Ballots not cast can still sway elections

Washington elections officials might be duly proud that the 2018 midterm had near-record voter turnout and more ballots cast than any other elections save the last two presidential contests.

Behind the positive news that nearly 72 percent of the voters cast some 3.1 million ballots, however, there’s a negative: Almost 30 percent didn’t vote, and more than 1 million ballots that were mailed out didn’t come back.

In Spokane County, where turnout was almost 73 percent, more than 86,000 registered voters didn’t cast their ballot.

This in a state that for years has worked to make it easier to register, by mail, online and in person. Washington arguably makes it easier to vote than any other state. Ballots are mailed three weeks before election day, and will be counted for weeks after, provided they have been postmarked by election day. Other all-mail states like Oregon require the ballots to be in hand on election night to be counted.

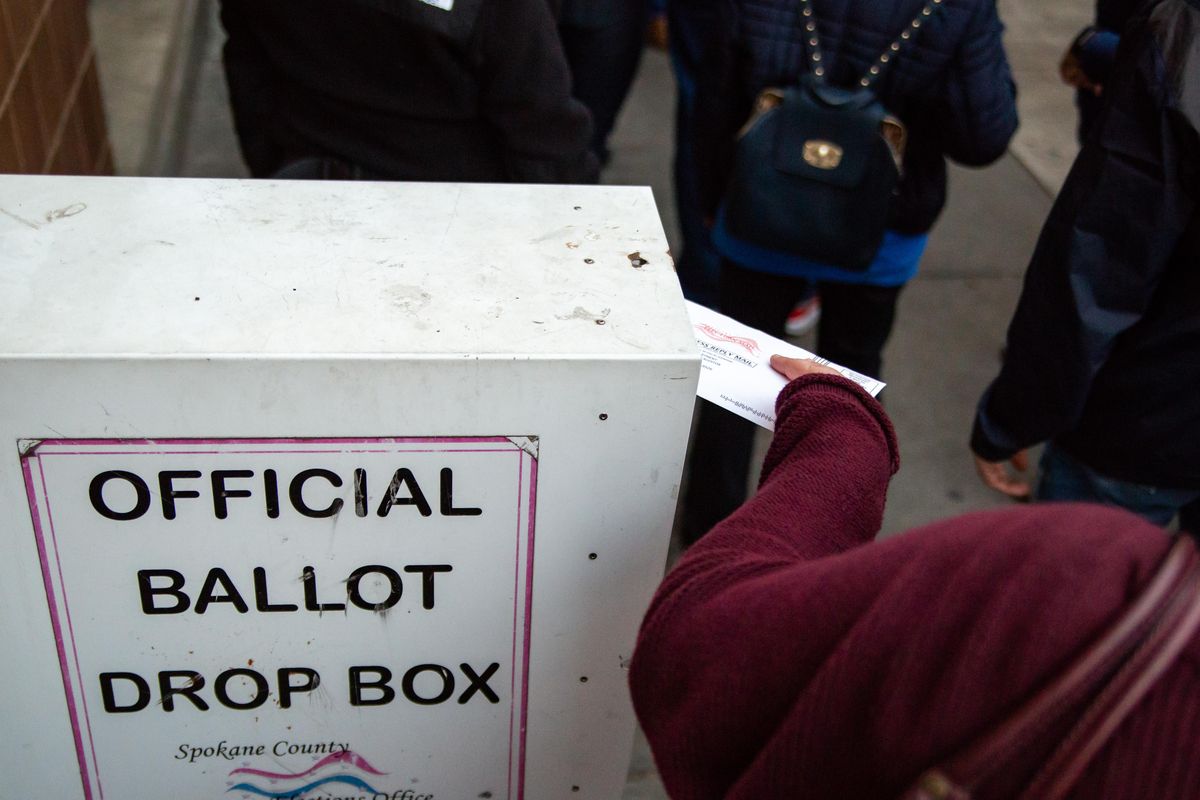

This year, Washington also covered the postage for returning ballots by mail, and required counties to install more drop boxes for voters who prefer not to mail them.

