WSU contributed to groundbreaking detection of gravitational waves

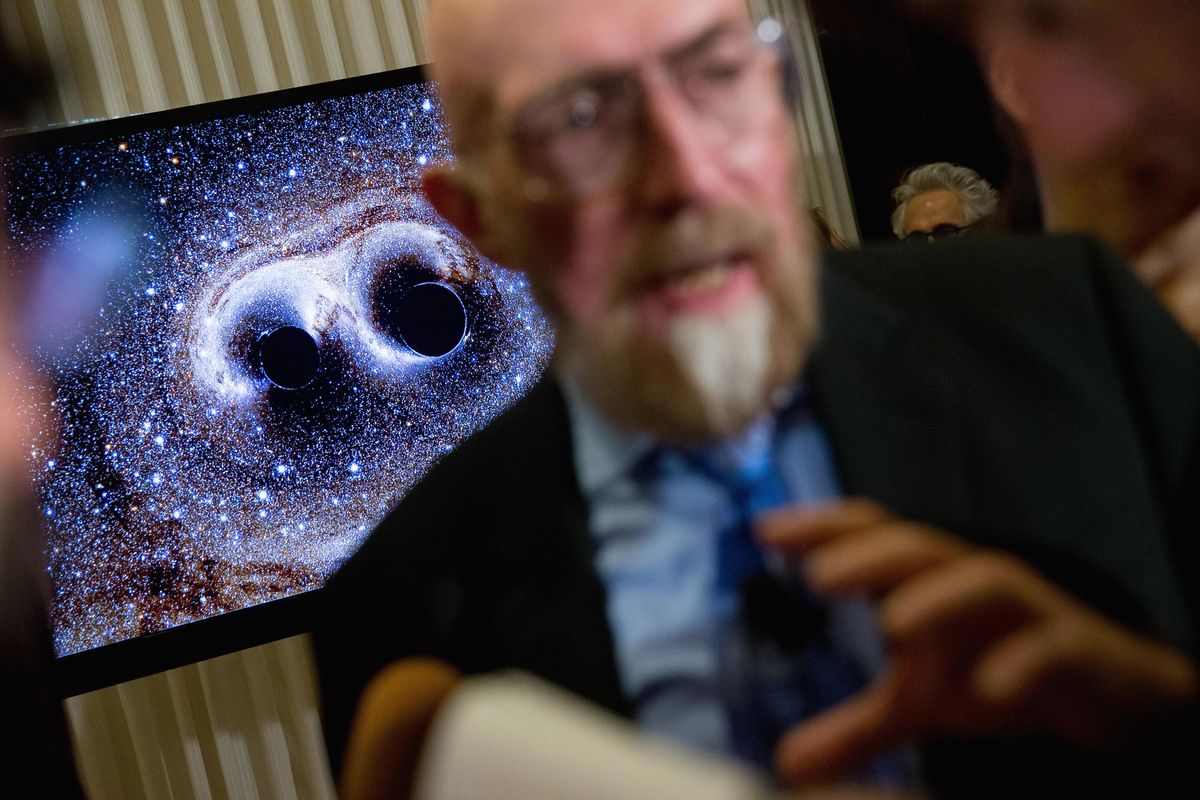

A visual of gravitational waves from two converging black holes is depicted on a monitor behind Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory co-founder Kip Thorne as he speaks to members of the media following a news conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., Thursday, Feb. 11, 2016, as it is announced that scientists they have finally detected gravitational waves, the ripples in the fabric of space-time that Einstein predicted a century ago. The announcement has electrified the world of astronomy, and some have likened the breakthrough to the moment Galileo took up a telescope to look at the planets. (Andrew Harnik / Associated Press)

Professors and graduate students from Washington State University were among more than 1,000 researchers involved in the worldwide effort to detect gravitational waves and confirm Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity.

The announcement came Thursday that researchers had recorded the sound of two black holes colliding a billion light years away, using massive L-shaped antennae in Hanford and Livingston, Louisiana. They claim to have detected a ripple in space-time that was emitted as the two black holes approached and rapidly circled one another, violently merging into one.

On Earth, data from the apocalyptic transformation of mass and energy were converted into a brief soundwave, around the note of middle C.

That fleeting chirp was “a dramatic confirmation of Einstein’s theory,” said Matt McCluskey, chairman of WSU’s physics and astronomy department.

The finding marks a historic leap in the search to confirm Einstein’s theory, first published in 1915, which overturned more than 200 years of scientific thinking that centered on the work of Isaac Newton. Whereas previous researchers viewed the universe as static and fixed, Einstein predicted that matter and energy can produce wrinkles in the fabric of space-time.

Until now, no one has been able to measure those wrinkles directly.

“For a hundred years, scientists suspected the existence of gravity waves but never actually observed them,” McCluskey said.

