Dr. George Bagby, inventor and surgeon, dies at 93

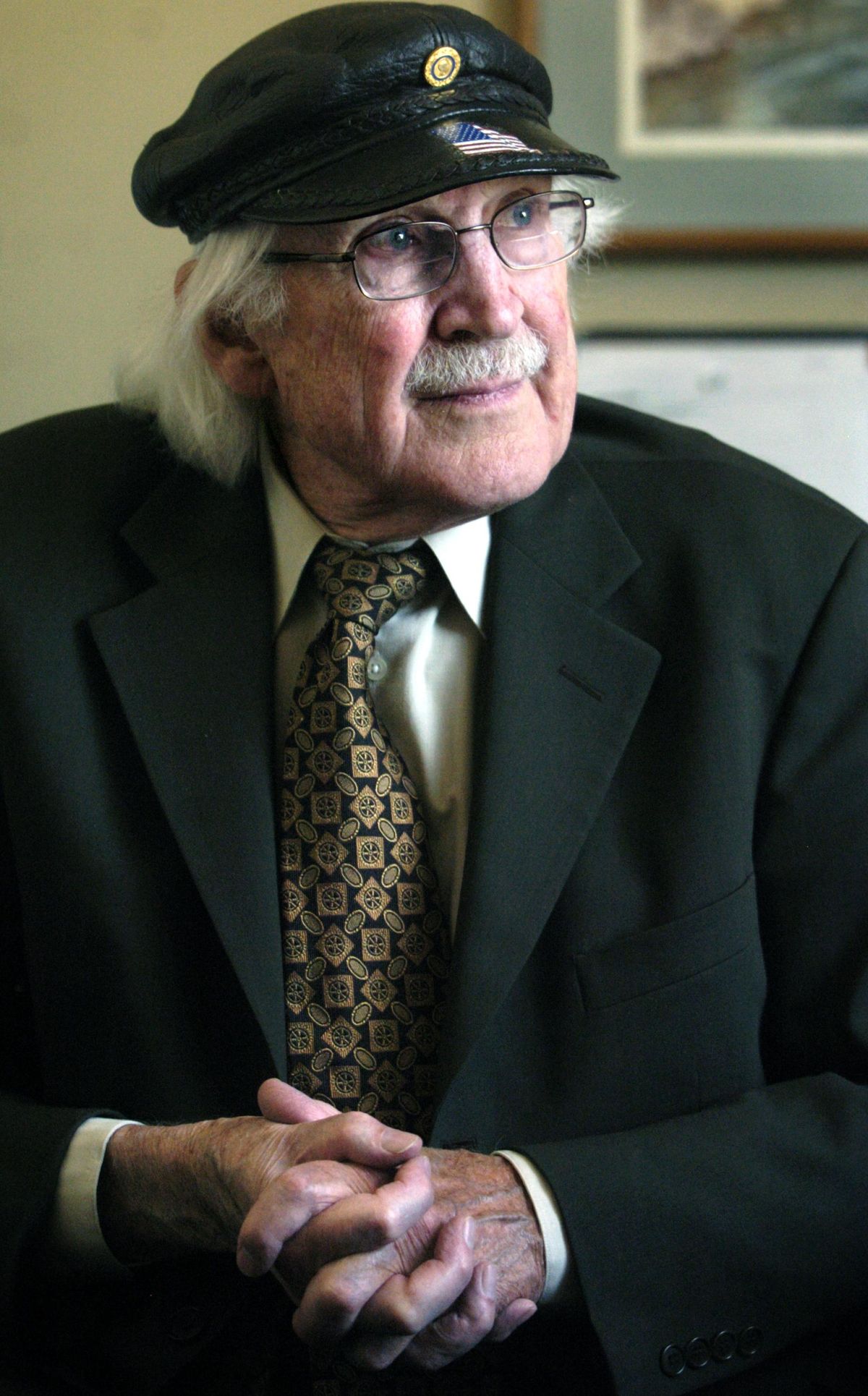

When orthopedic surgeon Dr. George William Bagby II died on Dec. 12 at 93, he left behind scores of patients grateful for his innovative mind and his steady hands.

