Nine things parents should consider when searching for anti-racist media for their kids

I am a person of color and a mother who regularly talks to my two elementary-age kids about all sorts of topics, including adoption, gender dynamics, LGBTQ issues, immigration, politics and religion. I’m trying to raise critical thinkers who are compassionate about the challenges that other people face and comfortable talking to me about things they see, hear and feel.

As current events push the reality of racial inequities to the forefront of many discussions, it is apparent that many white parents need and want more resources and guidance on raising children who are kind, caring and empathetic when it comes to race. Plenty of articles have been circulating with recommendations for books to start with, but it’s also important for parents to know how to find and vet media for their families.

Over the years, I have developed guidelines that I use to expand my family’s anti-racism library. Here are some ways to find books and other media that will help you raise children who are culturally aware and anti-racist:

Research media as if you were a black and indigenous person or person of color looking to educate their BIPOC (black, indigenous, people of color) child. Don’t simply search for books on how to talk to kids about race; that will probably lead you to white authors whose perspective might include significant unconscious bias. Those books do have value, and they are certainly better than nothing, but to empathize and understand anyone’s experience, it’s good to have firsthand accounts and stories.

Look for books about BIPOC communities written by BIPOC authors. Examples of popular Black authors include Jacqueline Woodson and Vashti Harrison for younger readers and Christopher Paul Curtis and Rita Williams-Garcia for older readers. Books with specific award designations, such as the Coretta Scott King or Belpre Medal, are a good place to start if you are in a hurry. Check out Lee and Low Books, the largest independent multicultural children’s book publisher in the country, for high-quality resources. This is not to exclude books written by white authors but to amplify the voices of BIPOC authors and bring awareness about whose perspective you are reading.

