Yard work: Spokane hopes to turn long-neglected area into industrial hub

A motorcycle drives down unpaved East Central Avenue in The Yard, an industrial part of northeast Spokane that has sat polluted and largely abandoned for 50 years. (Dan Pelle)Buy a print of this photo

Randy Hastings’ drive to work takes him to the east side of Spokane, over the dirt roads of Hillyard to the forgotten part of town where he’s kept his business – R&R Heating and Air Conditioning – since 1987. He drives past empty lots, decrepit homes, a trailer park, warehouses, laboratories and large grocery store distribution complexes. The roads shift from paved to graveled, new to old, from being bordered by sidewalks and landscaping to a fuzzy edge of overgrown weeds.

Standing outside the empty building his business outgrew a decade ago, but which he still owns and leases out, Hastings points to a fire hydrant the city made him pay for, next to a road he has unsuccessfully asked the city to build for years, and at a house he’s pretty sure is a drug front.

The sullied reputation is what brought Hastings’ business here, though not directly.

“Land was cheap,” he said. “It’s Dogtown, you know.”

This area generally east of Market Street and north of Empire Avenue has long been called Dogtown, a recognition of its rough past and hardscrabble present, though the term is offensive to some locals.

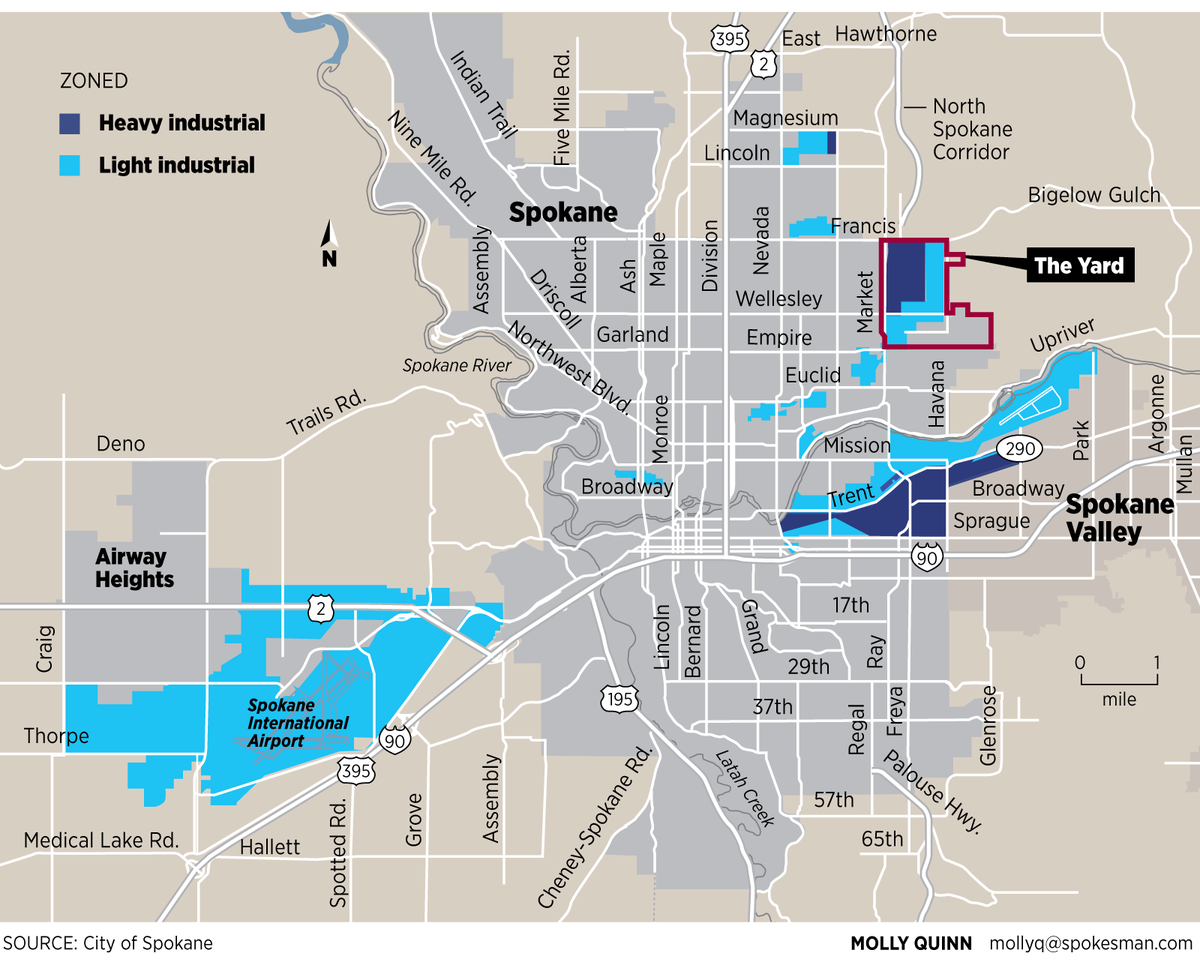

But the city of Spokane is intent on remaking this part of town, and has even bestowed on it a new name: The Yard. The vast majority of the property in the area – including the parcels that have homes and neighborhoods on them – is zoned industrial or light industrial. A BNSF rail line still cuts through the area. In coming years, the North Spokane Corridor will run along the area’s western flank.

