Some regret loss, others see trend as midcentury homes give way to new construction

On Dec. 11, a 2,000-square-foot home fronting Manito Golf and Country Club was sold for $600,000.

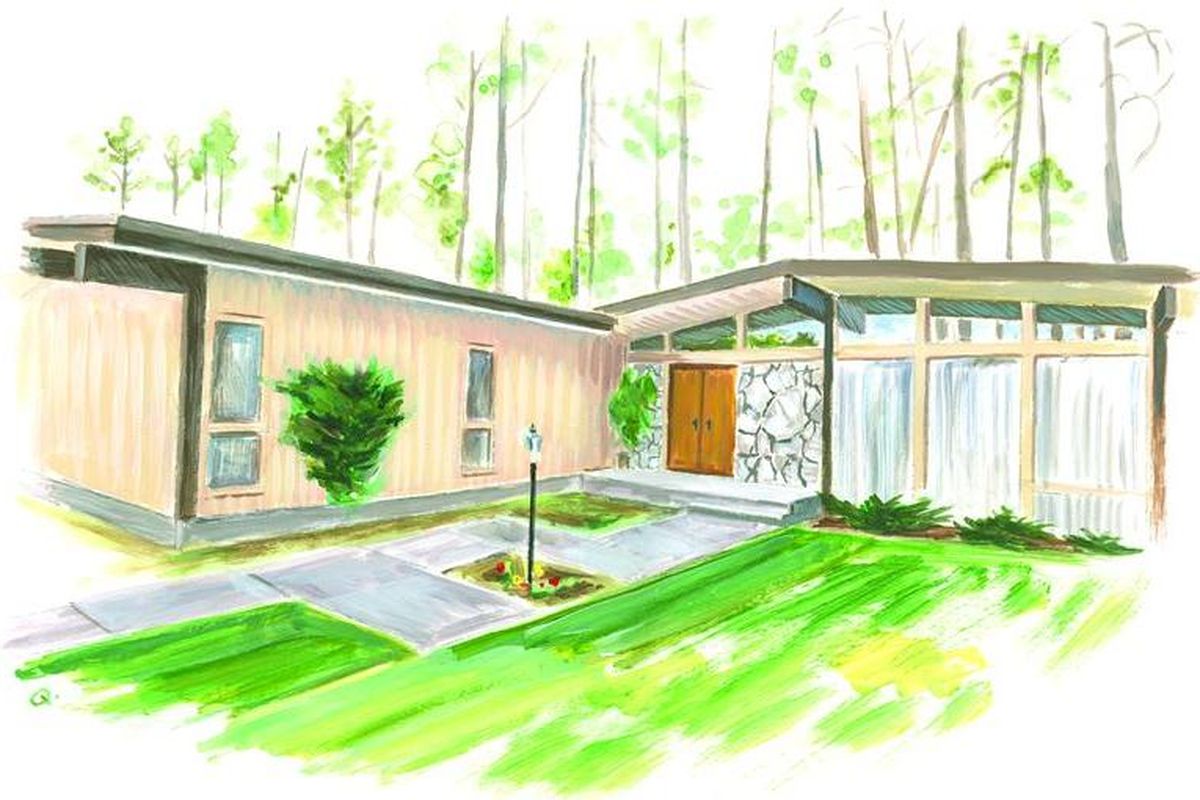

The home, an example of midcentury modern architecture built in 1965, was designed by architect Ron Sims for J. Birney Blair, a prominent television adman who would soon become the president and general manager of KHQ.

When he designed the home, Sims was still a young architect working for McClure & Adkison, the company responsible for some of the finest buildings in the middle of the 20th century in Spokane. Prior to his work on the Blair home, Sims had participated in the design of the brand-new Ferris High School, and would go on to build the Spokane Veterans Memorial Arena and Shriners Hospital at the base of the South Hill.

Blair lived in the house until his death in 2014, and his wife, Marcy, stayed there until last year, when she moved to the coast and put the home up for sale.

Less than a month after she sold it, the city issued a demolition permit to the new owners and the 52-year-old house was gone. Three months later, on April 9, the city issued another permit, for a brand new 5,300-square-foot, three-bedroom home. A blank foundation holds the spot now.

It’s not the first time a notable home fronting the Manito golf course was destroyed to make way for a new home, and many say it won’t be the last. In the past 16 months, four homes facing the private South Hill club have been removed to make way for newer, bigger houses.

Besides the Blair home, the historic John G.F. Hieber house was purchased in 2012 for $819,000 and demolished last month to make way for a new home. On Perry, two homes were gone not long after their buyers paid well above the median home price in Spokane – one was bought in June 2016 for $415,000 and the other in October 2016 for $375,000.

Pam Novell, a real estate agent and managing broker at Windermere Manito, said demolishing existing homes to build new ones is not something that would have happened in Spokane a decade ago, and chalked it up to changing trends in how people want to live their lives.

“Ten years ago, people wanted 7,000-square-foot homes on acreage. They don’t want to be on acreage anymore. Their life is so busy,” Novell said. “They’re going all the time, so they don’t want to have a 10- or 15-minute commute from their acreage.”

