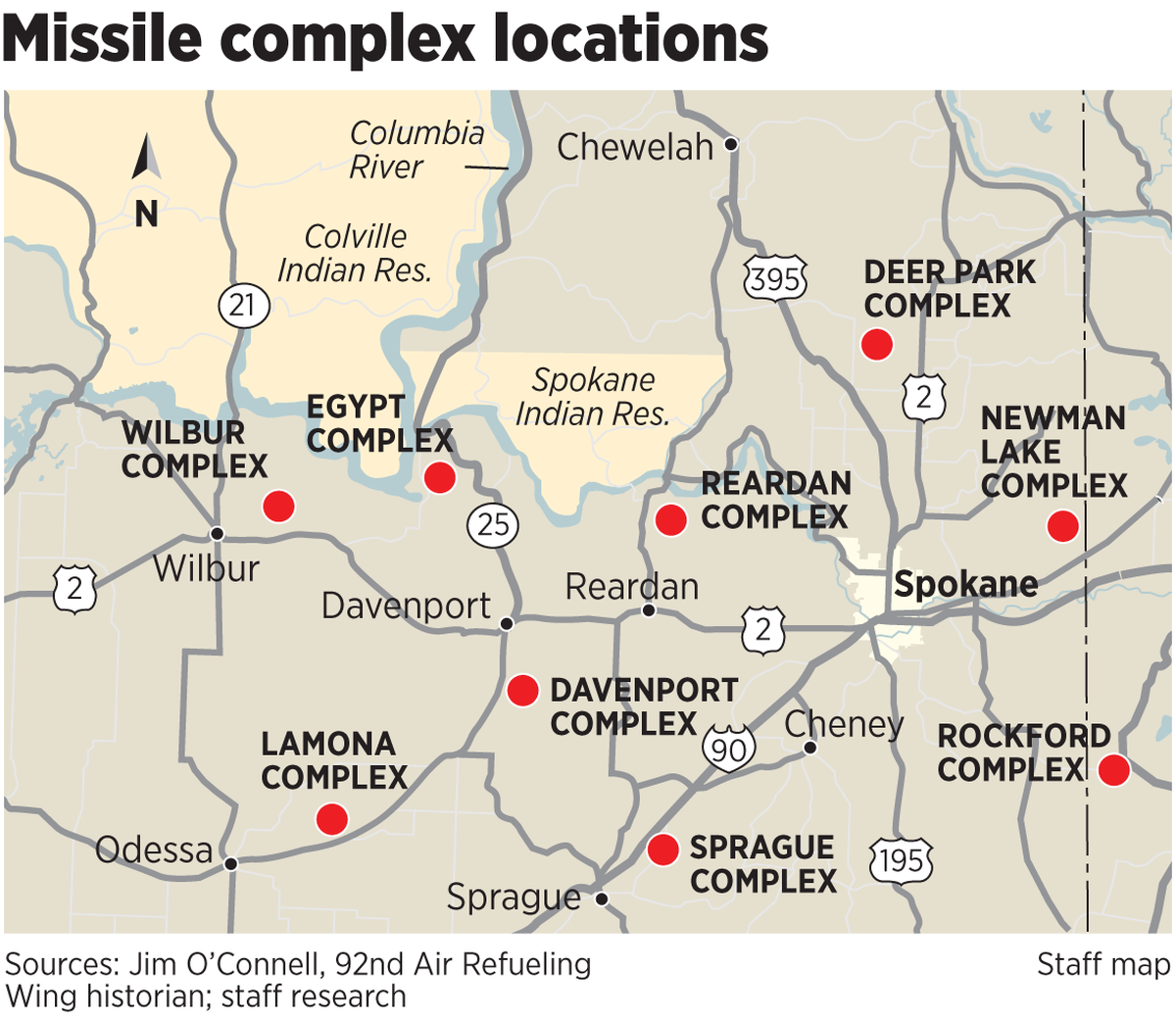

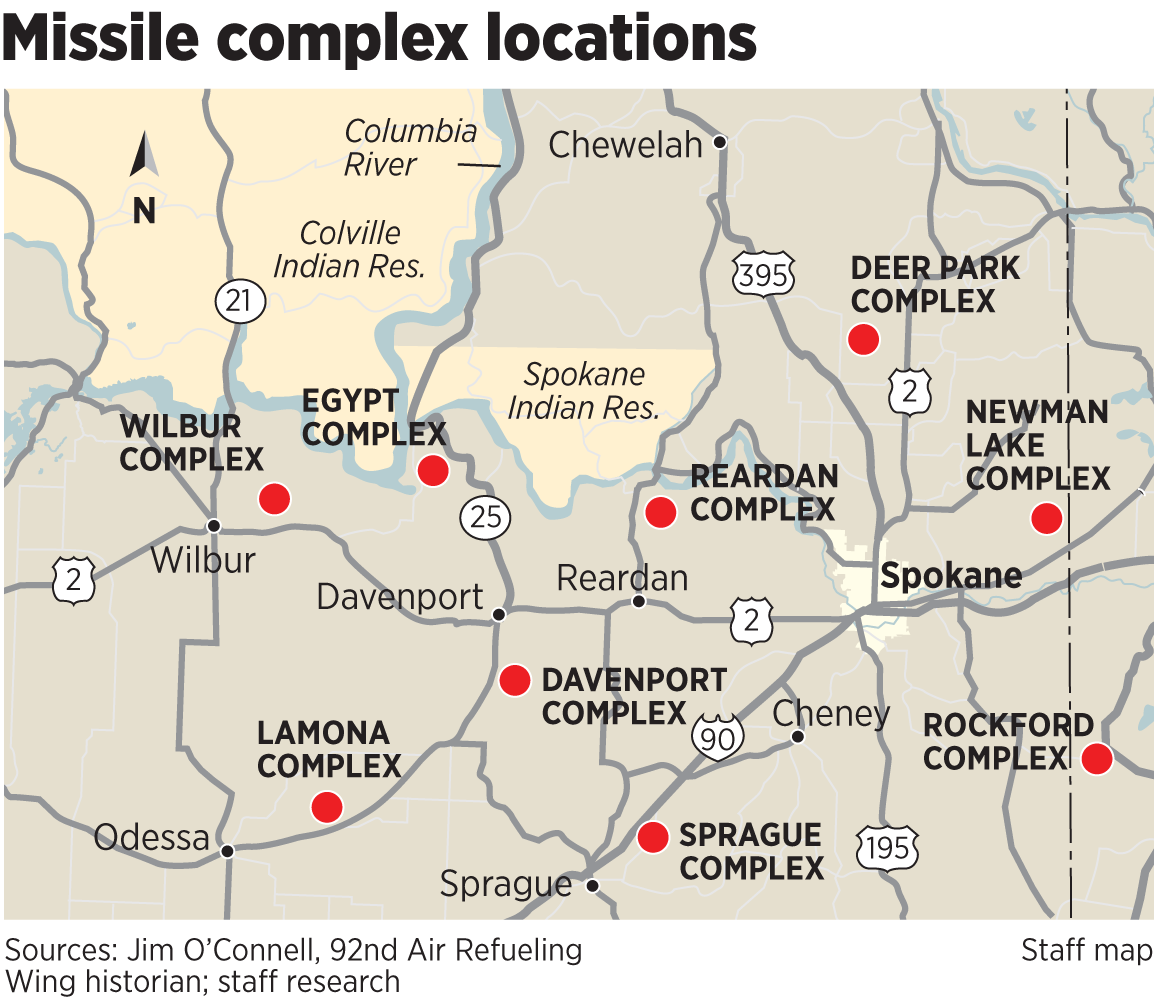

Nine missile silos near Spokane sit abandoned or fill nonmilitary uses, but in the fall of 1962, their nuclear warheads were poised to strike

Back in 1961 the U.S. Air Force, without any attempt at secrecy or stealth, hauled nine long-range ballistic missiles by truck from California to Eastern Washington.

