Former Idaho Gov. Kempthorne, set for honorary UI degree, now crusades for life insurance, retirement options

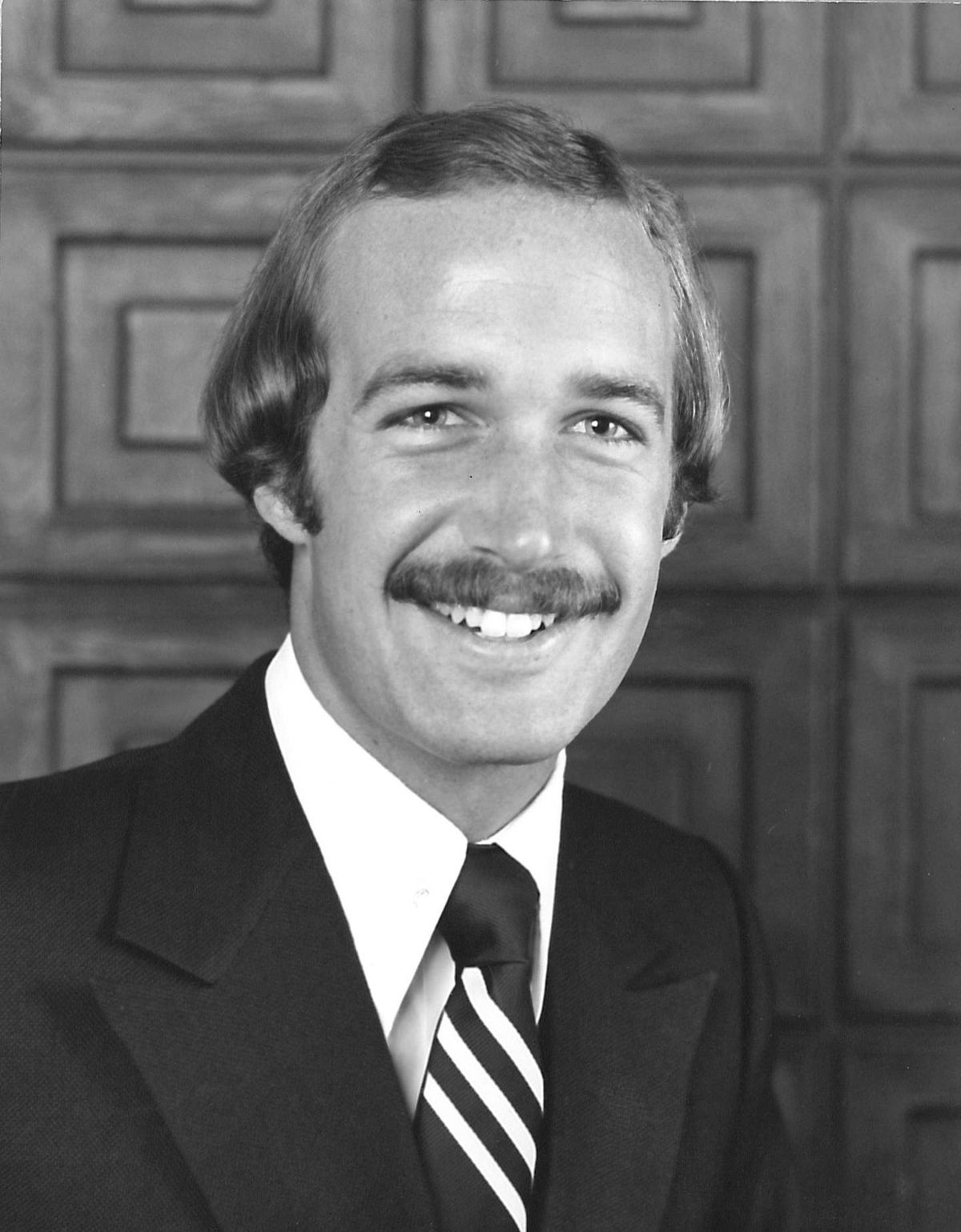

Dirk Kempthorne in 1974, as student body president at the University of Idaho. (University of Idaho)

These days, former Idaho Gov. Dirk Kempthorne is the chief representative of the life insurance industry, traveling the country and the world, giving speeches and representing insurers to the Trump administration, states, international groups and nations.