In its vision, the city sees The Yard as a new center of industrial output for Spokane, a hub of regional and national trade, a home for blue-collar jobs and workers making good pay. Kendall Yards is a formerly polluted site that was successfully transformed into a living and shopping center. Officials see The Yard doing the same for industry.

But first, a vast cleanup project must be done.

Number of brownfields unknown

By the time the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was created in 1970 and began regulating the toxic output of American companies, Hillyard’s industrial bustle had largely died and left behind environmental hazards throughout the area. The state’s Toxic Cleanup Program confirmed contamination on a few sites – eight of the 978 parcels in The Yard are known to be polluted. The state Ecology Department suspects an additional 183 parcels are polluted by contaminants that were never regulated, quantified or tracked.

That’s the first difficulty in cleaning up The Yard – finding the pollution. No one really knows how many polluted properties are in The Yard, or how many are in Spokane for that matter.

One Ecology Department catalog of Spokane brownfields – potentially polluted properties that have development possibilities – lists 2,976 such parcels within the city.

But Sandra Treccani, a hydrogeologist in the Ecology Department’s toxics cleanup program, doubts the number is that high. Instead, Treccani, who works in Ecology’s Spokane office, urged a better understanding of the unknowable nature of an unstudied brownfield.

“Sometimes they aren’t even impacted, but there’s the perception that they’re impacted. That’s often in the definition of a brownfield – the perception of contamination,” Treccani said. “If in the ’50s there was a service station and there might be some contamination, it’s a brownfield.”

Treccani said buyers shy away from properties that are brownfields. Even if there is absolutely no pollution, analysis of the property is demanded by real estate agents and banks. If contamination turns up – even if the property owner is not responsible for it being there – they own it.

“Even if you never dumped a bucket of paint on the ground, or refilled your car wrong and shot a bunch of gas on the ground, it doesn’t matter,” Treccani said. “If you own the property, you’re liable. That’s why people who buy property are always a little afraid.”

That’s what Teri Stripes, a city planner who is leading the city’s efforts at The Yard, is trying to avoid.

In the past few years, as the city has turned its gaze to The Yard’s 500 acres, Stripes has helped build programs and garner designations for the area to help mitigate the contamination and burnish Hillyard’s reputation.

Listening to Stripes talk about revitalizing The Yard sounds as complicated as NASA’s preparations for the recent Pluto flyby. Still, she has a clear vision on where the city wants to go.

“I don’t think talking about what it will look like is as important as how it will function,” she said. “We want it to be a job generator, much like it used to be in its heyday when the rail cars were being built there.”

Spokane Mayor David Condon echoed Stripes.

“If you look at the economic vitality of our area, manufacturing is the No. 1 way to do that,” he said. “Typically manufacturing companies do pay higher. They do have sick leave. They do have benefits. … You’re in the $15-plus per-hour range. You’re talking long-term careers. And what’s exciting is a lot of it is what was there. The railroad was in that category.”

Scott Simmons, developer of the city’s business and developer services division, said better jobs would reverberate in the surrounding neighborhoods.

“How do you not only bring jobs, living-wage jobs, but how do you bring the median household income up,” Simmons said. “We recognize that you have to have communities that are desirous to live in; that’s really what helps bring median household income up. Knowing that, The Yard is a place where we’re trying to encourage development, and knowing that a lot of the skilled labor around there could have access to those jobs allows for that reinvestment back into homes and improving the condition of where they’re living.”

As city officials recognize, that’s a ways off. To get to a revitalized Yard where industry hums above clean soil, polluted properties have to be identified and mitigated, the city has to build infrastructure to support industry and – most crucially – private interests must locate there.

“We’ve done the foundational planning work, so we know what our market is and we know what our needs are at a very high level. At a 30,000-foot level,” Stripes said. “Now we need to drill down and look at specific sites. It’s going to take time, but I think that you’re already starting to see what’s going on.”

What’s going on began in 2010, when then-Mayor Mary Verner attended the Market Street ribbon-cutting and noted the work to revitalize Hillyard would continue, but only with the help of the community. An advisory board was created, focused on rebuilding Hillyard’s lost industries and concurrent jobs, which led to the formation of the Northeast Public Development Authority. In 2012, Mayor David Condon appointed members to the NEPDA, and since then work has continued apace.

The city and NEPDA won a state Department of Commerce grant of $110,000 in 2014, as well as a U.S. Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration grant of $22,000 the same year. The money was used to create three reports issued this year: a heavy freight-user analysis, an infrastructure assessment and needs analysis, and a brownfields plan.

In May, the City Council approved the creation of a Brownfield Opportunity Zone, overlapping The Yard, with the NEPDA members serving as its board of directors.

