Washington State luminaries John Chaplin, Phil Hinrichs: Time to honor Coug legends John Olerud, Henry Rono with statues

In 2016, to commemorate its first 100 years, the Pacific-12 Conference named athletes of the century in all its sports.

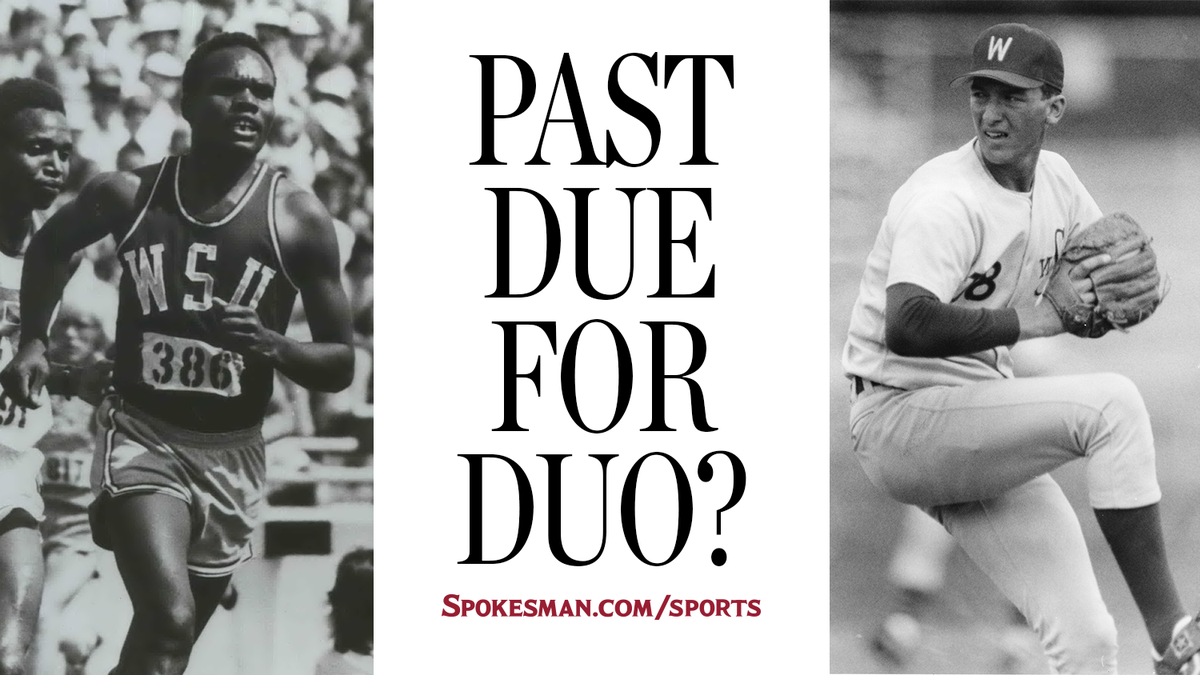

Washington State was the king of spring. John Olerud, who played three superior seasons for the Cougars from 1987-89, compiling a career batting average of .434 and a 26-4 pitching record before going directly to the major leagues and playing in the World Series for the Toronto Blue Jays as a rookie, was named the Pac-12 baseball player of the century.

Henry Rono, who set world records at four distances in 81 days in 1978, and between 1976-80 won the NCAA cross country championship three times, the steeplechase twice, set NCAA meet records in both the 5,000 and steeplechase the same day, and won an NCAA indoor 3,000 championship, was the track and field athlete of the century.

While their awards were heralded at the time, “it was probably a two-paragraph press release,” grumbled former WSU track and cross country coach John Chaplin, 83, master of under- or overstatement, as the case requires.

Old Cougar hands like Chaplin, who led the Cougs from 1973-94, won the 1977 NCAA Indoor National Championship, four conference cross country and track championships and compiled a 202-15 dual meet record, and Olerud’s late coach Chuck “Bobo” Brayton, 1,162-523-8 in games from 1962-94, who took WSU to the College World Series in 1965 and 1976 and won 21 conference titles, including 11 in a row, were accustomed to thriving in the Pac-12. They finessed modest budgets, worked smarter to seize opportunity whenever it presented itself and employed every advantage in their canny ways.

To them, the athlete of the century honors not only celebrated deserving competitors but must also have validated an era when coaches like Brayton and Chaplin routinely turned lead into gold.

A mere tip of the cap to Rono and Olerud was not the sort of thing Chaplin was likely to let go.