It’s a role that’s brought the former Boise mayor, U.S. senator and U.S. secretary of the interior – who will receive an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, the University of Idaho, next weekend – back to an issue he focused on as governor of Idaho: The fate of Americans as they age.

“It is possible somebody could achieve the American dream, but then have lived beyond the means that they had set up for themselves, and then find out that there’s no longer resources except perhaps what the government can do for them,” Kempthorne said. “I’m dedicated that people should have dignity their entire life.”

Kempthorne, a Republican, signed legislation in 2001 to grant a 50 percent tax credit for long-term care insurance premiums. In 2004, he urged lawmakers to expand that to 100 percent, which they did. That law’s still on the books today.

In his 2004 state of the state address to a joint session of the Idaho Legislature, Kempthorne declared, “This represents sound tax policy and health care policy. We should be dedicated to guaranteeing the dignity that our parents and grandparents deserve.”

When he chaired the National Governors Association, he made long-term care his top issue of focus.

It’s an issue that hits home for the former governor in a very personal way. In 2003, his elderly father, who suffered from macular degeneration, became the sole caregiver for his mother after she suffered a stroke. “They are fiercely independent and want to maintain their own home,” he said then. “They are not unlike families in every community across our country.”

Kempthorne’s mother, Maxine, died a year later at 87, but his father lived on.

“He said even if he lived to be 90, he’d be able to take care of himself,” Kempthorne recalled. “And he was correct. He took care of himself until he was 90, but he actually lived to be 95. And he didn’t have the resources.”

He recalled being with his father at a medical exam. Frail and in his 90s, he was told by a doctor that there were medications and procedures that could help him, but he didn’t have that coverage. “I remember saying, ‘He has the coverage: It’s called his two sons, we will take care of our father.’ I saw the tears in my dad’s eyes.”

“We were his annuity at the end,” Kempthorne said. “That motivates me. I want this industry to stand beside as many people and family members as possible.”

Ironically, Kempthorne himself depleted his retirement savings long ago, in the course of campaigning for public offices over a quarter-century.

“I did not come from any wealth,” he said. “And so, during those campaign periods, we would simply consume whatever retirement funds we had to pay for the mortgages and the food and the cars. So that’s where the retirement account went. Unfortunately, I really drained my PERSI account, all for good cause. But now I work to replenish all of that.”

That’s why Kempthorne, 65, has no immediate retirement plans. He’s held his current post as president and CEO of the American Council of Life Insurers since 2010. “I need to work,” he said. “I need to work for another five to 10 years.”

Traveling the world

He now lives in both Boise and Washington, D.C., but spends a third of his time traveling in the course of his work. Recent trips have taken him to Morocco, France, Great Britain, Luxembourg and Belgium. Later this month, he’ll go to Zurich.

In addition to heading the association that represents 94 percent of insurance assets in the United States, he’s president of the Global Federation of Insurance Associations, where he was recently re-elected to another two-year term. That’s taken him to China, Japan, Korea, South America and Africa. He’s spoken to a crowd of 1,200 in Mexico City, and just this month addressed a large, multination insurance conference in Casablanca. In the fall, he’s headed to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

His office in Washington, D.C., looks out on the Capitol dome and reflecting pond.

Kempthorne has a staff of lobbyists who do the association’s direct lobbying, but he deals frequently with the new Trump administration. When the administration asked him to make calls to senators who were on the fence about the nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the U.S. Supreme Court, he gladly called nearly a dozen of his former Senate colleagues. “Regardless of whether they were Republican or Democrat, the first thing they wanted to do was reconnect,” he said.

He also met with Trump’s National Economic Council chairman, Gary Cohn, to stress the importance of retirement savings in tax reform efforts. “I was delighted when they rolled out their views on tax reform – they said three things should be protected: The mortgage deduction, charitable giving and retirement savings,” Kempthorne said. “We need to have more opportunities and more incentives for saving. I think that message is resonating.”

Two-thirds of the life insurance business portfolio is retirement savings, he said, “so that people can be self-reliant and not totally government-reliant.” He said current data shows 50 percent of people who turn 65 will also turn 85, and half of those now in their 30s or younger will reach the age of 100.

“Longevity is here,” he said. “But just because you have quantity of life, it does not affirm quality of life.”

Political career

Looking back at his long political career, Kempthorne said the toughest job he had was governor of Idaho.

“When you’re governor, there’s no one to stand with you,” he said. “You either sign the legislation or you veto it and you say why.”