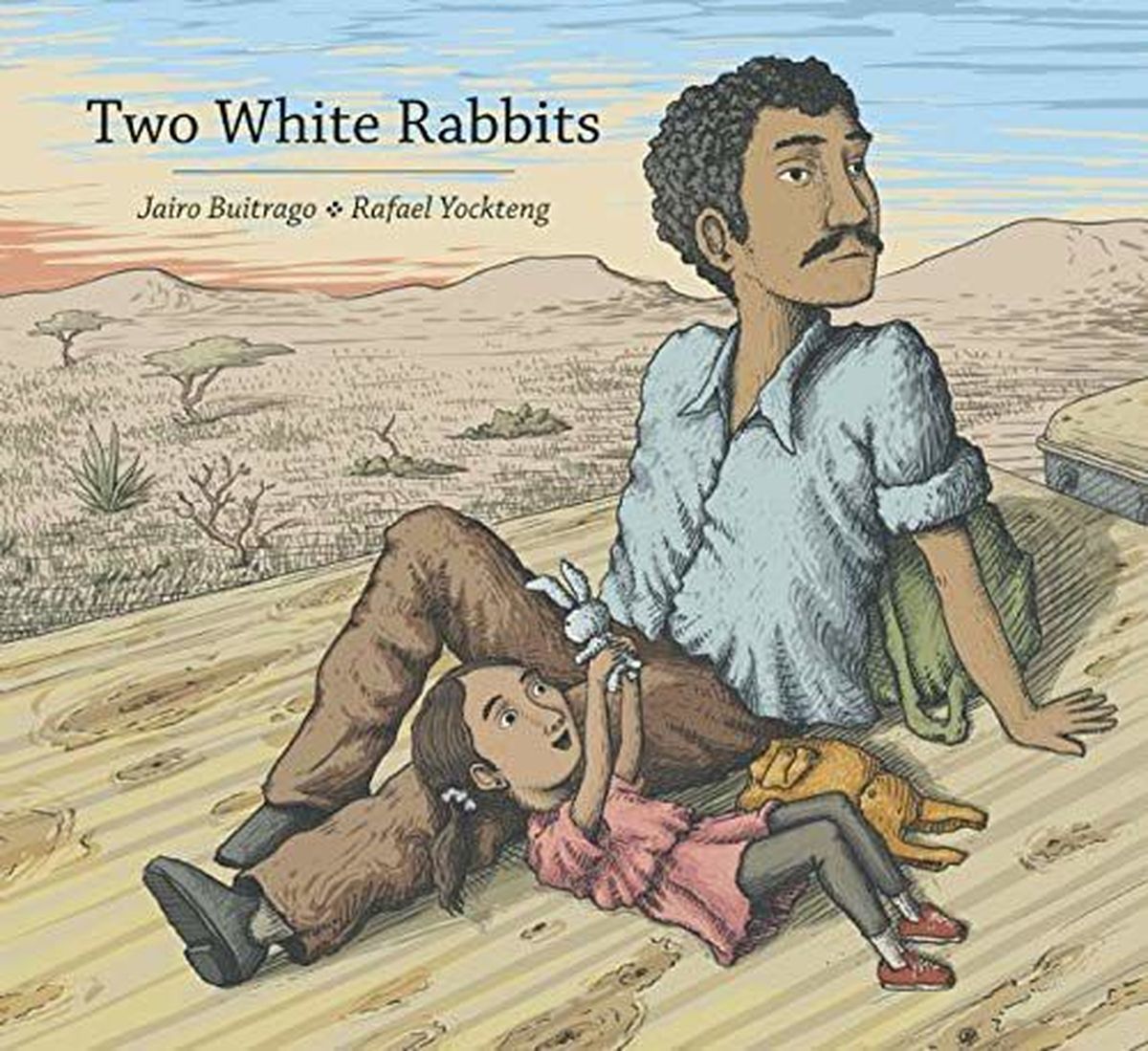

Get books from the “New Releases” sections of bookstores and libraries. Newer books will be more likely to have BIPOC protagonists and to address complex subjects such as immigration, discrimination, nontraditional families, income disparity, bullying and segregation. If I am in a hurry, I grab a few books from that section. Some of my favorite finds have included “Double Trouble for Anna Hibiscus” by Atinuke; “New Shoes” by Susan Lynn Meyer; “Two White Rabbits” by Jairo Buitrago; “Carmela Full of Wishes” by Matt de la Peña; “Hair Love” by Matthew A. Cherry; “Mommy’s Khimar” by Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow; “Dragon Pearl” by Yun Ha Lee; “As Brave As You” by Jason Reynolds; and “Snapdragon” by Kat Leyh.

Read the one-star reviews. Book reviewers often have excellent points for why they don’t like a particular book. A negative review doesn’t mean a book is bad or unreadable, but it does mean there could be underlying stereotypes or generalizations that will need to be addressed.

Be careful of “diversity” in your existing books that actually reinforces negative stereotypes. “Geronimo Stilton” and “Skippyjon Jones,” as well as anything considered a “classic,” may have visual or written elements that require investigation and discussion. Social Justice Books provides a guide for how to look through illustrations and text to find stereotypes, tokenism, sexism, loaded words and phrases and other embedded cultural norms that might be difficult to identify independently. If you can’t detect it on your own, it is OK. Take time and do some research and self-work. This list from activist and writer Sarah Sophie Flicker and writer Alyssa Klein is a great starting point.

Re-examine the work of well-known authors. Dr. Seuss and Roald Dahl, for example, are beloved authors, but both have infused racism into their work. Dr. Seuss has been criticized for his illustrations of Asians as well as his use of negative Black stereotypes in “The Cat in the Hat.” In “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” Willy Wonka describes Oompa Loompas as happy slaves saved from their previous living conditions by him (a white male).

Check out the color, family structure and stereotypes of animals in picture books. It’s really astounding how many times the protagonist is white, light gray or light brown, and the antagonist, if there is one, is darker. For example, in Max and Ruby, positive characters are white. Babar in Jean de Brunhoff’s books is light gray, while antagonist Lord Rataxes is dark gray. Here are some questions you can use to get your child thinking about these issues. I usually start with a general question such as, “What do you see happening in this picture?” and then follow up with “What do you see that makes you say that?” and “What else can we find?” Some of my favorite animal-based books are the “Mother Bruce” series by Ryan T. Higgins, “A Mother for Choco” by Keiko Kasza and the Bear and Friends series by Karma Wilson.

Review TV shows and movies for bias, tokenism and accents. Before choosing a movie, I check out Common Sense Media reviews or do a general internet search to see what others may have noticed. (For example, searching for “racism in Disney media” will provide an overwhelming number of results.) Once I learn more about the subtle (and not-so-subtle) ways stereotyping and racism are infused in the media, I watch with my children, taking time to pause and discuss it. It takes time and is inconvenient to have these discussions, but raising children who can recognize and speak out against bias and racism is worth it. Check out Embrace Race’s guide to navigating these difficult conversations.

Do some judicious editing. When I do not like how something is presented in a book, I rephrase it, replacing the words or ideas I don’t like with something more positive and inclusive. I do this so often, my daughter is constantly telling me, “Read the right words, Mama!” Many books have good intentions and miss the mark; when they do, fix them. And when I do “read the right words,” I use the opportunity to start a conversation with my child about our family values and why the words or phrases are problematic.

These are the guidelines I use and hope will be helpful to you and your family. But remember: One or two books are not enough to help your children understand the complex issues facing BIPOC. Every time you go to the library, take out a book you might in the past have overlooked. Go to library book sales or your local book store and buy a more diverse selection of books. Use audiobooks when you are in the car; the narration will bring the characters and their experiences alive for your family. Watch a TV show or movie that you might not otherwise have selected. My children have watched “Hidden Figures,” which highlights segregation by showing the reality of separate bathrooms, coffee stations, work spaces and access to books.

It’s powerful for kids to see and hear the history of oppression, exclusion and undervalued work, and not just the current events and emotions that have resulted from those things. As responsible parents, we need to be active in our children’s media consumption and willing to have the uncomfortable but critical conversations to teach them to be anti-racist.