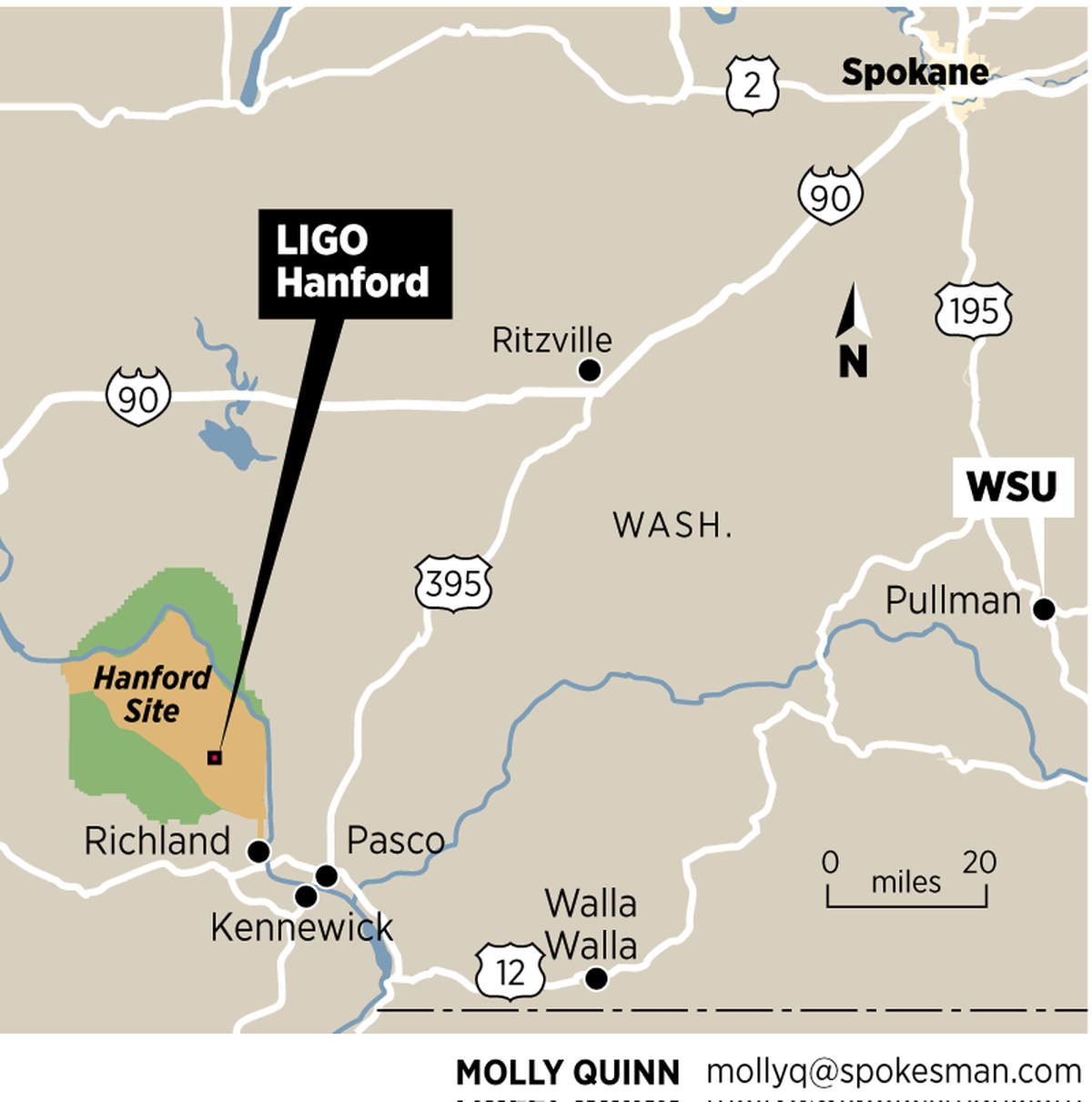

WSU is one part of the worldwide team of researchers known as the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, short for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. Conceived in 1975 by researchers at Caltech and MIT, the LIGO project offers “arguably the most sensitive scientific instruments ever constructed,” according to WSU researchers. The National Science Foundation has poured in about $1.1 billion to the project over the past 40 years.

And now, physicists say, it’s all paid off. The first detection of gravitational waves opens a new world of questions for the scientific community.

“WSU is on the ground floor of this new enterprise, this new era,” McCluskey said.

Following a seven-year redesign and rebuild, the twin LIGO systems in Hanford and Livingston had been calibrated only three days before the chirp was recorded at 2:50 a.m. on Sept. 14. Data was streaming in, although the official observation phase was not scheduled to begin until Sept. 18.

“Luckily it was working with the right sensitivity,” said Nairwita Mazumder, a WSU postdoctoral researcher in mathematical and theoretical physics.

No one was watching when the signal reached the Livingston site, or when it reached the Hanford site seven milliseconds later. A computer recorded everything.

“I was really excited when I heard it’s seven milliseconds because that’s exactly the time difference we expected” between the two sites, she said.

Mazumder, along with graduate students Bernard Hall and Ryan Magee, collaborated with astrophysicists Fred Raab and Greg Mendell, who are WSU adjunct faculty working at the LIGO facility in Hanford. They “contributed to a better understanding of the detector’s behavior, helping it see deeper into the universe,” the university said in a statement.

Physics professor Sukanta Bose and his students helped develop methods of combining data from the twin LIGO detectors to increase the chance of discovering a gravitational wave signal. They relied on prior research by WSU theoretical physicist Matt Duez.

Like all scientific findings, this one is subject to intense scrutiny and attempts at replication. But many scientists are confident in the results. Mazumder said the raw data will soon be made available online.

“You can download the data, you can do your own data analysis,” she said, grinning. “You can try to disprove it, even.”