‘Tell’: Retired Maj. Margaret Witt tells all in new book about her legal fight

In this June 30, 2006 photo, U.S. Air Force Reservist Major Margaret Witt talks with reporters after a hearing of a case challenging her dismissal from the Air Force for being a Lesbian in U.S District Court in Tacoma. Witt retired with full benefits rather than resuming service during a announcement on May 10, 2011 at an American Civil Liberties Union news conference in Seattle. A federal judge ruled last fall that Witt’s dismissal violated her constitutional rights. The judge ordered that she be reinstated. Her lawyers and the government spent several months negotiating her reinstatement before finally reaching an agreement to let her retire. Her discharge will be erased from her records. Witt was dismissed in 2006 after serving 18 years. (JOHN FROSCHAUER / Associated Press)

Though she spent five years suing the U.S. Air Force in a highly publicized case, Maj. Margaret Witt still considers herself a private person.

Witt, a decorated flight nurse who lived in Spokane until 2014, was the force behind the lawsuit that pushed Congress and the Obama White House to repeal the military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy.

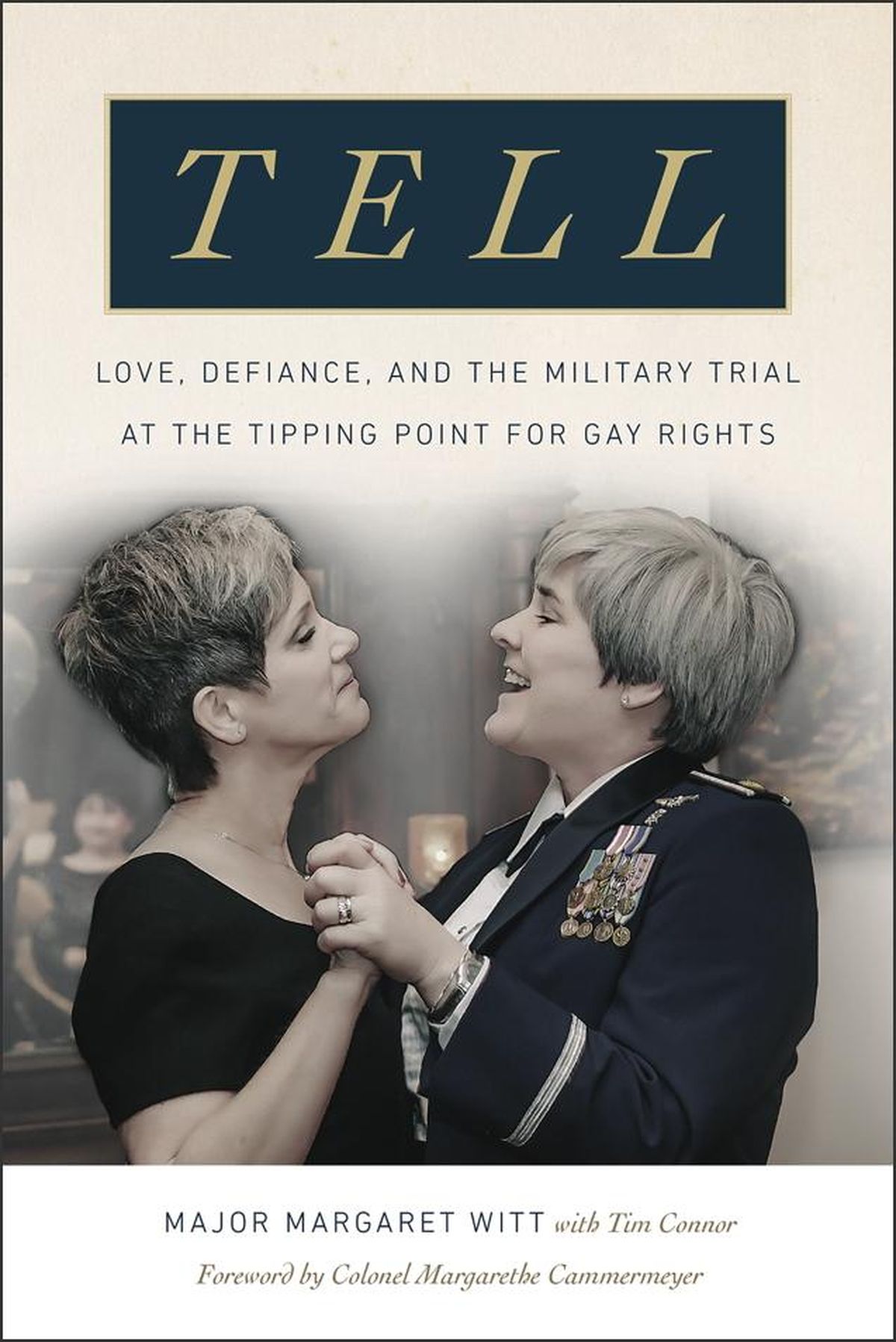

The story of her Air Force career as a closeted lesbian, and subsequent dismissal once she was outed, are the subject of “Tell,” a memoir she co-wrote with Spokane journalist Tim Connor, due to be released from University Press of New England on Tuesday.