The Hillyard opportunity zone is the first of its kind in the state. In fact, the ability to create such a zone was made possible just two years ago, when the state Legislature reformed the Model Toxics Control Act. The legislation explicitly directed the Ecology Department to prioritize cleanup projects in brownfield opportunity zones before projects outside of established zones.

That means The Yard has better access to the $764 million in remedial action grants that will be distributed by the state in the next 10 years, which can be used for assessment and analysis of brownfields.

Such initial groundwork has begun to pay off. In a three-month span this spring, the EPA awarded $600,000 toward assessment and cleanup in The Yard. The city will use these federal dollars to evaluate at least 16 properties and create cleanup plans for a handful of others.

Stripes said two properties already have been identified as “catalytic” – with hope, they’ll get cleaned up and marketed, drawing in the first developers and knocking over that first domino.

The first is a 10-acre parcel owned by the city and used for decades by the streets department for storage. It’s called the Ranch. The other property is 25 contiguous acres of light industry-zoned property off Rich Avenue next to the future North Spokane Corridor. This property is very likely dirty and has no infrastructure.

Riverfront Park a brownfield, too

There’s plenty of other funding the city is hunting.

There are groundwater and drinking water grants. Integrated planning grants can be won, and the $200,000 they deliver need no matching funding from the city. Revolving loan funds can be established, allowing something of a feedback loop of money for projects in The Yard.

Seth Preston, Ecology’s spokesman, said there is “no clean, simple answer” to how much money the department has for brownfield cleanup. Mark McIntyre, an EPA spokesman, said something similar.

But, Treccani assured, “There’s a bunch of money.”

Regardless of how much money is available, as other cleanup projects in Spokane show, the cost of remediation varies.

Kendall Yards, a former rail yard on the north side of the Spokane River, had 223,000 tons of contaminated soil removed at a cost of $2.4 million in 2005 before becoming perhaps the most exciting redevelopment in recent Spokane history.

Remediation for the soil below just one building in the University District, WSU-Spokane’s Biomedical Pharmaceutical Sciences Building, cost $1.2 million in 2010, which the university paid for without assistance from state or federal agencies, said Rusty Pritchard, senior project manager for the campus.

The Spokane Public Facilities District has spent more than $4 million on cleanup since 2004 below its various properties, including the Convention Center, according to its CEO, Kevin Twohig.

And no one knows how much was spent on cleaning up Riverfront Park. When the environmental-themed World’s Fair came to town in 1974, Spokane had spent years converting the polluted, industrial city center into the bucolic park known today. It was another 20 years before the EPA coined the term “brownfield” to describe polluted lands that have potential for redevelopment.

“When I give people a tour of Riverfront Park, I call it ‘The brownfield before brownfields existed,’ ” Treccani said. “It was the first one because it was the World’s Fair where they focused on environmental issues. Who knows how good of a job they did cleaning it up, because the cleanup regulations weren’t in place then. But they turned it into the gem of the city.”

‘We’re going to have to grease the wheels’

Treccani calls these examples – Kendall Yards, Riverfront Park, the U-District and the Convention Center – the “low-hanging fruit.”

“Those are the easy ones,” she said. “Like Riverfront Park. It’s contaminated but it’s got huge potential. It’s right in the very middle of downtown. You’re not going to need to give that a lot of help to get that going. There’s going to be a developer who is all over that.”

Treccani said these “easy” ones are done. Now, however, the fruit’s not so easy to pick.

“This is the world we live in now with brownfields,” she said. “It’s an OK property. There might be some benefit but we’re going to need to add a little something to the pot to get a developer interested. We’re going to have to help answer some questions for them. We’re going to have to offer them a loan. We’re going to have to grease the wheels.”

She wasn’t speaking about The Yard, but might as well have been.

This summer, the city created an incentive program aimed at jump-starting private development, waiving fees and providing funding in a handful of targeted areas such as East Sprague Avenue, the West Plains and the University District.

It’s no coincidence that The Yard is one of those areas, with $9 million worth of available property for sale – albeit with no major buildings and limited access to infrastructure.

In the past year, Alcobra Metals has located in The Yard, joining the two dozen other companies already in place, which include Hi-Rel Laboratories, Loomis, Powers Candy & Nut, City Glass and Pizza Pipeline’s corporate headquarters. If things go well, the city will sell the 10-acre Ranch, knocking over that first domino.

Hastings, who owns R&R Heating and Air Conditioning, isn’t so sure The Yard is primed for takeoff. In the nearly 30 years he’s operated his business in Hillyard, it’s grown from two employees to almost 70. He built a building, outgrew it, built another and then expanded it to include a second story, warehouse and machine shop.

Of course, he wants this part of town to improve, to allow other business owners to have the success he’s had. But even the most basic infrastructure, including electrical infrastructure to support heavy industry, has vexed him.

“We need roads,” he said. “There are more dirt roads here than in any other part of Spokane. We need three-phase power. We’ve got to get infrastructure.”

Asked if he was skeptical about a bright future for The Yard, Hastings said he wasn’t. Instead, he spoke more of patience.

“It’s going to happen. It’s just not going to happen fast,” he said. “It’s a long, drawn-out process. It’s going to take 20 or 30 years.”