Novell said she’s watched as homes priced below $300,000 have gained quickly in value, and recently saw a house on Upper Terrace Road purchased for $2 million in cash.

“I don’t think you would’ve seen this 10 years ago,” she said, noting that the area around the Manito club is one of the prime real estate areas in town, with its proximity to the city center and the spacious, bucolic lots fronting the course. Still, she said, it was extraordinary to see what was happening there.

“That area is one of the few streets where we’ve seen that done,” she said. “I can’t think of any other street on the South Hill where this is being done.”

‘We’re going to see it happen more’

Mike Redmond is big league.

A graduate of Gonzaga Prep and Gonzaga University, the catcher spent 13 seasons in Major League Baseball and was a member of the World Series-champion Florida Marlins in 2003. After also playing for the Minnesota Twins and Cleveland Indians, Redmond went on to manage the Marlins and coach for the Colorado Rockies.

But he knew he wanted to settle in Spokane, and he knew wanted to live on the Manito golf course, where he’s a member.

“We love the neighborhood. We have friends in the area,” he said. “When we looked at places where we wanted to move, that was very high on our list. Then that house became available.”

That house was the Blair home, and Redmond said he and his wife, Michelle, considered renovating the home, but the numbers didn’t pan out.

“We looked at every option and that option was the best for us,” he said of demolition. “The cost of remodeling, it just made sense to start fresh. We understand the neighborhood, and we wanted to make sure we did our best effort.”

Though he’s hired an architect with HDG Architecture to design a home “that would fit not only what we wanted but would fit in the neighborhood and fit into the surrounding area,” he said he’s aware the decision to demolish probably didn’t sit well with some of his new neighbors.

“You realize when you do something like this not everyone is going to be happy. We’re cognizant of that,” he said. “But we’re replacing the house we tore down with something appropriate. At the same time, we’re looking forward to making our own history in that house on that lot and in that neighborhood.”

Redmond predicted he wouldn’t be the last to demolish and replace an old home there.

“There’s only a few houses on that golf course,” he said. “This probably isn’t the last time this happens.”

Rob Higgins, executive officer of the Spokane Association of Realtors, said the act of buying a home in Spokane only to tear it down isn’t a trend. Yet.

“It’s not totally new, but we’re going to see it happen more. It’s all about location,” he said. “I remember hearing about this happening in Seattle a number of years ago. Right now, where you see it happening in Spokane is on a golf course, or on the river.”

Higgins, like Novell, said it came down to how people choose to live their lives.

“Traffic is getting to be more of a problem,” he said, noting people want to live closer to town to avoid congestion on the roadways. He counted himself among them. “Personally, I live in the city and don’t deal with the freeway. By choice.”

Spokane’s midcentury legacy

The right to acquire, use and dispose of property freely is part of Americans’ freedom of choice.

Ann Price, president of Spokane Preservation Advocates, recognizes this, but suggests things are a bit more complicated.

“There’s a limitation on what preservation groups can do,” she said. “Our hope is to educate those homeowners and realtors better about the value of maintaining those homes and the history they represent.”

In the case of what’s become known as midcentury modern architecture – a style that is defined by its break from a highly ornate past, clean simplicity and, at times, flamboyance – Price said the homes and buildings scattered around the city are unique to Spokane.

“Midcentury modern is so important here in Spokane because we had such a great group of active architects,” she said. “We are losing that era when those homes come down.”

The class of architects Price refers to includes Royal McClure, Bill Trogdon, Thomas Adkison, Bruce Walker, Ken Brooks and Warren Heylman. Some examples of their work are the Washington Water Power Central Service Facility, which houses the Avista headquarters; Parkade parking garage; Shadle Park water tower; Cooper-George Apartments; and many homes.

As these buildings reach and surpass 50 years in age, they qualify for historic preservation, but many people still struggle to see the beauty in the buildings. According to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, midcentury buildings are “among the most underappreciated and vulnerable aspects of our nation’s heritage.”

Price said she thinks that’s changing.

“Part of it is just a change in taste, as time goes by,” she said. “We are seeing a turn in that trend. The whole midcentury modern style is attractive to a younger group. They like the simpler style.”

But in the end, Price said, “not every home is preservable” and any chance to save them “really has to happen on the neighborhood level.”

Logan Camporeale, the historic preservation specialist with the city and county, agreed with Price.

“We would advocate for those buildings to have some sort of protections, but we just don’t have the tools to protect those buildings. There really isn’t much we can do,” he said. “I’m sure there are other homes that are targeted, but it’s going to take some sort of frustration from the neighbors to get something done.”

Diversity of architecture

Ben and Kelly Drew Folger aren’t from Spokane, but after getting their undergraduate and graduate degrees from Gonzaga University, they decided to make it their home.

With her law degree and his master’s degree in business administration, the two have done well, and chose the South Hill to settle down.

“During those college years, we both fell in love with Spokane,” Kelly Drew Folger wrote in an email. “After living in another area in town for a few years, we chose to relocate to the South Hill. We were drawn to the Manito area because of the exceptional schools, the wonderful, neighborly community, and the proximity to many conveniences, like parks, grocery stores and downtown.”