The trucks carried 82-foot-long Atlas E missiles that ended up parked inside heavily reinforced underground sites. Each missile was later armed with a 4-megaton nuclear bomb, ready to be launched.

Eastern Washington communities – including Spokane, Deer Park and Davenport – greeted the weapons caravans like a victory parade. That patriotic fervor, historians say, was part of the Cold War-era mindset fueled by nuclear dread and national pride.

More than 50 years later, those nine underground Atlas sites are largely ignored except by curiosity-seekers and military history buffs.

Most people don’t even know the buried bunkers exist, said Mark Kramer, whose family owns one of the 20-acre sites. It sits amid parched desert about a dozen miles from the family’s home near the community of Lamona in Lincoln County.

The Kramers store farm equipment inside the facility (below, right), which was active from 1961 to 1965 as part of the U.S. Air Force’s 567th Missile Squadron, assigned to Fairchild Air Force Base.

Constructed at the time for more than $4 million each, the silos were designed to withstand a nearby nuclear bomb blast and deliver a hydrogen bomb to a distant target.

The nine sites relied on crews of five airmen working 24-hour shifts, with three redundant communications systems connecting them to the Strategic Air Command. Instead of storing missiles vertically, the nine Atlas E locations held a single missile in a horizontal room, called the coffin.

The crews lived and worked in separate underground rooms connected to the coffin by long tunnels.

Today, all but one of the nine sites associated with Fairchild are privately owned.

At the Kramer family silo (below, left), at the end of a sloping concrete ramp, a 16-inch-thick metal door measures 15 feet wide and 17 feet tall. It stays closed except when Kramer drives the family’s trucks or combines into or out of the main bunker or coffin, which extends nearly 24 feet below ground.

Except for the ramp, the silo is nearly all underground, with only the large iron lid that covered the coffin visible above the surface.

The Kramers have owned the site since 1969, when Mark’s father, Bob Kramer, bought the abandoned site for $2,500.

A nearby second, smaller door also made of heavy steel was the entry for the site’s crew members.

The door’s padlocks are pocked with bullet holes from attempts to get inside.

“If people would just ask us, we’d show them ourselves what’s here,” Kramer said. “Maybe we should have a once-a-year open house, so people don’t keep trying to break in.”

Altogether, the Defense Department built 27 such Atlas E sites. Those missile crews only went on full alert one time, during the 13 days of the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Most sites used for storage

In 1965, the Air Force decommissioned the Atlas E sites and replaced them with more modern missiles at other locations across the country.

The original components – thousands of tons of wiring, plus steel, copper and iron fixtures in the sites – were hauled off long ago and sold for salvage.

Their current owners mostly use the silos for weather-resistant storage or as a secure location for personal property.

The exception is the best-preserved of the nine sites, near Reardan (see map, right). That fully equipped site is run by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. That federal agency, which took over the role of the defunct Bureau of Mines, uses it for storage and occasional research, a CDC spokeswoman said.

Two of the other eight sites are used by farmers to hold equipment. Another site, in Lincoln County, has been converted into the owner’s residence.

Because the sites are below ground and have thick concrete walls and floors, they still have some value for potential buyers, said Ed Peden, a Kansas-based operator of the website MissileBases.com, which lists abandoned missile locations for sale nationwide.

“Some people decide they’ll grow mushrooms or other crops in them” because they’re often dark and dank, Peden said.

One Atlas E base in Kansas supposedly housed the country’s largest illegal LSD lab at the turn of the century, Peden said.

Also looking to buy sites are “preppers,” people who want off-the-grid storage for food and supplies so that they’re prepared to survive widespread economic upheaval, he said.

Peden has helped sell about 55 former missile sites, including the Newman Lake Atlas E site, which sold in 1999.

Peden and his family bought a former Atlas site in eastern Kansas in 1983, paying $40,000. It took him 10 years to convince his wife they should move into the site, he said.

While he acknowledges he’s involved in promoting sales of such locations, Peden said they will continue attracting more interest over time. “These are some of strongest structures built,” he said.

“I think of them as the counterpart of European castles. To me, the silos are 20th century castles,” he said.

