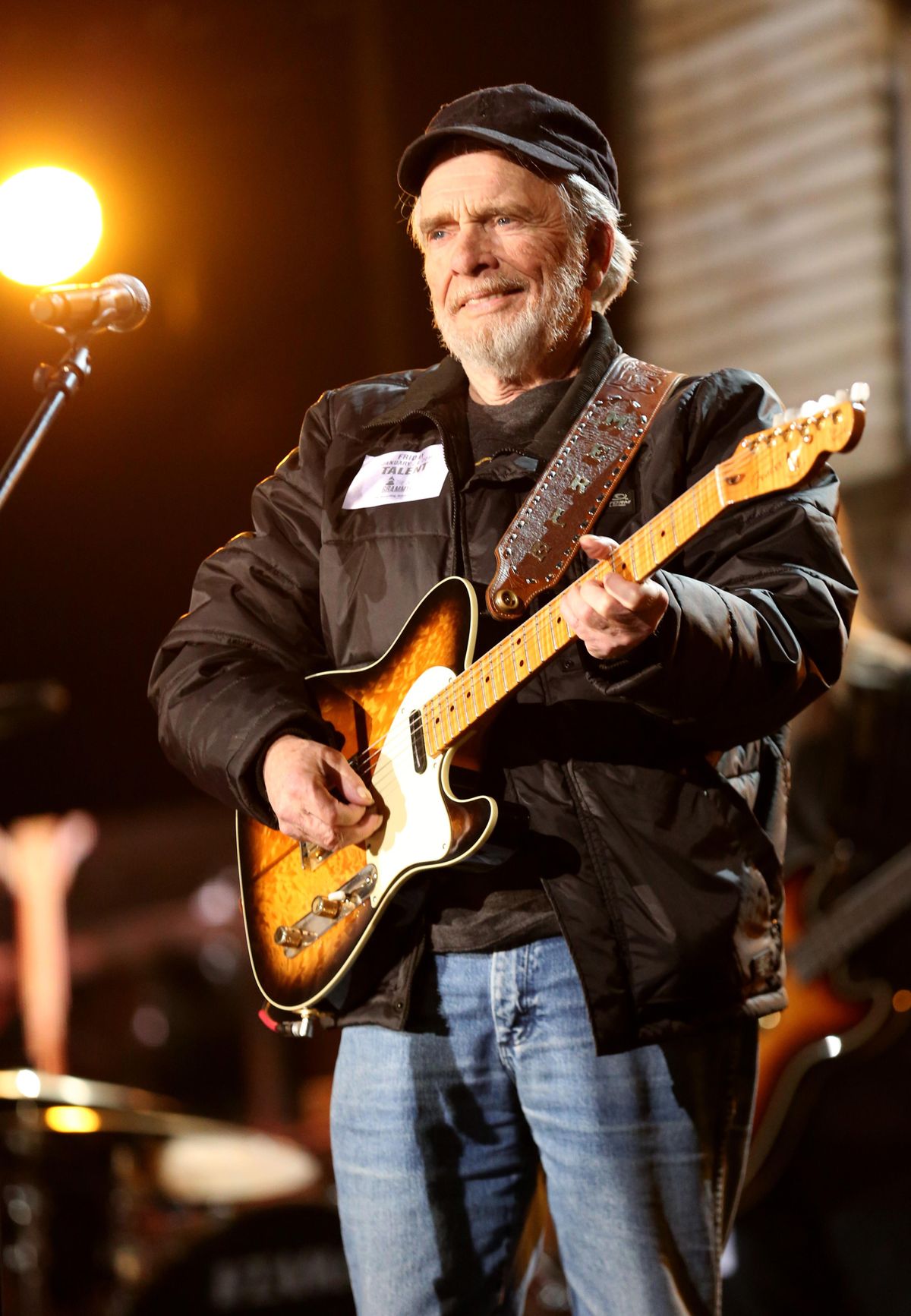

Haggard’s life is certainly biopic-worthy

The death of Merle Haggard last week marked the end of an era, or at least a piece of an era. At a moment when singers were beginning to use music as a class-conscious weapon, Haggard wielded it with a sharp potency. Listening to “Okie From Muskogee” with the hindsight of 2016, one is struck how much, beneath its laid-back rhythms, Haggard is seething about the protest movement of the 1960s. It’s a song that’s angry about anger, really.

