Outdoor writing contest: My Native Land

Walking with my ancestors on Native peoples’ land and the lives they lived. These waters have seen rivers run the memories of my people. The wind and the birds tell the stories of my ancestors. My family and I keep the traditions passed down from my dad’s grandma and from her grandma. We are taught to love and care for the land, the sacred water, and all the land gives us.

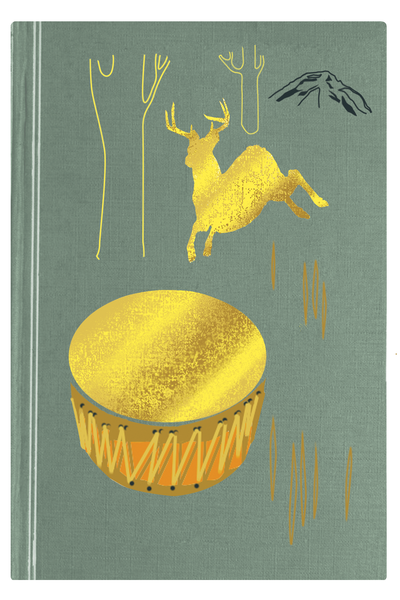

My family powwows all year long. We travel all across America. From the plains of Montana to the islands of Hawaii. Native Americans gather everywhere and anywhere. We sing and dance with one another. This is of my favorite parts about being Native American. I love the feeling of ground below my feet as I dance, the dirt that has been flattened by many years of powwows. The sound of the music, the drums, and the men and women singing in harmony. You can feel every pound of the drum go through your whole body. All around the sounds of the bells and jingles from people moving. Dancing with my friend and walking around looking at all the beautiful bead work. Camping at the powwow, tents and teepees right next to each other. We camp at the same spot every year surrounded by friends and family. That’s where my friends and I run through and play games. My children will camp in these places that all my friends and I grew up.

Our family gathers native foods and medicines all summer and fall long. The end of spring brings us huckleberries. Walking up miles into the mountains to find a big patch of berries, I feel the presence of women picking huckleberries with me, the women that have picked in this place generations before me. We bring back buckets full of gallons of huckleberries. We divide them up depending on what we plan to do with them. My mom makes wojapi, a Northern Cheyenne soup made only with huckleberries and honey, almost the same as pudding. My grandma and I go and lay out the berries to dry. My dad and brothers pack them up so we give them to the rest of the family and anyone who can’t make it out to pick. When everything is done we put it away for winter and start over the next year.

In midsummer the camas root is ready to be plucked from the ground. The whole family, including babies, adults, and the grandparents, all come together. The dirt is soft and you can almost pull the camas out of the ground. My dad says the deeper the camas, the bigger the bulb. It’s that way because you must work harder. The umbrella-like plant covers every inch of the ground. Once you get the root, you place the top of the flower underground so there will be more for the next year. We dig the root out with metal bars shaped like a letter “t.” Every family has a spot they like to come to every year. We dig on a little piece of land right off the highway. Years ago, the land was filled with camas for miles. Slowly, our land we’ve been digging for years has been swallowed by the new world.

In the beginning of fall, we dig for water potatoes or wapatos in my native tongue. We go out to the edge of the lakes; the water lowers this time of year and leaves the land in mud. You walk out as far as you can. Feeling around in the mud with your toes for a bulb-shaped plant that feels like a rock. The mud is deep and cold, it can go up to your waist. Every step you take sucks you deeper into the mud. You pat down the tule reeds to have a place to get out of the cold mud. It’s like a life raft on a sea of mud.

The earth is what helps me stay connected to my ancestors. There is only one world. I am taught that we have to care for it as much as it cares for us. I’ve grown up to learn everything that earth has to give, and I will pass it down to my children. My children will pass it down to theirs, and it will continue like that for generations. I will love and care for this land, because this land makes me who I am.