Considering that Bagby wasn’t a veterinarian, it’s perhaps a little unusual that some of his patients had four legs, and one of them was the famous racehorse and 1977 Triple Crown winner Seattle Slew.

Bagby was born on Feb. 7, 1923, in Waco, Texas. His father died when he was 10, and his mother remarried, moving the family to Minnesota. There, he became interested in medicine as he followed his stepfather, a veterinarian, out on calls.

But he chose medicine and graduated from Temple University, before serving as a surgeon at a hospital in South Korea during the war there.

Bagby got his orthopedic training at the Mayo Clinic and that’s where he came up with the first of his many medical inventions – the “Bagby Bone Plate” – which facilitates healing of fractures.

“It was simple. And genius. George had the ability to do that,” said Dr. Barrie Grant, a personal friend and retired professor of Equine Surgery at Washington State University.

Bagby, who opened a private practice in Spokane in 1956, connected with Grant at WSU in the mid-1970s.

Grant said Bagby felt like human doctors and veterinarians could learn from each other, and they began sending faculty and grad students on visits at each other’s facilities.

Together with equine surgeon Dr. Pamela (Wagner) Von Matthiessen, Grant and Bagby pioneered a spinal procedure on horses with Wobbler Syndrome using a device that became known as the “Bagby Bone Basket” to help fuse vertebrae so the horses could walk steadily again.

Those successful equine surgeries later led to the development of the Bagby and Kuslich (BAK) implant, which is now commonly used in human patients with spine defects.

“We were just doing this as a lark,” Grant said, about the early horse surgeries at WSU. “At the time we were taught that once you damage the spinal cord you couldn’t fix it. But we could see we were clearly on to something.”

In 2000, Bagby operated on Seattle Slew’s neck using an updated version of the Bagby Bone Basket and giving the famous stallion another two years of quality life.

For his substantial contributions to horse medicine, the American Association of Equine Practitioners awarded Bagby its George Stubb’s Award in 2007, the highest honor it bestows on someone who’s not a veterinarian.

“George was just impressive,” Grant said, over the phone from his home outside San Diego.

Grant recalled a trip to a surgeons’ meeting in Lexington, Kentucky, when Bagby entertained an entire restaurant after dinner by playing the banjo and telling jokes.

“He just loved doing that,” Grant said. “Everyone was very relaxed for the surgeries the next morning.”

At Shriner’s Hospitals for Children in Spokane, Bagby arranged fishing trips for hospitalized children to his own well-stocked fishing pond starting in 1999.

“He was very much a gentleman. He was very tall with this white hair,” said Carol Kaczka, manager of recreational therapy at Shriner’s. “And he would just visit with everyone.”

Kaczka said that on the annual fishing trips, Bagby would do magic tricks for the children and, of course, play banjo.

“Sometimes he brought in horses for the kids to ride, sometimes it was a puppeteer,” Kaczka said. “He’d just call us six months before and say it was time to start planning.”

She said the tours began with five children and ended up with nearly 30.

“He brought a lot of joy to our kids,” Kaczka said.

But bringing joy at home wasn’t enough. Bagby joined Orthopedics Overseas and a personal donation founded the two-story Nalta Hospital Bangladesh in 2000. He traveled to the area more than 20 times.

Looking back at his life in 2005, Bagby said he could have retired comfortably on the money he made from his medical inventions, but he chose to continue to see patients and work on fundraising for the hospital.

“I’m not a missionary,” Bagby told The Spokesman-Review. “I’m just interested in providing medical care.”

Rotary International awarded Bagby its Humanitarian Service Award in 2003.

Bagby’s daughter K.C. Wilson said her father practiced until he was 83 – he was named Spokane Physician of the year in 1990 – and never stopped thinking of medicine and inventing.

“He was always thinking of new things, setting new goals,” Wilson said.

He wrote “Spokane in the Rockies,” a song he wanted the city to adopt as its song.

“He took it to the City Council and everything,” Wilson said. “It didn’t go over that big.”

But that was the thing about Bagby: He wasn’t easily deterred.

“He was tenacious. To him, ‘maybe’ meant yes,” Wilson said. “He never took no for an answer.”

Bagby is survived by his four children, Bill and Jon Bagby of Spokane, Mary Murphy of New Zealand, and K.C. Wilson, of Alaska.