Knowing that her story will be out in public again is an odd feeling for her.

“I almost forgot how personal it got until I saw the whole book in my hands,” she said.

She now works as a physical therapy supervisor at the Portland Veteran’s Administration and said it’s rare for her military history to come up.

“I don’t even think my boss knows I have a book coming out,” she said. “It just seems a little boisterous to bring something up like that.”

Witt and Connor will begin their press tour in Spokane, with an appearance at Auntie’s Bookstore at 7 p.m. Tuesday.

“I’m excited. I actually asked that we kick it off in Spokane,” Witt said,

Though it’s billed as a memoir, “Tell” is written in third person and reads as part biography, part legal thriller.

It opens with a narrative of Witt’s childhood and her path to serving as an Air Force flight nurse, first full-time and then as a reservist. Over the course of the early chapters, she begins to suspect and then realize she’s lesbian, and works to keep her sexuality a secret while she’s stationed at McChord Air Force Base in Tacoma.

As the book tells it, her outing came after she started dating Laurie McChesney, who was then in the process of getting divorced from her husband. He contacted McChord Air Force base and told Witt’s superior officers that she’d been in years-long lesbian relationships. Her ex-girlfriend corroborated his testimony, and the Air Force began moving to dismiss her in 2004.

The rest of the book follows her lawsuit to be reinstated into the Air Force. Connor’s reporting included interviews with federal Judge Ronald Leighton in Tacoma who first heard, then dismissed, her case.

The Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy was created because of the government’s belief that allowing gays and lesbians to serve openly threatened unit discipline and cohesion. But on appeal, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals said Witt was entitled to a trial and ruled the Air Force had to prove that dismissing Witt specifically was necessary to further a significant government interest.

That was a significant change. Essentially, the Air Force had to show Witt was a threat to unit discipline and cohesion because she was a lesbian, something they were unable to do at a subsequent trial before Leighton.

Witt said of the trial, “It was like being at my own funeral because unit member after unit member took the stand and would say all these nice things about me.” Everyone who testified for her was adamant: the only thing that had caused a problem with unit cohesion was her abrupt dismissal after years of dedicated service.

That standard of proof would be called the “Witt standard” and paved the way for Congress to repeal the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy in 2010, allowing gays and lesbians to serve openly in the military for the first time.

While Witt’s lawsuit was in progress, Connor worked at the Center for Justice and wrote about notable legal cases related to civil rights. Her case caught his attention.

“I was really appalled at the start we would even think of taking a decorated flight nurse and removing her from her peers at a time when we needed flight nurses,” he said.

Leighton’s eventual ruling in Witt’s favor following the 2010 trial also stuck with Connor.

He read the last piece of his verdict to Witt directly, saying, “Notwithstanding the victory you have attained here today for yourself and others, I would submit to you that the best thing to come out of all this tumult is still that love and support you have received from your family.”

“Judge Leighton to me spoke for the goodness of America, the basic decency of America,” Connor said. “We kind of forget now, but that was remarkable.”

As Witt’s case progressed, Connor wrote several articles about it and eventually a profile of her. In 2011, she reached out to him and asked if he would consider writing a book with her. It took a few years to get a contract, and Connor began working on it in earnest in 2014.

From the beginning, Connor said he didn’t want to write an “as told to” memoir. He thought it was important to include context, including interviews with people from her unit and narrative of behind-the-scenes politicking in the White House over the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy.

“I thought the best way to tell her story was to have the freedom to move the camera around,” he said.

The book has an extra bit of relevance following President Donald Trump’s announcement earlier this year that transgender Americans would no longer be allowed to serve openly in the Armed Forces. The book’s introduction was written before the policy reversal took place.

“It’s so unfair. It’s so wrong. And what he’s done is disrupt unit cohesion and morale,” she said of Trump’s decision. “You’re good enough yesterday but you’re not good enough today, and I know what that feels like.”

Witt will go on a small book tour, with stops in Tacoma, Gig Harbor, Kirkland and a few other Northwest cities. She planned most of them on evenings or weekends so she wouldn’t have to take time off from her full-time VA job.

She’s looking forward to being at Auntie’s.

“I thought it was only right that we kick it off there because the support that I had from my work colleagues, my friends, my neighbors. It was so amazing, and I wanted to celebrate with them on the day it kicks off,” she said.