Things may simmer at length for Chaplin, but they seldom are entirely extinguished. While watching a Notre Dame football game this fall, when broadcasters speculated whether the university would erect a statue to coach Brian Kelly if he passed Lou Holtz and Knute Rockne for most wins in program history, Chaplin was reminded of Rono’s Pac-12 honor.

Rono deserved a statue on campus, his old coach decided. With a bit more digging, Chaplin found Olerud had similarly been proclaimed athlete of the century and figured Olerud merited being celebrated in bronze, too.

Since he remains as well connected at WSU as anyone, Chaplin contacted Phil Hinrichs, 63, an old Cougar luminary in his own right.

After graduating from Pullman High and putting in two years at Yakima Valley College that earned him a spot in its hall of fame, Hinrichs pitched two years for Brayton at WSU then embarked on a five-year career as a minor league relief pitcher between 1979-83, reaching Triple-A. He returned to the Palouse and is president and CEO of the family’s five-generation business in chickpea production, Hinrichs Trading Company, and he is an enthusiastic supporter of WSU athletics. It took no great effort for Chaplin to enlist Hinrichs in a statue quest.

“It was probably the last time people simply decided they were not missing Cougar baseball games. They were listening to them on the radio. It was dialed in,” Hinrichs said, recalling Olerud’s era.

“Nobody could fill that stadium like him.”

Hinrichs helped Brayton coach an Alaska Summer League team on which Olerud played, and Brayton told Hinrichs to check out his left-handed pitcher. Hinrichs came back marveling at Olerud’s deadly accurate slider, his economy of motion.

“I told you to check him out, not change him,” Brayton said. “The kid’s a natural.”

At the plate, Olerud could effortlessly foul off pitches until an exasperated pitcher would finally lose focus and give up an offering Olerud could drive, frequently for extra bases, with a stroke reminiscent of Ted Williams.

While WSU fans were fortunate to have ample opportunities to watch Olerud play in Pullman, Rono’s greatest feats, by contrast, mostly reached the Palouse in reports from around the world. During his incomparable 1978, he set the 5,000-meter world record in Berkeley, California, the steeplechase record in Seattle, the 10,000 mark in Vienna and the 3,000 in Oslo, Norway.

Never one to pass up a chance to jab a finger in Oregon’s eye, Chaplin famously slowed down Rono during a steeplechase in Eugene, because he didn’t want him to set the record there. Recalling the event now, Chaplin said a meet official and friend told him the Oregon steeplechase pit was too shallow, and a record wouldn’t have counted. At the time, Chaplin, simmering after a sportswriter asked him if Rono could read or write, told the Oregon writer, in no uncertain terms, that Oregon fans didn’t deserve a world record.

“And besides, we were going to set it in Washington,” Chaplin said.

Four decades later, his bravado still makes him snicker.

“Probably the dumbest thing I ever did,” Chaplin said.

But Rono made good on the claim. On May 13, a week after the Oregon meet, Rono ran 8 minutes, 5.4 seconds at the University of Washington, a steeplechase world record that stood for 11 years.

John Ngeno, Chaplin’s first great Kenyan runner at WSU, pointed him to Rono. Chaplin said he knew what he had in Rono early in his freshman year when the Cougars were training in a Snake River canyon.

Samson Kimombwa, a teammate, had set the 10,000 world record in 1977. In the canyon, however, “Rono made him look like a high school kid,” Chaplin said.

Factors such as other competitors, the weather and fate may influence a runner, but in Rono’s case, his talent was matched by will.

“You could tell him what to run, and he would do exactly what you told him,” Chaplin said. “He would not argue. He would just do it.”

Chaplin’s and Hinrichs’ quest to honor Olerud and Rono is coming to the attention of WSU Director of Athletics Pat Chun. In the midst of a pandemic and an ongoing financial crisis, the day-to-day running of the athletics department takes precedence over fundraising for statues, Chun said.

Also, there is no procedure to which Chun can refer to determine who gets a statue and where on campus.

“This has nothing to do with the merits of both athletes,” Chun said.

“This is an institution and an athletic department that takes pride in its history.

“It’s a wonderful thought by coach Chaplin, and this is a conversation we are willing to have, perhaps five or 10 years down the road.”

Such an answer, of course, is less likely to appease old Cougs like Chaplin and Brayton’s former player Hinrichs than it is to engage them.

And those guys have a long history of rising to a challenge, as Rono’s and Olerud’s presence in Pullman attests.