His proudest accomplishments include his “Connecting Idaho” transportation plan, which resulted in nearly 60 major highway construction projects statewide, work that recent state analyses have estimated is saving at least 88 lives a year on Idaho’s roads. “And many of those lives are students going home on holiday or vacation,” Kempthorne said.

He recalled a time when Idaho’s economy was hard-hit by the burst of the dot-com bubble, and how he spearheaded a construction project on Idaho’s college campuses that included replacing the UI’s Teaching and Learning Center. “I used to be a student in that building,” he said. “I remember it was cold, it was dark, and it was drafty. And that’s been totally corrected.”

In the face of economic adversity, he said, “I just said, ‘We’re not going to be victims of this.’ ”

He also noted his initiatives to extend fiber optic lines to rural Idaho, and to address school safety concerns in the state that helped lead to the final replacement of a deteriorated Troy High School.

“I was counseled: Do not run for mayor of Boise,” he recalled. “No one’s been successful there; the downtown will never be built, and if you ever were thinking of running for some statewide office, it’ll never happen. You’ll carry the stigma of Boise, and no one will vote for you.”

Instead, Kempthorne became the mayor who in the 1980s broke the longstanding impasse over redeveloping downtown Boise – which now is vibrant – and went on to be elected to the U.S. Senate and then governor.

Still listening

He said it all stemmed from lessons he learned at the University of Idaho, where he graduated with a political science degree and served as student body president.

“I loved the university. I loved the camaraderie of my fellow students,” he said. “I wasn’t a great student, but I did fine.”

The top lessons he learned there, he said, were, “One, be a good listener. Listen to people. And see if you could then help frame an issue that removed the rhetoric, so that you could be focused on the result. I really think I carried that with me throughout my public career – listen to people. And be tenacious, that you are there to make a difference, you are not there to be status quo.”

“I never accepted anything with the idea that I’d be a caretaker,” he said. “I was there to help make a positive difference for people.”

Kempthorne recalls campaigning for student body president as an independent – he wasn’t the candidate representing fraternities – and slipping away while waiting for his turn to speak at meetings at the various living groups or dorms to knock on doors and introduce himself, “knowing not everyone went to their meetings. And I picked up a lot of votes that way.”

He did the same when he ran for mayor of Boise, and later for senator and governor. “I still have people today say, ‘You came to my door. … You knocked on my door and you asked for my vote,’ ” he said. “It still means something to people.”

He has a vivid memory of being at his dorm the night the ballots were counted for student body president, his first election victory. “You could hear the phone ringing at the end of the hallway – a friend answered it,” he said. “Everybody was waiting to know what had happened. And the doors began opening. And I walked down this long hallway, I take the phone at the end of the hall, and I’m informed that I’ve just won the election. I turn around and look at everybody, and all my friends start clapping.”

As student president, he attended every board of regents meeting, and pressed hard to get the university to consider a student-proposed plan for renovation of the Student Union. Though the student government had hired a professional architect and consulted extensively with students to bring in their ideas, the regents were ignoring it. He spoke passionately to the regents, and they ended up adopting the student proposal. “And it was a terrific Student Union building,” Kempthorne said.

He recalled organizing students to get their input on a proposed new dome over the football stadium. That’s the Kibbie Dome today.

‘Come full circle’

Kempthorne, a California native who spent most of his early years in Spokane, originally came to the University of Idaho to study medicine. He’d worked as a hospital orderly – including at Gritman Medical Center in Moscow – and wanted to be a doctor. After discovering he “wasn’t very good with chemistry and physics,” Kempthorne switched his major to political science.

Andrew Kersten, dean of the UI’s College of Letters, Arts and Social Sciences, said, “Dirk Kempthorne provides our students with a shining example of how a University of Idaho experience, a degree in the College of Letters, Arts and Social Sciences, a positive outlook on life, and hard work can catapult a person into a rewarding life of public service.”

“I could probably take different issues I had to deal with as secretary of the interior and I could show you the thread back to experiences at the University of Idaho, or at City Hall in Boise, or at the Statehouse in Boise,” Kempthorne said. “It all adds together. And I’m still a good listener.”

He added, “To have gone to the U of I to get a medical degree, to have left there without it, but to be invited back many years later to receive my doctorate degree is very cool – I’m very flattered. … It’s kind of come full circle.”