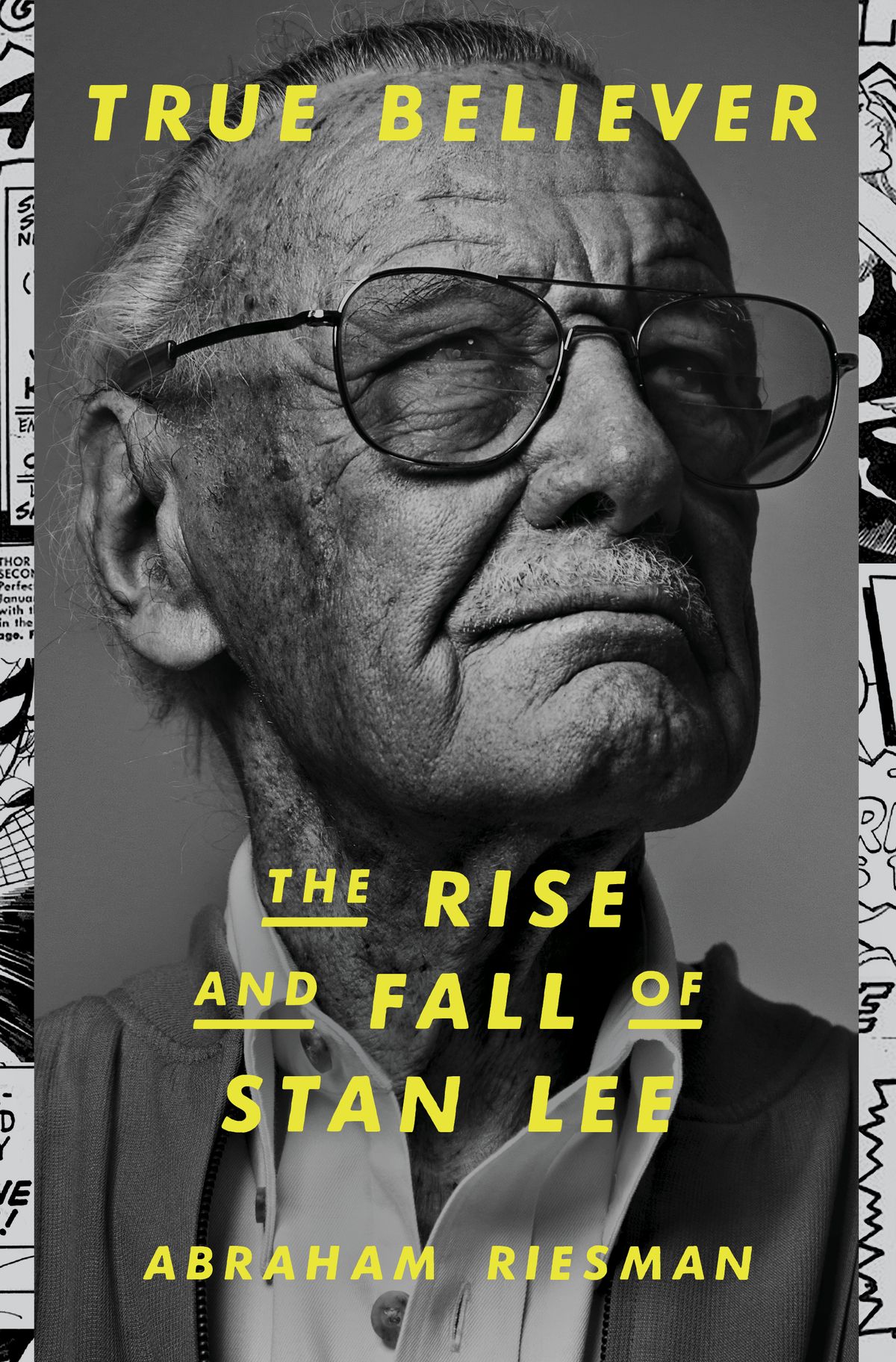

The ‘True’ Stan Lee: Biography grapples with whether he took credit for others’ work

What kind of a person was Stan Lee? You know which way a biography is heading when it opens with a quotation from “Macbeth.”