The Bakersfield Sound pioneer’s back story was also unique – jailhouse escapes, violent love triangles, colorful blue-collar jobs (potato-truck driver?). In a modern era when many singers in country music (and other genres) merely wear the garb of the outlaw, Haggard genuinely was one, with a life as interesting as the songs.

You’d think with such an interesting life, a scripted movie might have been made about him. As it turns out, none has. As it turns out further, many of the fascinating country music personalities of the 20th century don’t seem to be yielding especially good movies.

“I Saw the Light,” which opened recently, is afflicted by a certain airlessness. Tom Hiddleston’s Hank Williams is convincing, but the movie never succeeds in being equally persuasive about its subject’s inner life – let alone in explaining why Williams, a musical trailblazer and one of the greatest songwriters in history, really mattered. That robs the fallen-hero tale of much of its power. He’s just one more man about to be done in by his weaker impulses, and there’s little reason for us to care who he is.

A similar issue suffocated “Walk the Line,” which drained many of the class tensions and ironies that made Johnny Cash so intriguing and turned his life into the stuff of love story (and addiction) genericism. Cash’s embrace by convicts as he’s becoming a successful star is one of several paradoxes at the heart of the musician. But it’s hinted at only fleetingly.

Even when Hollywood attempts to make a movie about a fictional country star, as it did with “Crazy Heart” back in 2009 – and has the creative license to go wherever it wants – it falters. In the filmmakers’ hands, what could have been a story of a dissolute drinker with an ambivalent desire for redemption becomes one more story of a thinly drawn female character struggling to help a genius get back on his feet. (Incidentally, this could also be used to describe “I Saw the Light” and “Walk the Line.”)

Why is it so hard to make a good country biopic? Or, put another way, what is it about the genre that makes so many interesting people become uninteresting on the screen?

Some of this is clearly the result of the movie industry trying to understand a culture that’s foreign to it. Hollywood and Nashville have long been separated by more than just a couple thousand miles. The differences have manifested in some of these movies - which feel like they’re being made by West Coast filmmakers, even those with Southern roots - are taking a view from afar.

And it’s hard to ignore the matter of the songs themselves; when your subject’s work itself is so cinematic, actually making a movie that tops – or competes with – it is never easy.

But another reason, I think, may have to do with the glow of nostalgia. When you’re making a movie about personalities that are of another era, you’re less likely to understand the complexities of the time, or at least more likely to hit notes everyone can understand – alcoholism, the power of a good relationship. One reason “Straight Outta Compton” worked so well is because many of the people it was about are still vibrant today, and the issues the musicians faced are still relevant today. So the movie felt textured, and real too.

This is possibly why country music stories used to be so good. “Sweet Dreams,” in 1985, told of a Patsy Cline whose life had been cut short just two decades before. The standard of the genre, 1980’s “A Coal Miner’s Daughter,” was made when Loretta Lynn was still very much in her prime; the memoir on which it was based had been published just four years before. When a young Sissy Spacek and Tommy Lee Jones could be seen navigating the challenges of rural Kentucky, it felt powerful and immediate, not a look through a distant, hagiographic lens.

Proximity to one’s subjects isn’t enough on its own to make for a great biopic, of course; there are plenty of bad biopics about recent figures. But it may help eliminate the more formulaic tics. Sure, an addiction/redemption arc is what makes these stories appealing to producers in the first place. But that’s a starting point, not the sum of the tale.

(See how “Amy” – another movie about a thoroughly contemporary musical figure – was able to go beyond a simple compulsion to drink and show more complex psychological and familial forces. Or just see how more sprawling country pieces with more than just love-and-substances on the mind – like Robert Altman’s “Nashville” or, well, Callie Khouri’s “Nashville” – achieve a greater level of drama.)

Josh Brolin recently revealed that he and Jessica Chastain have signed on to make a movie about George Jones and Tammy Wynette. Yet again, country icons with colorful lives. And yet again, one fears a kind of flatness.

“I have a bit of a past and when they were trying to figure out who might be best able to best play George Jones, they thought, ‘What about Brolin? Who’s been to jail in the last 10 years? Let’s pick Brolin!’ ” Brolin told Conan O’Brien. Brolin may have just been making talk show chatter. But given the genre’s history, one worries from such comments that a country music biopic won’t honor the enigma that was its subject.

Jones, Haggard, Williams and so many others lived colorful lives that encapsulated not just their own contradictions but the contradiction of modern America, and what makes it such an intriguing place. One only wishes for a movie that returns the favor.