Priscilla Wegars receives award for work with Asian-American Comparative Collection

Priscilla Wegars has made a career out of exploring and sharing the history of Asian workers and culture in the Inland Northwest.

That passion to keep digging was recently recognized when the 77-year-old Moscow resident was named one of 12 recipients of this year’s Idaho State Historical Society’s Esto Perpetua award, which translated means “let it be perpetual.”

The California native received her library degree from Berkeley before spending 1963-64 in Thailand with the Peace Corps, which is where she said she likely developed her appreciation of the Asian culture.

“You hear people say, ‘(traveling) changed my life,’ but it really did,” she said. “I had never interacted with people from other cultures. It amazed me how happy they were with so little. I realized you can live simply.”

Following the Peace Corps, Wegars moved to Moscow in 1979, a period that Wegars said some call the “Californication” period.

“I wanted to redeem myself by writing Idaho history,” she said.

She was hired into a position with the University of Idaho libraries, then became involved with university archeology projects – another one of her longtime passions – as a volunteer researcher.

“I had done some archeology before and thought Idaho might be a good chance to explore that further,” she said.

That was when Wegars got hooked exploring the sites and settlements of Chinese workers who had come to the United States, first in the 1860s and ‘70s for jobs in the mines, then during the 1880s to work on the railroads. Later on, the Japanese arrived to work primarily in the timber industry and some railways, she said.

“There are sites associated with the camps of those workers. You find broken pieces of what they left behind,” she said. “I thought it was a good idea to start collecting the whole item.”

That led to the creation of what is now called the Asian-American Comparative Collection, hosted and located on the UI campus.

Even as the primary coordinator of the collection, Wegars is a volunteer, and she said they are hoping to fund a full-time director through an endowment for the collection.

Currently, Wegars is self-employed after receiving her doctorate in history and historical archeology from the UI. The flexibility of self-employment allows her to do a range of work, from editing and proofreading to artifact analysis to speaking appearances and book writing, with plenty of time for research into personal interests.

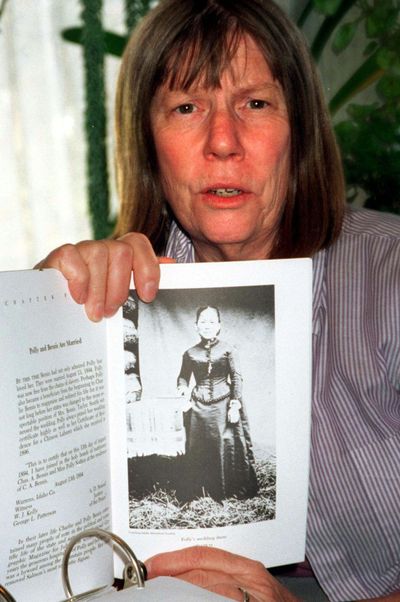

The latest topic to spark her interest is the story of a woman named Polly Bemis. She hopes to write a book dispelling the myths and misinformation about Bemis that have been passed down and published over the years.

Bemis was a Chinese woman who arrived in the U.S. in 1872, sold by her parents as a concubine for a Chinese miner in Warren, Idaho, Wegars said. Bemis later moved to a home along the Salmon River where tourist charter boats would often stop by to meet the “characters” along the river, Wegars said.

Over the years many stories have circulated about Bemis, who is sometimes referred to as the “Angel of the Salmon River.”

“So what I am trying to do is bust the myths,” Wegars said. “People cling to this idea that it was all romantic. … Her story was already dramatic enough without making stuff up.”

To do so, Wegars said she starts with reading all the information already out there in books and newspapers and she watched the movie “Thousand Pieces of Gold,” which is roughly based on myths of Bemis’ life. She then examines where the authors and writers got their information and she takes a fresh look at it.

Based on what she has already found, Wegars said she is disproving some of the stories and clearing some confusion.

“It is the detective work,” she said. “I was digging into the ground for a long time and now I’m digging in the documents. … It’s like I can’t stop. I want to put in every little tidbit I find.”

And while the digging into the past is a joy, Wegars said she hopes it allows the community to build a better understanding of Asian Americans in the West.

“It’s good for people to realize there were other races in Idaho over this long period of time,” she said.

That resonates especially true today, because, she said, “it is very distressing to see what immigrants are going through.”

Other than Native Americans, Wegars said, everyone is an immigrant, and “we have lost sight of that.”

“It is just heartbreaking to see that people are denying other people the opportunities that they themselves had,” she said.

,g000219715,g000065584

AP-WF-05-31-17 1315GMT