Book review: Hanford is horrific for Millie in ‘The Cassandra’

An acquaintance who studied electrical engineering received a plum job offer from a military contractor after graduation. He turned the offer down. Unlike poor Mildred “Millie” Groves in this novel, he could not see an ethical way to dispense his labor for blood money.

Millie in “The Cassandra,” graduate of an Omak, Washington, secretarial school class of five, gets a job on the Hanford Project during World War II. Plutonium is being manufactured there for the bombs to be rained on Japan. Millie’s ability to foresee the future taints her being. Taints it because, like the prophetess of the book’s title, she is fated never to be respected or believed.

Disturbing visions stupefy her. Sleepwalking along the Columbia River, she sees stones transformed into skulls. She sees an irradiated “woman with her breast blackened and burned, pockets of flesh half-melted.” Millie awakens with sand in her mouth, feet cut and bruised. In a scene as disturbing as it is unforgettable, she stuffs herself a fistful of desert dirt.

The men at the Hanford site demean her, poke fingers in her fleshy middle, ridicule her innocence. As a seer, though, Cassandra declines to fall in line. She knows the high price of capitulation. Millie recalls Toni Morrison’s damaged Pecola in “The Bluest Eye” (1970), Ira Levin’s “The Stepford Wives” (1972) and Margaret Atwood’s women in “The Handmaid’s Tale” (1985).

Character and conflict enrich good fiction, and “The Cassandra” offers both aplenty. Millie’s naïve hopes for marital bliss plague her. Frightening prognostications trouble her nights. Strong, ignorant men entice and disgust her. As she wanders outdoors breathing wind-blown alkali, the “dark sky deepened and thickened, souped with stars” (90).

The book’s characters are remarkable. Sweet Beth who safeguards Millie but falls for the wolfish Gordon. Kind but homely Tom Cat, who loves Millie but whom she shoves into the Columbia River. Sister Martha, wicked and abusive, harking back to Cinderella. Their mother, a bitter hypochondriac who changes just enough to save her damaged daughter in the end.

Round characters in novels undergo alteration, and her mother’s growth contrasts with Millie’s deterioration. Brutalized by twisted visions, belittled by warmongering males at the Hanford site, Millie comes to be crazed, degraded, isolated. Her fate is one shared by certain climate-change activists and Hanford downwinders whom the federal government has ignored.

Author Sharma Shields has a stake in all that mess. Like many others in this region who are afflicted by multiple sclerosis, her physical trials must share some premonitions with the Greek soothsayer Cassandra. Shields, though, unlike her crippled protagonist in this book, enjoys a rich and productive life as a Spokane writer and mother.

Millie’s unreliability as a narrator ventriloquizes her author at times. Breaking character, undereducated Millie editorializes on the carelessness of ancestral fathers who “misshaped and bullied” their homeland – a land her “parents and peers continued to bludgeon and disrespect” in their own generation. She speaks in polysyllabic words such as “quotidian.”

“The Cassandra” joins the growing list of environmentally inflected novels in our belated age. Climate change alone is changing up our literature, inspiring words like “snowbirds” for people who fly away to escape the annual smoke from wildfires, “cli-fi” for climate fiction and “Anthropocene” for the current geological epoch named after our species’ calamitous impacts.

This novel also joins those nonfiction books on Hanford – accounts such as “Atomic Harvest” (1993), Atomic Farmgirl (2000), “Atomic Frontier Days” (2011) and “Plutopia” (2013). As fiction drenched in cataclysm, though, “The Cassandra” opens pores to a collective unconscious.

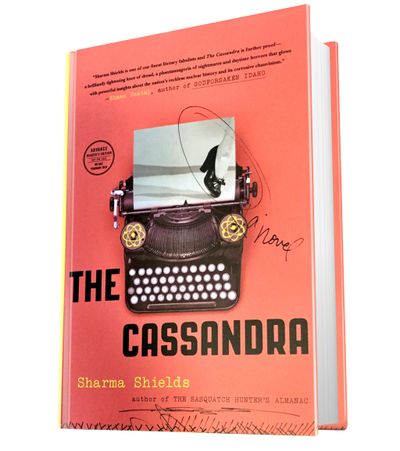

History buffs will enjoy this novel’s layers of language from 75 years ago. Millie yearns for shoes like Dorothy’s in “The Wizard of Oz,” one of which illustrates the book’s slipcover alongside a manual typewriter. Poor Millie’s job is to clack away on that manual beneath the gaze of a male Dr. Hall intent on developing the Hanford “product” that will change WWII.

Paul Lindholdt is a professor of English at Eastern Washington University and an author most recently of the book “Making Landfall.”