They bought a home built in 1965 on Perry for $415,000 in June 2016, and she said they originally planned to renovate the home, and sought an architect to design the remodel. Bids came back “unexpectedly expensive,” and the Folgers decided a new home was in order.

But the home they removed was not demolished.

“Personally knowing the prior owner and some of the history of the house, we decided that instead of demolishing it, we would move it,” she wrote. “So, we found a moving company that relocated the home to another lot in Spokane. Our hope was that others could live in and enjoy the home we purchased.” The home now sits on East Broadway Avenue in Spokane Valley.

Not far from the Folgers, Emily Williams and Matt Beard bought a house built in 1971 for $375,000 in October 2016.

Williams, a plastic surgeon, said it was never their intent to raze a house in favor of a dream home. Instead, they wanted to get closer to town – with its restaurants, parks and their friends – while still being near the outdoors.

“We used to live outside of town and we really enjoyed the closeness of nature,” she said. “We wanted to move closer to the city. We really wanted to be close to the bluff trails.”

They were “very open minded” when they began the house search, which led them to the home on South Perry.

“The thing we didn’t expect to do was what we ended up doing,” Williams said.

The ’70s home was “not really salvageable” from years of being lived in without much upkeep, Williams said. The basement was so low “my husband couldn’t get in there without ducking.”

So they demolished it.

“That’s the way things work out,” she said.

The couple hired Mike Christensen, an architect with Form Architecture, to design a new home, and they moved in recently. Williams said she hopes the house contributes to the “diversity of architecture” in Spokane.

“I can understand people being distressed when they see things changing. Hopefully in the long term the changes being made are positive,” she said. “I love the fact that Spokane has such diverse architecture. … There’s a lot of variance, from one house to the next.”

No stance from Comstock

John Schram, co-chair of the Comstock Neighborhood Council, lives on High Drive, not far from the Manito club.

“I live in a beautiful midcentury home,” he said. “We purposefully bought it and moved into it.”

Though he said he was confused by people who bought homes they didn’t want, or property with pine trees when they “don’t like raking needles,” he was careful to note the neighborhood council represents everyone who lives in Comstock, and has no official stance on home preservation.

“The question is always, how aware are people prior to the bulldozers coming in? Of course, everybody’s aware after the fact,” said Schram, a financial planner who owns a retirement investment company. He added that he would prefer better notification to residents about nearby projects done with plenty of time for people to lodge comments.

“If it were my preference, there would be a longer life cycle to that,” he said, adding that residents concerned about preserving homes in their neighborhood should attend neighborhood council meetings.

“We’re conduits to the different agencies in the city and we’re a good place to start that conversation,” he said.

Stay or go?

Sims graduated from Washington State University in 1959 with a degree in architecture. His first job was working for Heylman, the architect behind the Parkade, Spokane Regional Health Building and the public library in Colfax.

In 1961, he was hired at McClure & Adkison. Nine years later, he started the process to become a partner at the firm, and soon the company was renamed Adkison Leigh Sims Cuppage Architects. Though Sims retired in 2000, the company lives on and is now called ALSC Architects.

Sims worked closely with the Blairs when designing their home on South Perry Street in the mid-1960s.

“It was just a simple rancher, one-story home with a basement, that took advantage of the property and views of the golf course. Pretty simple plan, nothing that complicated,” he said. “A well-planned and well-organized home that worked well for them.”

Though Sims said the house was “probably in need of an update,” he lamented its loss.

“I’m not surprised, but it’s unfortunate that it happened. Some things you have no control over,” he said. “Whoever bought it thought it was better to start from scratch.”

Sims said he was more upset about the demolition of the Hieber house on 54th, just around the corner.

“It was a real disappointment to see John’s residence demolished up there,” he said. “That was really a fine project that Warren designed.”

Sims is proud of his work as an architect, and said he had “just a wonderful career over a long period of time.” His work includes the Hillyard branch of the Spokane Public Library, and the renovation of the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library that reoriented and created a new central mall at Eastern Washington University, not to mention his work creating the Shriners Hospital and the Arena.

Sims also was heavily involved in the work to remake the city center in preparation for Expo ’74, transforming the industrial yards that dominated the city core into what is today Riverfront Park. Though he doesn’t mention Sims, J. William T. Youngs does praise Sims’ boss, Adkison, in his book, “The Fair and the Falls,” calling him “one of the essential figures in the fair.”

Sims said he worked closely with Adkison during this time and participated in the decision to demolish Union Station, an old train station that dominated a block of Spokane Falls Boulevard between Washington and Stevens streets.

He doesn’t regret the determination not to save that building.

“Each building needs to stand on its own merit. If it deserves to be preserved, then it should it be,” he said. “The Union Station downtown became a very much debated project: should it stay or should it go?”

As the world’s fair approached, some advocated to save the old station for its classic architecture and historic significance. Ideas were floated about repurposing it as a museum or park building. In his book, “Spokane Building Blocks,” Robert Hyslop wrote that “the desire for newness overcame the appreciation of durability.”

Sims disagreed.

“That was a good thing. There was no long-term purpose that could be defined,” he said. “It had to go. It really did.”