Trail cameras provide deeper insight into wildlife habits

A remote trail-cam photo is worth a thousand words about the wildlife we don’t see while recreating in the great outdoors.

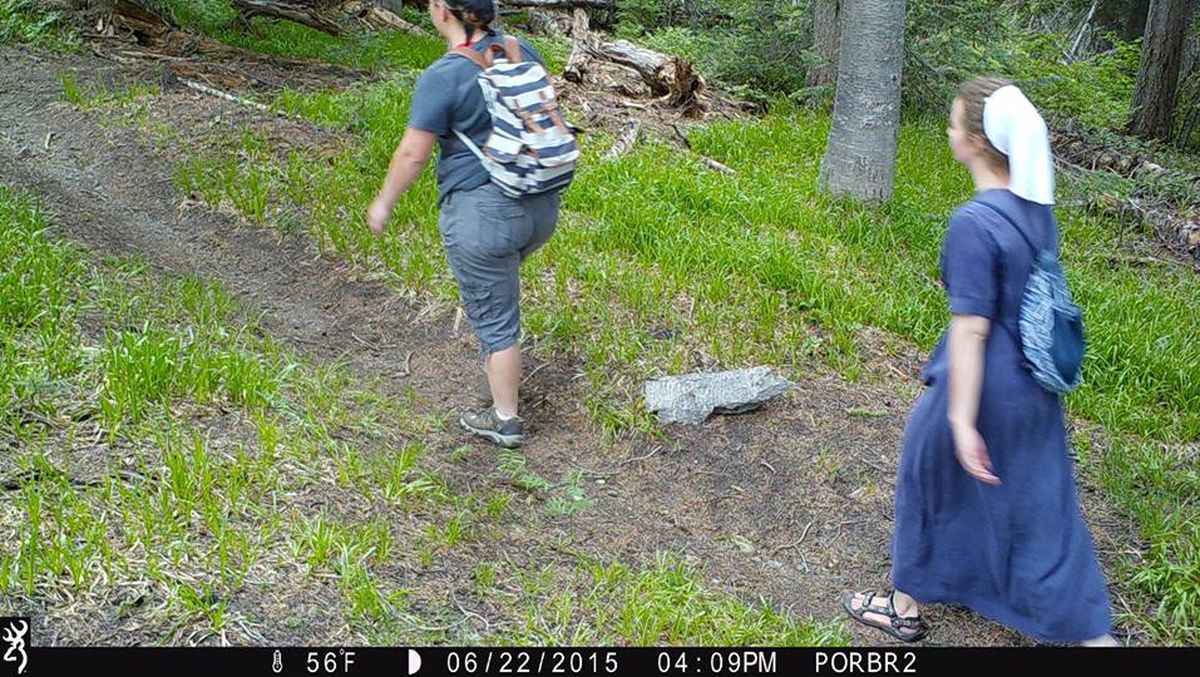

A group of female hikers triggered a motion-activated sensor of a camera put out in Pend Oreille County by wildlife biologists.

Four minutes later, according to the time stamps, a black bear walked up to the trail where the women had passed.

Later, the women are photographed hiking back out the trail. No problem.

“I’m assuming they had no encounter with the bear and likely didn’t even know it was there,” said Bart George, one of the Kalispel Tribe’s biologists. George is monitoring several cameras in a cooperative study with Washington State University on Canada lynx.

Nobody knows better than a wildlife biologist how many critters go unseen by humans despite their close proximity.

Woody Myers, a Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife research wildlife biologist, recalls an example while monitoring radio-collared elk during a 1990s study in the Blue Mountains.

“We were tracking an elk with our telemetry gear from a road when we ran into two elk hunters,” he recalled. “They were wondering where all the elk were because they hadn’t seen one in days.

“At that very moment, we were getting a signal from an elk that was less than a half a mile away.”

Wildlife scientists would be no better off than experienced hunters without high-tech tools, Myers said.

“We’ve been studying deer for decades, but only recently have we identified a major whitetail deer migration route – and it’s within a half a mile or less from a paved state highway,” he said.

The boost in knowledge gained by GPS satellite collars over the older less-expensive radio-telemetry collars is huge, Myers said.

Radio-collared animals are tracked in the field with hand-held antennas. Usually this is done from aircraft that fly only in good weather.

GPS collars allow the researcher to monitor the animal on a computer from an office and see not only where it is, but also where it’s been.

“A Canadian researcher had done considerable research on a radio-collared grizzly bear and had flown almost weekly to get the bear’s location and document its home range.” Myers said.

“When he had to replace the collar, he upgraded to GPS and found out what the bear was doing on the days between his monitoring flights – and it was significant.

“Turns out, that bear was heading out on sojourns of 40 miles and then returning to the same general area. Those movement patterns were not being picked up by the biologist in his earlier research.

“That illustrates how incomplete information could lead you down the wrong path of how a bear is using the landscape.”

Similarly, trail cams with infra-red capability are giving scientists, hunters and even homeowners keen insight into what’s wandering around every day – and night.

“A lot goes on while were asleep,” George said. “In fact, a lot of wildlife are most active during the night.”

But the trail cameras are always awake, as long as you keep them loaded with charged batteries, he said.

And assuming they aren’t stolen.

“Every hiker or hunter has a story about turning back on a trail and finding the track of a cougar or some other animal in their own boot or snowshoe track,” George said. “But having photo evidence showing details about the animal gives you more to work with.”

Experienced hunters and trappers can read a landscape for sign, such as tracks, scat and clues on the ground and vegetation the animal had disturbed or eaten. The landscape is like a giant crime scene. Evidence is everywhere.

“But even the best tracker needs the right conditions, like fresh snow or the right ground conditions,” George said.

“We have cameras out in rocky wilderness mountain passes that caught photos of (woodland) caribou last year,” he said, noting that fewer than two dozen are known to be wandering in and out of the United States in the Selkirk Mountains.”

“It’s all rock in those passes. The cameras gave us a lot of information we couldn’t have gotten otherwise.”

The Kalispel Tribe partners with WSU, the state Fish and Wildlife Department and other agencies to share information from trail cameras on a wide range of wildlife, he said.

“We have 18 cameras out for a grizzly bear survey and about 10 cameras out for the lynx project with WSU,” he said.

“Other cameras are out there looking for wolves in areas not yet known to be home range for documented packs. If we get a picture of one, we forward the information immediately to WDFW.

Sometimes a photo will distinguish a lactating female and it always shows the wolf’s color, which is important information for monitoring.

“I can’t imagine how difficult it would be to monitor and manage wolf recovery without remote cameras,” George said.

The best wildlife tracker in the world can’t be in the woods looking 24/7 for months at a time.

The best tracker can’t be at numerous places at one time to compare the high-tech advantage of a biologist or hunter who has put out several or perhaps dozens of cameras.

“Trail cameras are a super useful tool,” said George, who also is an avid hunter.

“But I’ll tell you this: People nowadays can’t hardly find anyplace to hike or roam around and be completely sure they’re not being photographed by a camera.”

That might make you think twice about the next occurrence that tempts you to into poaching, trespassing or, say, skinny dipping.

Wildlife is under constant scrutiny out there, and so are you.

Contact Rich Landers at (509) 459-5508 or email richl@spokesman.com.