Six sites in Lincoln County

Much of the history of the region’s Air Force missile sites has been collected by the Spokane-based Honor Point Military and Aerospace Museum. That group has compiled a large volume of photos and documents tracking the region’s role in preparing for a war no one wanted to see start.

Those records have been studied by the Kramers and others who have purchased some of the other Atlas silos.

In addition to the Kramers’ site, Lincoln County has five other former Atlas locations. One near Wilbur is used by a farmer to grow seedlings, said Dick Mellor, former Air Force missile crew member.

Another site, near tiny Egypt, Washington, sits empty, said Mellor, who was a ballistic missile analyst – a general troubleshooter.

Spokane has two sites. One in Deer Park, a short distance from the Deer Park Airport, is used by Northwest Energetic Services, a company that provides explosives for construction projects. The other, near Newman Lake, was purchased in 1999 by San Francisco resident John Oleg Konings. Konings has considered turning it into a museum or some other commercial use, but it currently sits vacant.

About 20 miles from the Kramers’ site is the Atlas No. 6 site, between Harrington and U.S. Highway 2. Its owner is Peter B. Davenport, the 66-year-old director of the National UFO Reporting Center. The site once belonged to long-haul truck driver Ralph Benson, who was convicted in 2004 of murdering a state auditor and dismembering the body.

Davenport bought the site from Benson’s sons in 2006. Since then he’s used it to hold records related to his UFO research.

Davenport said he gets frequent requests for tours, which tells him interest in that period of U.S. military history must be high. “Most people tend to romanticize the ownership of an ICBM site, without recognizing just how big they are and how much maintenance they require,” Davenport said.

Idaho’s lone Atlas site is in Kootenai County between Rockford and Worley and owned by a local family who use it to store farm equipment and supplies.

The one government-owned site at Reardan is the best preserved. After the other eight were closed and sold, the Reardan facility was leased to the Bureau of Mines’ Spokane office. The missile facility is listed with the National Register of Historic Places and is also listed on Washington Heritage Register.

Rumors have swirled around the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health site, with some skeptics saying they find it strange a mining safety agency would locate its research in a site that isn’t very deep. The Kramers say they’ve heard speculation the Reardan site is a repository for biological samples being studied by the CDC.

Michael Jenkins, an official with the agency’s Spokane office, said those rumors are inaccurate and unfounded.

15 minutes to launch

Mellor, who’s now 81, said he doesn’t go out often to visit the Atlas sites, where he once served as a technician and review officer, testing other members of the missile squadron. Once a week, every crew had to lift the rocket from its horizontal frame and get it ready for a possible launch.

“It’s kind of scary going into one of them now,” Mellor said. “Because, really, we were 15 minutes away from letting one of those missiles go. That would have changed the world as we know it.”

In 1962, as the Cuban Missile Crisis started, Mellor was a member of the 567th “standboard” team, which made regular visits to the nine sites, testing crews and making sure the missiles functioned normally.

As the crisis deepened, all U.S. missile sites were placed on full alert. But Mellor said only the nine local Atlas missiles were retargeted to Cuba.

“The other missiles, in Kansas or Missouri, were too near Cuba; they’d overshoot Cuba. So they had our nine Atlases all aimed at Cuba,” he said.

If the order came, the crew started a 15-minute countdown. The 42-ton steel coffin lid would slide over and the missile would be lifted to upright position, followed by loading kerosene and liquid oxygen into the fuel tanks.

If the countdown reached the “commit” point, at 59 seconds and counting, there was no way to stop the launch, he added.

“We listened to reports from SAC (Strategic Air Command) throughout the whole thing, and we had to stay underground the 13 days,” Mellor recalls.

He worried about his wife and three young sons who were on the airbase but would have been evacuated if war broke out, he said.

If the order to launch had come down, Mellor said it would have happened.

“Oh yes, without a doubt. Without a doubt. That was our job.”

The day the crisis was over, Mellor and the other crew teams left the sites.

“I got the hell out of there and took a shower,” he said.