Just as voter participation varied across the county, nonparticipation by registered voters who didn’t vote wasn’t distributed evenly across the electorate. A computer analysis by The Spokesman-Review of Spokane County’s final vote totals shows they varied widely, with some precincts having only dozens of ballots that weren’t cast and others where hundreds never left the voter’s home.

That analysis reveals a major hurdle for any Democrat seeking to capture Eastern Washington’s 5th Congressional District seat, which has been held by Republicans for a quarter century. Spokane County is by far the most populous, and while a Republican can find enough votes in the surrounding counties to lose Spokane County by a small margin but still win the election, a Democrat probably can’t.

Democratic challenger Lisa Brown won many precincts where nonparticipation was high, with 300 or more voters not sending back their ballots. As expected, she beat Republican incumbent Cathy McMorris Rodgers in the 3rd Legislative District, a historic Democratic stronghold. But the 3rd has about 20,000 fewer registered voters than the other two Spokane County-based districts. Turnout was about 5 percentage points lower than the county average and nearly 25,500 ballots that were mailed to registered voters in the 3rd District weren’t sent back.

Some of the highest nonparticipation was in Spokane city precincts north of Interstate 90 between North Division Street and the city limits. West Central, East Central and the growing community at Kendall Yards also had high levels of nonparticipation compared with precincts outside the city.

McMorris Rodgers also carried some light voting precincts – including Fairchild Air Force Base, which has 792 registered voters but returned only 193 ballots – but did particularly well in rural areas where participation was high and she topped Brown by 200 or more votes.

Although the 86,000 uncast Spokane County ballots are greater than McMorris Rodgers’ margin of victory in the entire district, there’s no way to predict how nonparticipating voters would have marked their ballots. Rather, it shows a significant number of voters who didn’t take the time or have the interest to cast a ballot in this election.

A computer analysis by the newspaper of the last presidential election shows the pattern of nonparticipation didn’t change significantly for the midterm, even though turnout was about 10 percentage points higher in 2016.

That pattern of uncast votes points out a problem for Democrats, not just for congressional races but also for countywide elections where the GOP has dominated for the last decade.

Democrats may be courting the types of voters who are least likely to cast ballots, said Cornell Clayton, who teaches government and politics at Washington State University, where he serves as director of the Thomas S. Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service.

“It’s typical that Democratic voters don’t turn out at the same level as Republicans, especially in midterms,” Clayton said.

Democrats tend to make their appeals to younger voters and lower-income voters, both of whom may be more mobile than average, he said. While the turnout for younger voters might have been up this election, it was probably well below that of older voters, who tend to back Republicans in recent years.

The computer analysis suggests that was likely this year, as precincts around the Gonzaga University campus in Spokane and Eastern Washington University in Cheney were among those with high levels of nonparticipation, despite candidates’ efforts to register young voters in the months before the election.

Record amounts of money were spent on the congressional race and on some initiative campaigns, flooding the airwaves for the weeks after ballots had been mailed out.

But nonparticipating voters clearly need more than campaign ads to get involved, Clayton said. To convince them cast their ballots, candidates need to go out into those neighborhoods and do more “grassroots, get out-the-vote activity,” he said.

They need to knock on more doors, go to more community forums and talk to more Chamber of Commerce, Kiwanis and Rotary luncheons, Clayton said. Candidates also need to talk to some groups outside their comfort zones because some nonparticipating voters are likely persuadable.

For Democrats, that might be church groups for conservative denominations like Catholics and Mormons, who frequently vote Republican but might not approve of President Donald Trump, he said.

Republicans could follow similar grassroots campaign strategies for collecting more votes in traditional Democratic precincts where voter registration is strong but participation low. Based on recent election results, however, their need to change what they are doing isn’t as great.