If you know Stan’s name, it’s likely as Smilin’ Stan, Stan the Man, Marvel’s groovy self-promoting patriarch/editor whose silly appearances in the MCU movies were an in-joke, a living reminder of where the stories started. You couldn’t read an interview with – much less a whole book by – Lee without being reminded that he created that universe, meaning the Avengers, the X-Men, Spider-Man and their many foes.

Alas, that’s not quite true. In “True Believer,” Abraham Riesman shows that Lee, who died in 2018 at 95, most likely took credit for the work of two largely unknown (to the general public, at least) artists, Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko. Lee’s only real five-star accomplishments happened during Kirby and Ditko’s tenures at Marvel, and his futile ambitions to rekindle that flame without them lasted almost 50 increasingly excruciating years.

Riesman tells the story with lively and insightful writing. But he is hindered, as are all historians of comics, by that world’s ephemeral nature. Comics were cheap and disposable, and the business behind them handled like any fly-by-night racket, with little to nothing preserved for posterity. His work is made harder by his subject, who on one hand knew the value of myth and on the other lied constantly. As Riesman says, “Stan Lee’s story is where objective truth goes to die.”

What’s inarguable is that after two decades of a middling editorial career, Lee in the early ’60s was suddenly writing and editing the most electrifying range of superhero stories ever printed. Like Hugh Hefner, Lee was the perfect type of editor for infusing a shabby if not disgraceful medium with new energy, a new audience and a sense of hipness. And comics fit his management style – it’s unlikely Harold Ross would have declaimed from atop a filing cabinet, as Lee reportedly did, “I am God and I want all of you to bow to me!”

He was funny, genuinely friendly and had a great eye for talent and storytelling. He established letters pages to communicate with readers, his side of the discussion bopping with hepcat lingo. Stodgy DC would never have done this. Nor did they grasp what might be Lee’s most important innovation: continuity, meaning stories built on not just previous issues, but on tales that unfolded in other titles. The result was that if you wanted to know why the Fantastic Four were fighting Daredevil, you had to buy all of their previous issues to suss it out. Lee made a clubhouse for millions of lonely kids and made millions of dollars for Marvel in return.

His crowning achievement was how he opened up the imaginations of his collaborators. By use of the “Marvel Method,” Lee would present the germ of an idea rather than a full script, the artist would flesh it out on his own, and then Lee would dialogue it. This was efficient but it also opened a can of worms when the artists weren’t credited – or paid – for their plotting, just their artwork.

To his dying day, Lee claimed the stories and characters were his. Riesman is skeptical. (I, who live for this stuff, was enthralled by his deep-dive, inconclusive analysis of whether Lee or Kirby came up with the Fantastic Four, but won’t assume you’ll feel likewise.) Turns out that unless Lee had a genius artist to transform his germs of ideas into stories, the results were generally forgettable.

There seems to have never been a moment in Lee’s career where he sided with an artist over management. When artist Larry Lieber was desperately looking for work, a staffer dismissed him by saying “the only people Stan thinks about are himself and his family, and that doesn’t include you.” Lieber, I should mention, is Lee’s brother.

Beyond his callousness, Lee remains a little unknowable. Wanting to move on from comics, he wrote bad poetry, lackluster screenplays and egregious-sounding forays into erotica. He had a legendarily disastrous night onstage at Carnegie Hall. It turns out that evening-length shows were not made for Stan Lee; he was best taken, as anyone with Disney Plus can tell you, as a cameo.

By the 1990s, he’d fallen in with grifters who “branded” him with companies whose business models percolated between accidental and overt fraud. Because Riesman had access to some of these lowlifes, the book is a little heavy with awful details of Lee’s twilight years. You get the feeling of the end of Groucho Marx or Salvador Dali here – a maverick in winter, surrounded by con men selling him off for parts.

There’s undoubtedly more to know about Lee and the creation of one of the major forces in American pop culture. This is an excellent dig below the geniality that shows casual fans who he really was. Famously, he wrote, or paraphrased something he heard as: “With great power there must also come great responsibility.” Well, maybe not. As another comics writer says here: “He’s a good guy. He’s just not a great guy.”

Glen David Gold has written comic books for DC and Dark Horse. He is also the author of “Carter Beats the Devil,” “Sunnyside” and “I Will Be Complete.”